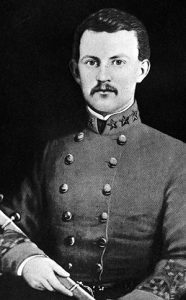

The basics of the story were chiselled into the brass plaque in front of us. It described the heroic advance of a young colonel in the Civil War. More important, beside the plaque, in this little gulley known as Willoughby Run in the middle of Gettysburg National Military Park, one of my dearest historian friends, Paul Van Nest, described the final charge of an officer with the 26th North Carolina Regiment on July 1, 1863.

“His name was Henry King Burgwyn Jr.,” Van Nest said. “He was just 21 years of age, the youngest colonel in the Confederate Army. It was his last charge.”

Van Nest paused a moment. He was overcome by the emotion of describing how this young officer rallied his men in the face of horrific rifle and artillery fire. Despite losing 14 colour bearers, and nearly 75 per cent of the regiment, the North Carolinians pushed the 24th Michigan Regiment back into Gettysburg.

“But Burgwyn was mortally wounded. He died half an hour later,” my friend explained.

There are more than 1,600 monuments like the one near Willoughby Run at Gettysburg. And scores of them depict both Union and Confederate officers on horseback. I thought about my friend’s retelling of Burgwyn’s story four years ago when I joined him on a tour of Gettysburg. I know there’s not a racist bone in historian Van Nest’s body, but he cared enough about the young Confederate colonel’s story, that he shares its humanity every time he leads a tour to Gettysburg. And I thought about the sudden rush to tear down Confederate statues or to remove the name of Canada’s first prime minister from the facades of Ontario schools.

And I think this sudden urge to expunge is missing the point. Tearing down a statue of Robert E. Lee in Baltimore doesn’t erase the enslavement of African-Americans, nor will removing John A. Macdonald’s name from Ontario schools undo the racism of residential schools. Only the teaching and learning from history does that.

I understand that pulling back the curtain on our history – whether the Civil War era or the time of Canada’s Confederation – doesn’t always reveal appropriate events, nor, it turns out, appropriate decision-making by 19th century heroes. Today, nobody will argue that slavery of African-Americans was right. Nor will any Canadian argue today that segregating indigenous young people in institutions was anything but systemic racism.

But hiding the statues behind wooden barriers and whitewashing names from school entryways hardly addresses such mistakes in our past. A nation can reflect on the darker moments in its past without honouring them.

I also think the resolution by the Elementary Teachers Federation of Ontario last week is a little rich. The last time I looked, there was only one mandatory history of Canada course being taught in Ontario schools, and it begins after the Great War, and probably lasts a week or two at most. If we paid more than lip service to Canadian history in our schools – and we lifted it off the page with exciting instruction – we could teach our students why Macdonald’s endorsement of residential schools was wrong and should never happen again. But we could also teach them how the first prime minister ensured that the founding of this country included equality of French and English in religious practice, in education, in court and in society. I think Premier Kathleen Wynne got it right.

“[Macdonald] was far from perfect,” she said. “We need to teach our children the full history of this country.”

As an editorial in the Toronto Star pointed out the other day, when it published its final report in 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission among other things called on governments “to erect monuments in Ottawa and the provincial and territorial capitals to the victims” of that history.

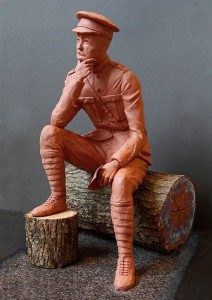

In a way, that’s what Wynn Walters’ sculpture of Col. Sam Sharpe will attempt to do. You’ll notice that the artist’s depiction of the colonel doesn’t place him on a warhorse or leading his 116th Ontario Regiment in a heroic charge. I think Walters’ appropriate intention all along has been to show the man as contemplative, reflective and coping with the trauma that both took his life and excluded him from our Remembrance observances. Here truly is a statue that provokes constructive thought right now and action for the future.

The problem with history that is depicted in one dimension is exactly that. When my historian friend Paul Van Nest described Col. Henry King Burgwyn Jr.’s courage and cause, there at Gettysburg during the sesquicentennial of the battle, I didn’t find myself swept up in the so-called Lost Cause of the Confederacy. I saw a human face of war history. I saw a chance to understand the circumstances. I realized an opportunity for those of us who’ve come along 150 years later to look a little deeper and pass the lessons of past mistakes on to the decision-makers of tomorrow.