Sometimes, achievement comes in very small packages. And sometimes it arrives when you least expect it. In this case, a friend of mine, a teacher who’s been working diligently to pull together a major event this weekend, was in the middle of something else. Suddenly, one of her students interrupted to show her his latest piece of work.

“He was completely covered in sawdust,” my teacher friend Tish MacDonald said, “and he showed me this wooden silhouette he’d been working on. It was incredible.”

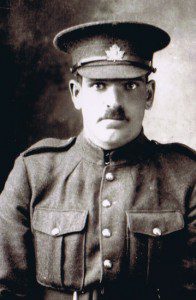

The silhouette is the outline of a soldier, a First World War Canadian soldier, whose figure will join the décor and displays that, in a few days, will transform the local high school in Uxbridge, Ont., into the site of “The Samuel S. Sharpe Gala” fundraiser.

It’s an event that will assist some 54 U.S.S. students – just under a year from now – to travel to the 100th anniversary observances of the famous Battle of Vimy Ridge. But in truth the U.S.S. gala this Saturday will do more than assist the student excursion to Vimy financially. It will also focus the town on one of its unsung heroes, Col. Sam Sharpe, who died the result of mental wounds from The Great War. And perhaps most important of all, festivities this weekend will help the community focus on the innovation and commitment of youth.

Just months before the famous events at Vimy, in April 1917, Gavin McDonald showed the kind of inspiration that Tish MacDonald has witnessed in her modern U.S.S. students. Challenged with the problem of hiding all the chalk dirt he and his crews had excavated while tunnelling their way closer to the German lines atop Vimy, the Saskatchewan farmer and his team of diggers came up with a solution.

“We camouflaged our work,” McDonald wrote in his memoirs, “by getting Canadian machine gunners to fire over our heads as we dumped the excavated chalk into craters (out in no-man’s-land).”

The subterranean battle for Vimy Ridge began as the Canadian Corps (about 100,000 troops), who had never served together as a national entity until then, spent the better part of three months preparing the ground in front of the German Army lines for the planned assault to seize Vimy on Easter Monday 1917.

U.S.S. students, their teachers and their parents began preparations for their trip to Vimy almost as soon as the last group of U.S.S. students returned with rave reviews from the 95th anniversary at Vimy in 2012. Like all high school fundraising efforts they’ve conducted the requisite bake sales, bottle drives and car washes, as well as extra duties at home so that Mom and Dad might help pay their son’s or daughter’s way. But the students have gone all out at the school, manufacturing simulated trenches, displaying artifacts and even assembling profiles of U.S.S. alumni who served in the storied 116th Ontario Country Battalion.

A hundred years ago, another young Canadian had just spent most of the war years saving enough to pay her way to Europe, not to sightsee, but to serve. Turned down by both the British and Canadian Red Cross, when she offered her skills as a driver behind the steering wheel of an ambulance, 20-year-old Grace MacPherson made her way to London, England, and into an audience with the Canadian Minister of Militia Sam Hughes himself.

“I’ve come from Canada to drive an ambulance,” MacPherson announced to Hughes at the Savoy Hotel.

“I’ll stop any woman from going to France,” Hughes said.

Well, conditions at the front superceded Sam Hughes’ resistance to the idea. Presently, he was dismissed and the men driving ambulances suddenly became more valuable in the trenches, and Grace got her wish – loading wounded into her ambulance and ferrying them to hospitals in Etaples on the coast of France.

Like the young students soon to become pilgrims to Vimy in 2017, a century ago, an equally determined farm boy from Wallacetown, Ont., named Ellis Sifton, made his way to Vimy by volunteering, training and serving in the Canadian Corps from the Somme to Ypres and ultimately to Vimy. Writing to his sisters back home, the 25-year-old Sifton confessed his fears.

“I wonder whether courage will be mine, if I am called upon to stare death in the face,” Sifton wrote on the eve of the battle.

Apparently, he did. When his 18th Battalion was suddenly pinned down by a German machine gun early in the battle, Sifton crept into the enemy trench, surprised the gun crew and secured the position, but was shot and killed by a surviving German rifleman. For saving his comrades and advancing the Vimy operation that day, Sifton was awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously.

While none of the Uxbridge youths travelling to the Vimy 100th event next year will have to sacrifice as much as Sifton did in 1917, their journey will no doubt prove to be as life-changing as their destination.