The padre stepped up to the lectern this past Sunday morning in Shedden, Ont. The audience at the community centre for the Remembrance service settled into silence. The clergyman unfolded his papers, that I thought would contain a prayer, a piece of scripture or perhaps the words of a hymn. But, no, he looked out at the assembly of cadets, veterans and the public in the audience and introduced his Nov. 11 thoughts this way.

“From simple actions, come astonishing results,” he said.

Rev. John Brown has presided at the annual Remembrance event at in Southwold Township, southwest of London, for a number of years. But since one of the themes of this year’s service, in which I participated, was the 100th anniversary of the battle at Vimy Ridge, Rev. Brown chose to tell not a story of death and destruction, but of hope and rebirth. He quoted the diaries of a Canadian signal corpsman, Leslie Miller, who served at Vimy between April 9 and 12, 1917. Miller referred to the battlefield as “by far the worst sight I have ever seen.”

However, the 28-year-old soldier survived and as he departed the ridge, he collected a few acorns from the ground where the majestic oaks had been shattered by the four-day battle, and mailed the oak seeds home to the family’s fruit farm near today’s Toronto suburb of Scarborough. Essie Miller, Leslie’s wife, planted the acorns and named their farm “Vimy Oaks.” Ninety years later, the son of a Canadian veteran of the Second World War, Monty McDonald who knew about the Miller acorn planting, visited Vimy Ridge in France.

“I didn’t see a single oak tree (there,)” Brown quoted McDonald in the story, “and I thought why not plant a few acorns from (Miller’s) Scarborough woodlot?”

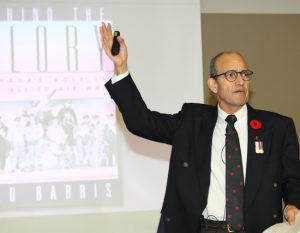

When it was my turn to speak at the Shedden Remembrance event, I complimented Rev. Brown on his theme, “from simple actions come astonishing results.” And I addressed the audience about a little-known aspect of Canada’s contribution during the Second World War, the training of airmen at 230 different military aviation schools across Canada and about the virtually invisible instructors whose simple actions had delivered astonishing results.

When WWII began, it was clear that qualified pilots, navigators, wireless operators, flight engineers, gunners and ground crew would be in great demand. The prime ministers of Britain, New Zealand, Australia and Canada decided to have all those trades trained here in Canada. The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) was born. The Plan taught 225,000 airmen those skills.

But nearly lost in the rush to get those airmen trained and overseas were the trainers themselves, about 5,000 instructors who were told, “No, you’re not going into combat. You’re so good at your skills, you’ll teach others.” One such airman was Ontario cadet Tom Hawkins. Leading Aircraftman Hawkins had excelled at math in school, got through initial training, but barely made it through elementary pilot training.

Then, in 1942, he was asked to fly a twin-engine Anson aircraft from Brantford to Toronto Island. En route, Hawkins discovered the Anson had lost its air compression. He had no brakes! And yet he managed to bring the plane to a full stop by stalling and slowing the airplane to a hald before it went into Toronto Harbour.

His miraculous skill made him an ideal instructor, and he taught hundreds of other pilots, from 1942 to 1945, never getting where he really wanted to go, into Spitfires and Hurricane fighters over occupied Europe. He also came to realize he would get no official recognition – ribbons, medals and citations – for his BCATP service. But he described why he was the best at what he did.

“In instructing,” Hawkins said, “you had to let the student (pilot) go as far as possible to recognize he was doing something wrong. You had to let him go so he could learn. Then, if he didn’t recognize his mistake, you had to take over before things really went wrong. No one can teach you that. You learn by experience.”

For instructor Tom Hawkins, the reward for his RCAF service was simply the sense of lessons learned, pilots taught to the highest standard possible, and the satisfaction at the end of the war of a job well done. And it proved to be so. Hawkins was never recognized for his simple actions, although their astonishing results were acknowledged by Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who called the men who instructed in the BCATP, “the decisive factor” in winning WWII.

By the way, just to illustrate how remarkable Rev. Brown’s story about the Vimy Oaks has become, the acorns that Great War soldier Leslie Miller planted in Scarborough in 1919 have themselves – 100 years later – yielded giant oaks and acorns. And those seeds in turn are growing at a nursery in France to be re-introduced on Vimy Ridge next spring. And others of those Vimy Oaks offspring have made their way across Canada, including nearby Uxbridge Secondary School this Friday at 1:30 p.m.

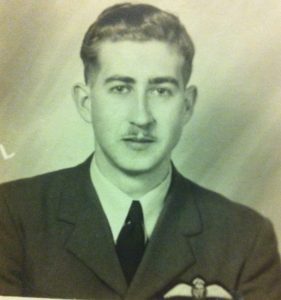

My Dad, an RAF Mosquito pilot, was one of those airmen trained out west. After earning his wings, he was stationed at Mount Hope airbase, where he flew the planes used to train “navvies”. Meeting my Mom at church in Hamilton led to love and eventual marriage after the war. Eventually, he was posted to Epinoy France, flying bombing missions. He used to say his crew was international… a Welsh pilot with a French Canadian navigator on a British plane in a Polish air squadron!