We hadn’t seen each other in awhile. We stopped to catch up. My friend told me it had been a tough summer. His father had passed. He’d had to put a favourite pet down. So, his work as an artist had suffered. We’re about the same age and we talked about whether the idea of stopping work or even retirement had entered his thinking. He pointed out, while it might be appropriate and healthy to slow down or even retire, that it wasn’t feasible.

“I can’t just decide to stop working,” he said. “Working artists can’t afford to do that.”

We talked a while about what retirement might look like for him. He sensed that he might do more work of his own choosing, as opposed to the work that customers needed or wanted done. But ultimately we came back to the kind of work life he experiences.

“Freelance work never stops,” he said.

His comment rang true to me in more ways than one. A few weeks ago, I attended a work session with my colleagues at the college where I teach. The topic was how to explain “precarious work” to our students. In other words, we were asked to strategize about ways to break it to our students in the communications professions, that they may not find regular, wage-paying, staff positions complete with benefits and pensions when they finished school. And, we were asked to discuss just how they might cope with “precarious work.” I asked what our definition of precarious work was.

“Workers who fill permanent job needs, but are denied permanent employee rights,” somebody said. “It generally means unstable employment, lower wages and more dangerous working conditions.”

“Like freelancing,” I said out loud.

The Globe and Mail recently published some statistics on the subject, offering a bit of a sketch of what precarious work looked like in the Greater Toronto Area. According to the story, 44 per cent of adults in the GTA work in jobs that are considered insecure. The study further defined those in precarious work as “people (in) temp agencies, contract workers, freelancers.” And it said the percentage was up from the 2011 figure of 41 per cent. I wondered, as I read the story, how many of those questioned did not consider the work precarious, but indeed a preferred option.

I know a lot of people in the GTA who don’t want to work as staffers for many reasons. Those who are independent handymen, for example, prefer the freedom to choose their jobs and those they work with. They pay, protect and respect the rights of others they hire – plumbers, electricians, drywallers, roofers, painters – the same as any corporation should. However, as far as benefits and pensions, etc., they have to plan and pay for those on their own.

Artists (and I know because before I became a college teacher a few years ago, I had been a freelance writer almost all of my working life) don’t want their creations to be the property of some company or corporation. They want to maintain their copyright and that’s a benefit that comes with freelance status; they want the freedom to be able to create works of their own choosing, not their bosses’ choosing. The freedom, of course, comes with the risk of unemployment, no accident insurance, and a pension only if one prepares for it on one’s own.

“Oh, that’s now called ‘gigging culture,’” one of my teaching colleagues said. “And that’s a whole lot different than precarious work.”

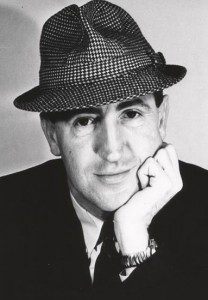

I nodded, but suggested that maybe our role as teachers wasn’t to scare our students into thinking that being independent, well-organized, self-employed professionals was a death sentence. I said I can think of many, including myself, who managed (with assistance from my wife who also freelanced through part of her career) to share the responsibility of a household, pay a mortgage and raise children on a freelance income. And we chose that path. And, by the way, I was taught the concept of freelancing by the best – my father, Alex Barris – who as a writer for print, radio, TV and film, pioneered that sort of work and its related lifestyle.

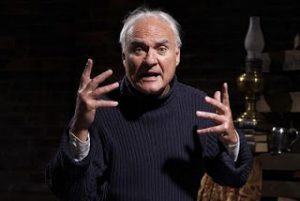

The other night, I attended an event kicking off the Uxbridge Celebration of the Arts. It featured an actor who has worked in film, television and stage for the better part of 50 years. At the Music Hall Saturday night, Kenneth Welsh staged an evening of Shakespearean moments. He gave us bits of Hamlet, Macbeth, Twelfth Night, Merchant of Venice, Henry V from a lifetime of performing on the live stage. Like the artist I mentioned at the outset of my column, Welsh – I’m fairly certain – has worked as freelance actor most of his life. He has worked precariously from the start and, through much hard work, has succeeded.

And while I recognize, as Kenneth has, that such a choice presents tough challenges, I don’t think any of my freelance colleagues would have it any other way. It’s a calling. It’s a risk. It’s a freedom that sometimes money just can’t buy.