When 911 happened, he was working at a magazine in New York. He called it a party magazine. Not particularly substantial. And he was a recognized media critic covering the arts. Suddenly, one morning in September, long-time newspaper reporter David Carr got a call from his editor just after 9 o’clock. The editor told him what had just happened at the World Trade Center and he was assigned to the story.

“Some of the staff are going uptown, some downtown,” the editor told him. “Carr, you go cover the firemen.”

In a conversation I heard years ago with the sometimes controversial columnist and at one time crack cocaine addict, Carr talked about the impact of the 911 World Trade Center assignment. He realized he had never talked to a firefighter before. In a lifetime of professional journalism, including stints at Atlantic and New York magazine as well as the media columnist at the New York Times, he’d researched and written features about pop culture icons, media magnates, and even the underworld. His 2008 memoir “The Night of the Gun” exposed both the drug world and his own addiction, but, it didn’t prepare him for going to the street to get the 911 story.

“What question do I ask a firefighter in 911?” he wondered. “So, your best friend’s dead, how do you feel?”

In an era of 140-character journalism, photo-editing fakery, a media environment so poisoned by public suspicion and distrust, made worse by a U.S. president who considers every piece of reporting and criticism he doesn’t like as, “fake news,” what’s a reporter supposed to do? Well, if you’re a large media outlet, such as Huffington Post, now called Huff Post, you do what capable journalists have always done. Starting this month a travelling party of rotating HuffPost staff members will visit more than 20 cities across the United States. Why?

“Trust in media has bottomed out,” the HuffPost website says. “We hope to rebuild some of that, and to learn from it, by listening to the public and evaluating their stories through our massive distribution network.”

A.K.A. gumshoe journalism. They’re reverting to where reporting came from when reporters used steno pads and pencils, wore fedoras and trench coats, and asked the basic Five-W questions – Who? What? Where? When? And why? Having taught countless students at Centennial College over 18 years about such things, and now reflecting on it as a recent retiree, I still happen to believe that’s the way you get to the truth. Let me offer a personal example of what I mean.

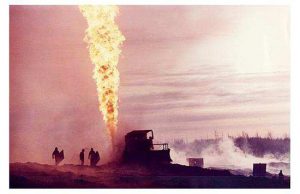

Back in October 1982, a gas well that was owned and operated by the U.S. oil company Amoco, southwest of Edmonton, experienced a blowout. People near the well (outside Lodgepole, Alta.) were relocated. The area was cordoned off. And nobody – least of all reporters – was allowed any access to the well site. CBC Radio wanted the story covered. I offered my services. When I got to the town, I searched out an Amoco public relations officer.

“There’s no danger to the public,” she said. “Everything’s under control. And we have a contingency if anything happens.” And she ended the interview there.

At the municipal office, I approached the town administrator. “There’s no danger to the public,” he said. “Everything’s under control. And we have a contingency if anything happens.” And he took no further questions.

When I got to the local RCMP detachment, you can guess what answer I got from the officer in charge. Ditto.

I was beginning to think I was trapped in an episode of “Twilight Zone.” I was worried I’d have nothing for my radio report. Then I bumped into two air-quality monitoring crewmen from the Alberta environment department. They allowed me to record their air pollution readings, which indicated the sour gas escaping from the well was powerful enough to turn house exteriors yellow and too toxic for humans within several kilometres.

However, my real breakthrough occurred when I ambushed a mud-compacting crew, recently arrived from the West Coast. They had seen the site, but hadn’t been told by the oil company what to say. They were about to check into a motel I’d staked out and I asked them to describe the well site. “It’s a mess,” one of the crewmen said. “Like a lunar wasteland.” And I had my story.

My point is, that I could have relied on the Internet and social media to take me to the blowout story. But I figured I owed it to my listeners to find out myself.

I should finish by pointing out what David Carr learned on Sept. 11, 2001. At one point as he stumbled among bewildered New Yorkers, including the firefighters, he suddenly stopped and asked a stranger what he thought the 911 story was.

“It’s about those who have and those who want,” the person said. Carr (who died in 2015) would never have found that kind of an answer at a computer screen or on a cell phone. The truth was out there on the street.

After having just watched “Page One: Inside the New York Times” in my resumed Reporting 3 course at Centennial College, I can say that David Carr is indeed respected. What is clear in this documentary, is that Carr works extremely hard to get not only the facts, but the necessary details that go along with the facts. He is another reporter that students, like myself, could learn a lot from. It is a shame that he has since died (in 2015), but his legacy lives on in documentaries and stories used in Journalism programs across the world.

I hope that retirement is treating you well, Ted.

Joe