My back was to the wall. Eleventh hour. Up against it. All those clichés applied. My Grade 8 history essay – on the causes and effects of the War of 1812 – was due Monday morning. It was Sunday night and the essay was done in every way but one. I pleaded with Dad to help me, not to compose the essay, but to type it for me. And he did, but not without an important provision.

“This is the last time,” he said. “From now on, you’re on your own. You’ve got to type it yourself!”

I nodded, not really understanding what had just happened. All I cared about was that my history paper would be delivered in class, on time and looking spotlessly professional. Why? Because my dad was a professional writer and he would never submit anything short of perfect.

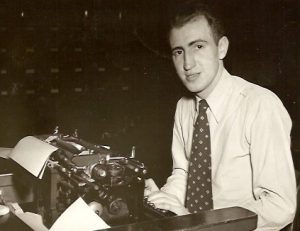

Whether it was a newspaper column for the Toronto Telegram or a script for CBC radio or TV, or one of his many book manuscripts, my dad Alex Barris always delivered copy that was grammatically correct, punctuated perfectly and type-written copy clean. But having agreed to his pre-condition – never to rely on him to type my work again – I had thus dedicated my professional life, as much as I could, to columns, scripts and manuscripts that would be nothing short of Dad’s standard of perfection.

A million things will cross my mind this Sunday, June 18. But among them, when I think of the relevance of so-called Father’s Day, I shall recall such important lessons as that one – accepting responsibility and expecting no higher standard from anyone than one I wasn’t prepared to meet myself. My father was no Ward Cleaver, the fictional father in the quintessential TV sitcom series of the 1950s, “Leave It to Beaver.” In other words, he never professed to have all the answers, nor to be the perfect role model. But my dad had a sharper sense of humour than Theodore Cleaver’s father.

Once, when he, my mother, my sister and I, were on holidays at a summer cottage along Lake Erie, Dad and George Bain (one of his newspaper buddies) visited the local bakery in downtown Port Dover, Ont. As usual on a Saturday, the place was packed with customers, each one taking one of those plastic number cards to be served in order.

Well, when Dad and George were about to leave, and with the store just as busy as the moment they’d walked in, Dad quickly grabbed all the numbered cards, shuffled them all out of order and departed. “We didn’t stay to watch the chaos,” he said; but it must have been as delicious as the bakery’s pastries.

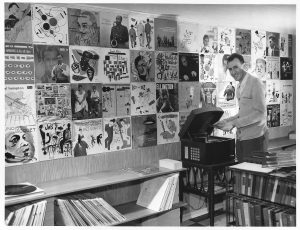

Despite the fact that Dad worked late most nights – covering musical acts at downtown Toronto jazz clubs or the Royal York Hotel and then completing his reviews before the newspaper deadline about midnight – Dad was home as much as possible. And Kay Barris, my mom, was as much the disciplinarian when she had to be; she never used the “Wait ’til your dad gets home” philosophy. Indeed, whenever possible, my father made sure we joined him at the Imperial Room or the clubs for dinner and the shows. When Alex Barris reviewed Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald or Jack Jones, it was often from a table for four.

“Seeing talents like these is an education,” he told me and my sister.

But my father never limited his participation in our family to dinners out. Even though his schedule was all over the map, he rarely missed any of our school recitals, graduations or team games. Among my fondest memories of my dad, were winter Saturday mornings when I played minor hockey.

Even if he’d only had a few hours’ sleep Friday night, Dad managed to attend my house league games – outdoors! I can remember stumbling onto the ice just after 6 a.m., looking to the end of the rink. There was Dad, alone, bundled up, swaying back and forth to stay warm, the cigarette smoke swirling about his parka hood.

“Go, Ted, go!” I could hear him shout through frozen lips.

Years later, when I worked in Edmonton and published my book Positive Power: The Story of the Edmonton Oilers, my Dad happened to be in town. I landed a pair of tickets to see Gretzky, Messier and the rest of those iconic Oilers play Minnesota North Stars (it was Dec. 22, 1982, the night Gretzky actually got into a fight on the ice with Neal Broten). Anyway, I taped the ticket stubs onto the title page of the first book off the presses and gave it to Dad.

“To capture tonight’s magic,” I inscribed in the book, “and as thanks for all a father’s gifts to a thankful son.”

I shared 55 Father’s Days with Dad (he died in 2004). In that precious time, I learned to be thankful, to always find a way to laugh at life, and perhaps most important to be responsible – including for typing my own copy.