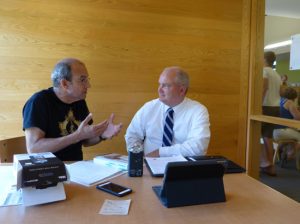

We sat down on a couple of plain chairs at a wooden table. We both splayed reference papers and notes across the table in front of us. The setting could easily have been his or my summer kitchen. Then, after some casual conversation, he hit the start button on a pocket-sized audio recorder in the middle of the table.

“It’s a warm sunny day,” he started. “I’m seated in a reading room in Port Perry Library overlooking Lake Scugog…”

I couldn’t resist. “… And under normal circumstances, we should be down at the lake enjoying the water,” I interrupted.

“But we’re not,” he continued. “This is the inaugural podcast of ‘Durham Past and Present.’”

In my 40-years-plus career as a broadcaster, I’ve worked in front of every conceivable kind of microphone. I’ve sat in hundreds of noise-proof studios. And I’ve had the opportunity to host or contribute to thousands of programs on CBC and private radio. But seated in those library chairs in that tiny reading room for a podcast, last Monday, for me, was a first. MP Erin O’Toole was the instigator. He’d like to give Internet air time to local history from as many corners of Durham Region as possible.

“We’re going to share a story that has fascinated both of us for a number of years now,” O’Toole went on, “Samuel Simpson Sharpe.”

Seconds later, and for about a half an hour, the two of us eased into some of our favourite stories of Sam Sharpe, the remarkable lawyer, turned politician, turned military leader of the 116th (Ontario County) Battalion that he sponsored, recruited and led overseas in the Great War. And while many of the anecdotes you’ve heard or read here before, O’Toole and I discovered from retelling them in that informal setting, that there was something new.

“Sharpe really was shaped by his community,” we agreed.

His perspective as a town solicitor came from his local upbringing at Zephyr. His wish to improve lives in his own neighbourhood was reflected in his decision to run for public office. And his wider view of the world, choosing to serve and encourage others to serve in The Great War, came from his love of nation, province and county. But, O’Toole and I surmised, all those perspectives may have indeed contributed to his undoing – suffering incredible operational injury and ultimately dying by suicide in the final months of the War.

But like the grassroots nature of O’Toole’s idea for the podcast, so much of that Sam Sharpe story – and the tales of others – comes not from lavish docu-dramas or even bestselling creative non-fiction. I learned long ago that Sharpe’s story came from listening to friends, neighbours and keepers of the community keys.

I remember the day, easily 20 years ago, when a member of the local historical society led me into a woods off the Brookdale Road where members of Sharpe’s recently organized 116th Battalion had conducted rifle practice. We even tripped over the humps in the woods, formerly the firing berms where green troops fired their first rounds with Ross rifles at targets a century ago.

“Bet you didn’t know that was in our backyard,” she said.

No. And before I visited another local gem, the former Uxbridge-Scott Museum, I didn’t realize how easily the personality of Sam Sharpe could be explored either. But thanks to then curator Allan McGillivray, I was able to sift through diary materials, newspaper clippings, photographs and personal letters, not online, but right here. Allan showed me one letter that Sharpe wrote to a colleague at the war department; it was particularly illustrative of Sharpe’s fierce Ontario pride.

“I came to Valcartier (Quebec) three weeks ago in response to a wire from the Minister of Militia (Sam Hughes),” Sharpe wrote in 1914. “He made me second-in-command to the Central Ontario Regiment (under) Colonel Watson of Quebec City. … Now he is trying to humiliate me by putting another Quebec officer, who is my junior, in command of an Ontario Regiment.”

It’s a safe bet that Sam Hughes’ treatment of Sharpe and the dissatisfaction shown in this letter to the powers that be, spurred Sharpe to form his own 116th Ontario Regiment in 1916. And all this data came from our community, was saved and catalogued by our local historians, and is displayed by our local museum.

I didn’t have to read watered-down, often erroneous Wikis. I didn’t have to travel to the Western Front in France to get a better sense of the man’s character and commitment (although I have since many times). It was right there in a tangible form, as rich as ever in detail and image, and as handy as our neighbourhood Uxbridge Historical Centre, Museum and Archives.

And, in many ways, that’s what lies behind Erin O’Toole’s podcast project. He’d like to see others – storytellers and story-gatherers – pick up this podcast idea and run with it. I think it would make a unique student-driven initiative to tell our stories to a younger, far-flung, digital audience.