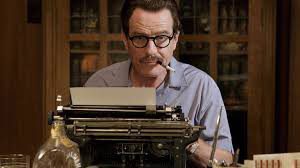

I watched an entertaining and important movie at The Roxy Theatre in Uxbridge this past week. It reminded me of a very scary time in the world. It made me wince at the lunacy of the fear mongering. It saddened me to think that people lost their careers (and in some cases their lives) for their political views in a democratic country … in my lifetime. The hero of the story, Dalton Trumbo, summed it up late in the movie.

“No one on either side (of this feud) who survived it, came through untouched,” he said. “The blacklist was a time of evil.”

Dalton Trumbo wrote for a living. Born and raised in Colorado, he pursued his first public career as a reporter for the Boulder Daily Camera newspaper. At the University of Southern California he reviewed movies, wrote short stories and tried his hand at novels. In the 1930s he was published in the Saturday Evening Post, Vanity Fair and Hollywood Spectator magazines.

An anti-war novel, Johnny Got His Gun, won a National Book Award; interestingly, the novel was inspired by the story Trumbo read about a Canadian soldier who lost his arms and legs in the First World War.

By the early 1940s, was trying his hand at movies, creating the scripts for successful features such as “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo,” “Our Vines Have Tender Grapes” and “Kitty Foyle” (nominated for an Oscar). But he had also joined the Communist Party of America and found himself under FBI investigation. During post-Second World War paranoia about an unsubstantiated communist threat inside the U.S., Trumbo was among 10 Hollywood writers and directors subpoenaed to testify before the U.S. House Committee on Un-American Activities, found guilty of contempt of Congress, and sent to prison. That was Nov. 25, 1947.

After serving 11 months, and itching to write again for his livelihood, Trumbo was blacklisted by what was identified in the movie as The Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals. Hollywood icons such as Ronald Reagan, John Wayne and gossip columnist Hedda Hopper openly campaigned to keep Trumbo and others on the blacklist from ever writing publicly again.

He was forced to write under pseudonyms. Trumbo and many other actors, writers, directors and film tradesmen found themselves listed in a pamphlet, called Red Channels, which identified 151 entertainment industry professionals as “Red Fascists and their sympathizers.” All were barred from employment in the arts. But Trumbo was defiant.

“This blacklisting is going to collapse because it is rotten, immoral and illegal,” Trumbo wrote. “I am one day going to be working openly in the motion picture industry.” And he did. In 1960, both director Otto Preminger and actor Kirk Douglas decided to defy the so-called Alliance and hired Trumbo to script the movies Exodus and Spartacus (respectively) giving him credit with his real name. It was the beginning of the end of the blacklist. But the damage was already done.

Did the famous Hollywood blacklist touch me? Not really. My father, Alex Barris, who almost certainly would have joined the cause of the so-called Hollywood Ten, would almost certainly have found himself blacklisted. But about that time, in 1948, Dad emigrated from New York City to Toronto (to take a job with the Globe and Mail newspaper) maybe because he saw something coming that even Dalton Trumbo didn’t. Trumbo did, however, articulate the consequences of blacklisting.

“Looking back on this time,” he said, according the website bio.com, “it will do no good to search for villains or heroes or saints or devils, because there were none. There were only victims.”

He was right. On a day in that dark 1950s blacklisting era, my father’s Uncle Peter came home to his New York apartment. The way Peter later described it to me, in the lobby he noticed a sign declaring to all who would read it, the names of people and organizations deemed by the House Committee on Un-American Activities as avowed communists, and therefore unwanted citizens and associations. Lo and behold, the name of a photography club, which Uncle Peter had joined in the 1930s, was listed among the hotbeds of communist undesirables.

“I was actually afraid they would discover I’d been a member of that camera club,” Uncle Peter told me, “and throw me out of the country.”

Sarah Palin: American, or … Un-

Fortunately, nobody ever made the connection. My uncle worked without incident until full retirement and lived to a ripe old age in Florida. The blacklist died not a moment too soon. But America has gone on to create new lists of “undesirables”: same-sex partners, according to former Alaska governor Sarah Palin; Mexicans, according to the 21st century Tea Party; and Muslims, according the Donald Trump, now campaigning to become president of the United States.

And suspicion and division will continue to plague such societies until that time, as Trumbo said, “when one man says, ‘No. I won’t.’ Then Rome begins to fear.”