I haven’t been in front of one very often, but as I recall the last time I faced a judge, it was about 10 years ago. I had received a speeding ticket from a Durham Regional Police officer. I was then informed by mail to appear at the Ontario Court of Justice in the Whitby, Ont. That’s where I would enter my plea and face a judge in a courtroom. Of course, there was no jury. No trial either, since I pleaded guilty. Then, the judge looked at me.

“Would the accused please stand?” he asked.

I did. And then he asked me to explain myself.

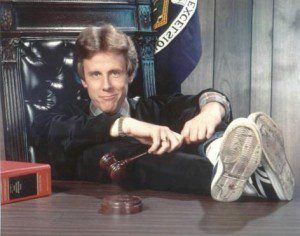

Now, until that moment, about all I really knew about judges and courts was what I’d read in detective novels or seen on TV. In fact, if I had to describe what the courtroom experience was like, I’d probably be limited by the impressions left by actor Larry D. Mann as Judge Lee Oberman in “Hill Street Blues” (in the 1980s) or actor Harry Anderson playing unorthodox Judge Harry T. Stone in “Night Court” (in the early 1990s).

Or, in a pinch, I might think of the former Manhattan family court Judge Judy Sheindlin; I only know about Judge Judy because my neighbour used to have The People’s Court on TV whenever I dropped by for an afternoon chat. And I remember one of her cliché lines:

“On my worst day, I’m smarter than you on your best day.”

I’ve thought about judges quite a lot over the past few weeks: Justice Andrew Goodman in the Tim Bosma murder case, and Justice William Horkins in the Jian Ghomeshi alleged sexual assault case, particularly since Ghomeshi’s lawyers chose to have his trial not in front of a jury, but in front of a judge only. Like many, I guess I wonder about the nature and temperament of judges, how they work, what they see and hear in testimony, and how they assess society’s actions inside and outside the law.

By coincidence this week, in the course of my research of a Second World War military aviation story, I’ve been sorting through the letters of the parents of an RCAF aircrew shot down in 1943. An acquaintance from Tillsonburg, Ont., showed me the contents of a small suitcase containing the letters exchanged among the parents wondering which – if any – of the downed seven-man bomber aircrew might have survived the crash.

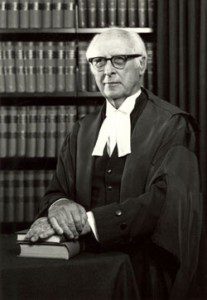

At any rate, as I searched for background of one of the parents, Anne Tomczak (née Hall) of Saskatoon, I discovered that her brother was none other than Emmett Hall, the famous Canadian lawyer and Supreme Court judge. I had the privilege to meet Justice Hall during the production of an interview show, called “The Education of Mike McManus,” on TVO back in 1976.

As the producer of the segment in which interviewer McManus interviewed the then retired Supreme Court Justice, I had to dig through archival material, newspaper and magazine clippings, trial transcripts and law court texts to deliver the essence of Hall in a few short pages.

“Called a dissenter, an architect of social change, and a radical justice, Emmett Hall is also known as a defender of the underprivileged and the oppressed,” I began my report.

I remember learning about some of his extraordinary cases as a Saskatchewan lawyer as far back as the 1920s, when he defended Gerald Dealtry, the editor of a local scandal sheet, The Reporter, when it attacked Ku Klux Klan members who were attempting to rid the province of Saskatchewan of Catholics and Jews claiming, “One flag, one race, one religion, racial purity and moral rectitude.” Hall lost the case, but the court testimony attracted sufficient attention to drive the KKK from the province forever. In 1935, he also defended the “On To Ottawa” trekkers arrested and charged in the Regina riots.

Emmett Hall headed a Royal Commission on education, another on transportation, another on health care and he served the other Prime Minister Trudeau when he wanted an updated assessment of First Nations’ land claims. But perhaps most famously, in 1969, when Emmett Hall sat on the Supreme Court bench, he cast the one dissenting vote in the review of the conviction of Steven Truscott. “I had very strong views that Truscott had not had a fair trial,” Hall told me in an interview. “The whole thing rolled into a ball was a bad trial.” Later that year, Truscott was paroled and in 2008 was awarded $6.5 million for wrongful conviction.

I think when the judge in that traffic court in 2006 asked me to stand up, I imagined that I was facing the likes of Justice Hall. So, when the judge asked me to explain myself, I did exactly what he hoped.

“I shouldn’t have been speeding,” I said, feeling all the embarrassment the judge could have wanted. “It won’t happen again.”