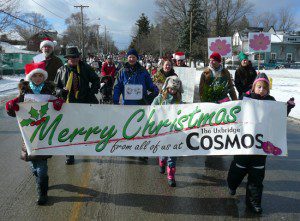

It happened last Saturday morning. We at the Uxbridge Cosmos newspaper had assembled on Maple Street. Our float needed a couple of last-minute touches, but we were ready and waiting for the parade to begin. I was looking for something else to do. I suddenly noticed a traffic jam at Maple and Centre Road. I thought maybe I could lend a hand. When I got there, I found a long line of southbound cars on Centre trying to get through the Santa Claus Parade floats. A woman in the first car I encountered rolled her window down.

“This kid,” she said pointing to her son in the back seat, “has to be at a music lesson downtown in six minutes. Get me through this.”

“Well, try this way,” I said as I directed her along Maple Street.

She followed my hand direction and raced up the street (we both hoped) to get her son to his music lesson on time. For the record, I have no idea whether my direction was a help or a hindrance. I just offered her a potential way out of the psychological and geographical gridlock she faced in that intersection. But I later remarked to my Cosmos colleagues how powerful I’d felt directing her through the traffic.

I’ve never thought of it before, but directing people that way can be an empowering experience, especially if you believe you’re helping people, or, depending on the situation, if you believe you’re preventing people from taking certain routes.

I’ll explain. Just a few hours after my Santa Claus Parade traffic-directing experience, I found myself on the long line-up at Pearson International en route to a U.S. destination. Thus, I was very much at the mercy of U.S. Customs and U.S. Homeland Security people. And they certainly wield a lot of power directing people one way or another.

I mean, the first group in the security process at any international airport are the U.S. Customs people and their minions. They can be the worst. Sometimes, as they push travellers through those zigzag lines en route to an actual Customs agent, they remind me of cattle wranglers prodding animals through livestock chutes at a slaughterhouse. And inevitably those of us in the chutes get somebody who’s just a little too zealous on the job.

“Those with passports must process them at the kiosks,” one woman scolded us, “or you’ll be rejected at the Customs desk.”

Don’t those people wielding all that power in the Customs line-up realize how much damage they’re inflicting on the U.S. tourism industry? Don’t they realize they’re front-line ambassadors either making us feel welcome or the opposite as we non-Americans make our way into their beloved country? Are they perhaps just a bit drunk with power when they start ordering Canadian travellers around like that?

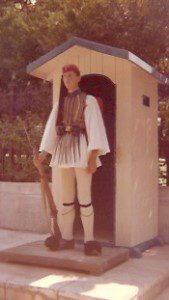

When I was 15, my parents took my sister and me to Europe. We visited England, France, Italy and Greece. There were so many traffic cops at major European intersections – Bobbies in London, Gendarmes in Paris, Evzones in Athens – I was struck by what seemed a colossal lack of traffic signals. Then, my parents pointed out the cops were likely tourist attractions as much as they were practical traffic managers.

Their colourful uniforms, their conductor-like moves, their loud whistles accentuating every direction they dispensed with sweeping arm movements and rapid hand flicks, dazzled us at every busy intersection. I photographed a bunch of them because – as a teenager – I sensed they were important. They were.

The ultimate in the power of traffic direction, however, happened that same trip in 1964 when the family arrived in Athens to visit Greek relatives. One night, my father’s cousin, Pano, took us into the ancient Athenian quarter known as Plaka, where we hoped to find a quiet restaurant to enjoy Greek cuisine and some family conversation.

En route into Plaka, Pano suddenly motioned us on ahead while he attended to a traffic jam in the middle of an intersection. I asked Nana, Pano’s wife, why her husband had suddenly chosen to direct the traffic in the intersection.

“Simple. He’ll tangle up the cars into such a mess,” she said, “that we won’t be bothered by cars in Plaka for hours.”

Meanwhile, back at the Santa Claus Parade, last Saturday, despite my Good Samaritan intentions (helping that woman and her child through the traffic) I knew sooner or later that I would meet my nemesis. It was just a few minutes before the parade began. I was directing the last few cars through the traffic jam among the floats. A guy drove up in a pickup.

“Do you know what you’re doing?” he asked me.

“No,” I shrugged and directed him to follow my hand signals. Fortunately, I never saw either him or the woman rushing her son to music class again. I guess anonymity is what makes directing people and traffic so intoxicating.

Hi Ted, just finished Fire Canoe. I had ordered it before it hit the stores. Loved it! Your historical research and quality of personalizing non animate objects is fascinating reading. I’m not a hard-core reader, but like a meaty story. The steamboats are interesting but not meaty. Personally, (and believe me I’m not an expert) I would have really wanted the great story of the steamboats seen through the eyes and experiences of say a young aboriginal boy that first saw the “Fire Canoes” when they appeared then follow his working life from rivers to lakes to rivers. John