I stood in what seemed thunderous chaos. Horses galloped to the right of me, to the left of me. Lances appeared to whisk past my ears. The ground felt as if it were trembling beneath my feet. And I grabbed my dad’s arm, fearing if I didn’t I might topple over. Just audible above the din of the rhythmic panting of the horses and the pounding of their hooves, I could hear singing.

“O Canada. Our home and native land…”

Though I felt as if I were standing alone in the middle of the RCMP’s famous Musical Ride, in fact, there were more than a thousand other people standing side-by-side or in columns separated by railings for a screening of what turned out to be one of the most popular venues, the Telephone Pavilion at the World’s Fair, Expo 67.

My sister, parents and grandparents and I had waited several hours to get in to see the 22-minute film Canada 67 created by Robert Barclay and, yes, Walt Disney Productions. Research reminds me that the Circle-Vision 360-degree film technique, featured 15 gigantic speakers and nine 23-foot-high arched screens surrounding the audience and giving us the “experience of being caught in the action.” But in addition to dazzling my visual and audial senses, the visit went straight to my heart.

It was the summer of 1967. The Leafs had won the Stanley Cup (again) that spring. I was regularly visiting Yorkville to see my favourite bands – Lighthouse, BS&T and Edward Bear. I’d discovered the summer of love. And while I was not yet technically an adult – I had just turned 18 and voting age remained 21 until 1970 – this felt like my moment.

It was actually Canada’s moment, that being the 100th anniversary of Confederation on July 1. But on the verge of graduating from high school, having experienced the cliché exchange trip with a high school in Sainte-Foy, Quebec, I was suddenly swept up in the excitement of Canada’s centennial.

It had all begun earlier that summer. I had taken my first steps into the world of professional radio. My best friend, Ross Perigoe, and I had decided to take the broadcast journalism course at Ryerson that fall, so we were acutely interested in sounds and stories. Then, one morning early that summer, he and I both awoke at my folks’ hobby farm in central Ontario to the sound of a diesel locomotive whistle approaching nearby Pontypool, Ont.

“Daa. Daa. Da-da,” the diesel horn announced. We realized it was the first four notes of the national anthem and we rushed to the station to explore the six-car train that had left Victoria, B.C., six months earlier. On board was an abbreviated history of Canada from pre-history to 1967. It had been our first sensation of Dominion Day fever. And it all seemed to come to a climax when my family and I trekked off to Expo 67 in Montreal to take in the fair. I couldn’t get enough of the Centennial momentum of Montreal, of showing off my high-school French, and that feeling of being Canada proud!

In his book about Canada’s Centennial year, the late Pierre Berton described 1967 as “a great turning point year for Canada. It was the year of the hippies. It was the year of love-ins and sit-ins. It was the year of youth. And this whole change of attitude … changed the look of Canada.”

Expo opened on April 28, 1967; it welcomed 335,000 people that first day, exceeding the 200,000 Expo authorities expected. Two days later, more than half a million came through the turnstiles; on its best day in 1964, the New York World’s Fair counted 447,000 people. And I attended the New York fair then and it couldn’t compare to Expo.

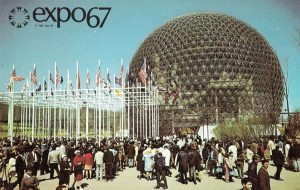

We had the environmentally leading-edge Habitat apartment complex, La Ronde midway rides, Buckminster Fuller’s (U.S. pavilion) geodesic dome, the 3D Union Jack (British) exhibit, the Ontario pavilion with Christopher Chapman’s Oscar-winning film A Place to Stand, the National Film Board’s Labyrinth, and the ultra-modern hydrofoil boats racing around the Montreal islands of the St. Lawrence. Berton summed up his visit to the fair.

“At Expo,” he wrote in 1967: The Last Good Year, “we were all children, wide-eyed, titillated by the shock of the new, scampering from one outrageous pavilion to the next, our spirits lifted by the sense of gaiety, grace and good humour that these memorable structures expressed.”

I felt all of that and more. As I was coming of age, I sensed so was my country. We’d begun to discover the importance of multiculturalism and multilingualism. Our newly minted Charter enshrined rights and freedoms; it remained for us to make it so for women, minorities and indigenous people. Perhaps the best part of being a Canadian during the country’s 100th birthday was that we jettisoned our traditional modesty. The Winnipeg Free Press declared: “No people on earth have been more fortunate; none can look forward to fairer prospects.”

I surely felt that way. Still do.