As people often do, a colleague of mine sent me what he considered a joke by email, the other day. I read it and I didn’t laugh. It painted a scenario of an immigrant who, through odd circumstances, had a lot of dependents. Eventually, the man of Arabic background requests assistance from the government. The story concludes with this response:

“I’ve arranged to start mailing cheques … as soon as you arrive in Canada,” signed Justin Trudeau.

I don’t think my colleague wrote this piece himself. It was probably sent to him by somebody else who also thought it was funny. That means that at least two people thought it was funny. I stewed for a long time about replying to my colleague. I finally did. I told him – in so many words – it was inappropriate. And I fully expected a response such as: “Oh, Ted, get a life. Can’t you take a joke?” Well, I’ll try to explain why I can take a joke, that I do have a life … and a conscience.

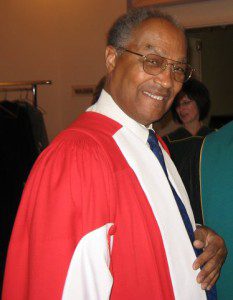

About 15 years ago, I attended the annual Harry Jerome Awards evening. That night a friend and professional colleague, Fil Fraser, received the award “For Excellence in the Professions.” In thanking the Black Business and Professional Association of Toronto for the acknowledgment, Fil commented about being a spokesperson for writers, filmmakers, broadcasters and black Canadians.

“It’s not enough that we believe in equality,” he concluded. “Whenever we see injustice or inequity, we must feel obliged to speak up.”

And in Canada, we have both a good record (saving many of the Boat People), and a bad one (the 19th century Chinese head tax and turning away Jews aboard the St. Louis in 1939) when it comes to speaking up against inappropriateness and injustice. As a historian, I think of the case of Frank Moritsugu, born and raised in Vancouver, editor of his high-school newspaper, before the Second World War. His mom had a piano in the house and she taught him to sing “God Save the King” as a proud Canadian.

At 19, Frank got his first reporting job at The New Canadian, a weekly newspaper published in English and Japanese. In April 1942, federal and B.C. authorities confiscated the Moritsugus’ home in Kitsilano and interned the family at a camp near Revelstoke. Despite being pro-Canadian, The New Canadian continued to publish under heavy censorship by the B.C. and Federal governments. And Frank continued to contribute to the paper.

“The paper pushed co-operation with the evacuation,” Moritsugu said, “which gave (it) room to criticize other things.”

Frank Moritsugu also volunteered for the Canadian Army to go and fight in the Pacific. Finally, at the urging of British and Australian military leaders, the Canadian government relented. In January 1945 it allowed Japanese-Canadian soldiers to go to the Pacific to interrogate Japanese prisoners. Throughout his experience, Frank and his newspaper continued to express concern. When the wartime mayor of Vancouver called for all Japanese to be deported, The New Canadian wrote:

“No matter what the lyrics, Vancouver’s mayor blows a Nazi tune.”

I’ll cite another case of a Dutch-Canadian expressing truth to power, this also from the Second World War. Annie Keijzer had just passed her 18th birthday when her Dutch hometown of Enschede experienced a razzia, when the Germans confiscated radios, precious metals, food and young men for forced-labour camps in Nazi Germany. Annie remembered her father, a hotel operator, taking her to the railway tracks where they watched locomotives pulling cattle cars full of people, mostly Jews, suffocating and crying for help.

She was so incensed by what she saw that she joined the Dutch Underground. At the risk of being shot, she attended a beautician school so that she could bleach Jewish women’s hair blonde to make them appear more Aryan. She then became a courier, delivering news, parcels, and men’s clothing for downed Allied airmen to help them escape to Spain.

Lest I be accused of citing only wartime examples, which I’m sure my detractors would say were extraordinary circumstances, I offer the comments expressed this week by Dr. Brian Williams, the trauma surgeon at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. He operated on some of the officers shot by a sniper on Saturday. Dr. Williams could have sided only with fellow African-Americans. He could have sided with the police, whose lives he tried to save. Instead, he pointed the finger at everybody.

“I understand the anger and the frustration and distrust of law enforcement, but they are not the problem,” he said in Monday’s press conference. “The problem is open discussions about … race relations.”

If we think Canada is immune from such prejudice, such disunity among races and cultures, all we need to do is read what some view as harmless jokes and realize how wrong we are. Like Fil Fraser, Frank Moritsugu, Annie Keijzer and Brian Williams, I believe, “whenever we see injustice or inequity, we must feel obliged to speak up.”