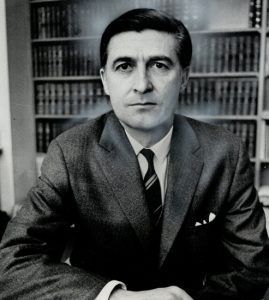

The media came out in droves to hear an important pronouncement about law and the use of a controversial hallucinogenic substance in Canadian society. Then, three sober-looking legal figures proceeded to offer their findings. J. Peter Stein, Heinz Lehmann and the man after whom the report was named, Gerald Le Dain, unveiled their findings.

“The cultivation of cannabis should be subject to the same penalties as trafficking,” Judge Le Dain said, “but it should not be a punishable offence…”

If you thought those pronouncements were a recent dress rehearsal for the current Trudeau Liberal government’s plan to decriminalize the medicinal or recreational use of marijuana next spring, well, you’d almost be right.

In fact, Stein, Lehmann and Le Dain made those recommendations during the time of another Liberal administration, that of Pierre Elliott Trudeau in 1972. After 55 months of exhaustive research, public briefings, deliberations and writing, Le Dain and his two colleagues recommended in their Royal Commission report that cannabis be removed from the federal narcotic control act – decriminalized – and regulated provincially. Yes, that was 44 years ago!

Then, last spring, to fulfil a promise made in the 2015 election campaign, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised to draft regulations with respect to production, distribution, retail and consumption of marijuana. Trudeau made virtually the same pronouncement as Le Dain had.

“We believe in legalization and regulation of marijuana because it protects our kids and keeps money out of the pockets of criminal organizations and street gangs,” Trudeau said.

In other words, it’s taken all that time and another Trudeau administration to reach the same conclusion that Le Dain and his fellow Royal Commissioners did, that decriminalizing possession and drastically reducing charges for trafficking would free up the courts, take control of pot away from organized crime, and prevent the damaging effects of Canadian youth stuck with life-long criminal records for simple pot possession.

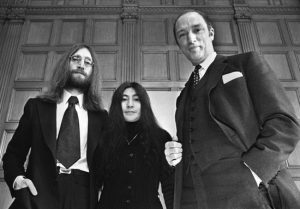

In fact, the Le Dain initiative between 1969 and 1972 attracted the endorsement of former Beatle, John Lennon. As reported by Kate Allen in a Toronto Star story three years ago, several of Le Dain Commission officials sat in a railway car in Montreal, in December 1969, when Lennon praised the Canadian initiative.

“This commission,” Lennon said, “I don’t know what’s going on in the rest of the world … towards drugs, but this seems to be the only one that is trying to find out what it’s about with any kind of sanity.”

Of course, there’s another form of sanity that might help police, judges and politicians regulate the problem – it’s called common sense. I offer one of my own experiences with pot as example. When I was on my own, in my early 20s and freelance writing in Saskatoon, I sought a relatively inexpensive place to live. I found a room in a house occupied by a number of University of Saskatchewan students – in nursing, med school and philosophy, as I recall, on Saskatchewan Crescent. Indeed, the day I chose to move in, the house was raided by the police. It turned out my new cheap apartment was located in the clearing house for soft drugs in the City of Saskatoon.

And I should have seen that as an omen. Some months later, during the late spring, I attended a rock concert at the university, wrote my review of it at our notorious house, and then tripped across the University Bridge to the downtown offices of the Star Phoenix newspaper for edit and publication.

Well, it was such a balmy spring night, that en route back across the bridge, I paused, looked up and witnessed one of the most dazzling displays of Aurora Borealis I’d ever seen. The lights fairly danced across the heavens from North Star to earth and from east horizon to west. I was mesmerized for the better part of 30 minutes. But then it was time to get back to my house – party central – to try to get some sleep.

As I approached the three-story Tudor-style house, I suddenly became aware of loud voices, not inside but outside the house. Everybody – the U of S students and all their pals – were sprawled all over the lawn. Each was nearly obscured by his/her own cloud of pot smoke. And all of them were gazing skyward, their eyes like saucers viewing the same northern lights I’d seen from the bridge.

That’s when the stuff’s potency (or lack of it) suddenly became clear. One of my roommates spotted me coming up the street and ran to me with hand extended to share his joint.

“Man, you’ve got to try this stuff,” he said pointing to the heavens. “You won’t believe what’s going on up there!”

I didn’t have the heart to tell him Aurora Borealis, not THC, was putting on the show. But the incident did illustrate to a certain extent the place of recreational marijuana in Canadian life. I just wish I had presented a brief of my experience to Commissioner Le Dain. I might have been as famous as John Lennon.

Great piece!