Several years into the Second World War, a young teacher in a small Czechoslovak town made a decision. It nearly cost him his life. Oldrich Patrovsky, who taught primary grades so he could support his family, in 1942, watched Jewish neighbours uprooted and transported away. He chose to help some of them escape the Nazi dragnet. He was arrested and incarcerated inside the 18th century military fortress at Terezin. It’s a place in the former Czechoslovakia that the Nazis had transformed into a prison for political prisoners and a transit camp to redirect Jewish prisoners to death camps in Eastern Europe.

“His crime was being ‘a friend of Jews,’” Patrovsky’s great-granddaughter told me this week.

I met Veronika Shavikova at the Terezin historical fortress while touring there with travellers from Canada. Born long after the war, she described her great-grandfather’s fate. “He was held there for 10 months,” where in some cells (built for 10 or 12 men) up to 75 prisoners were forced to sleep standing up. “Some of them died of the exhaustion,” she said.

While not a life-and-death decision like Oldrich Patrovsky’s impulse to help his Jewish neighbours, Veronika Shavikova has had to make a critical choice in her own life too. And she’s made it in the same town where her great-grandfather was imprisoned in 1942-43. When Soviet control of Eastern Europe ended in 1989, the small Czech town of Terezin tried to survive by establishing a series of Holocaust sites and museums while attempting to attract students to a planned university.

Then, catastrophic floods hit the region in 2002, and funds designated for the university had to be redirected to rebuild the town. The fortress’s historians and staff had to preserve Terezin’s wartime story unassisted, or see their town shrink and die.

“I was trained as a landscape architect,” Shavikova said, “but my husband and I believe this town and its history have potential. It’s unique.”

Interpreting much the same Holocaust history across the border in Poland, Krzysztof Jasinski guides English-speaking tourists past the famous “Arbeit macht frei” (Work makes you free) sign over the entrance to Auschwitz concentration camp, as many as 14 times a week. Over 11 years, that means Krzysztof has shown many of the more than 2 million who tour Auschwitz every year the horror beyond the sign.

The day of our visit, he showed us some of the 43,000 pairs of shoes the Nazis accumulated from the Jews they killed, the shaved hair they made into textiles for army uniforms, the kilograms of gold they harvested from the bodies. And there’s a sickening irony for his audience.

“The place where the Nazis stored all their plunder was sarcastically called the ‘Canada warehouse,’ (a place they considered prosperous,)” he said. “It was organized robbery in a factory of death.”

I learned from Krzysztof that he has a master’s degree in the history of Polish literature, and a master’s in Polish philology. And he hopes to move to North America one day to pursue another of his passions – game design. I asked him what he thinks of his 11 years immersed in recounting the details of the Auschwitz atrocities 500 times a year.

“I don’t know yet,” he said. “But I believe the work is important.”

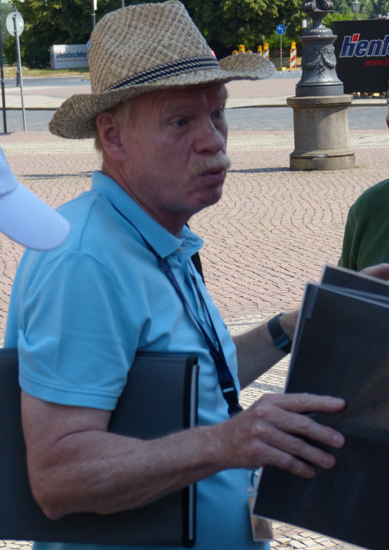

It’s the post-Second World War era that has kept Günter Kieb rooted and gainfully employed by the history of his hometown. When Allied commanders and political leaders divided Germany after the war into East and West Germany, they consequently left the city known as “the Florence of the Elbe” isolated in the eastern Soviet Bloc.

“The Russians stripped Dresden of everything – steel, wood, wire – anything that would have helped us rebuild,” Günter said.

And as he grew up, through the 1950s and ’60s, Günter despaired that Soviet reconstruction provided some housing but restored little of the art, culture, and infrastructure that would have returned Dresden to its former glory days.

Nor did Soviet administration allow for freedom of movement until students, teachers and workers challenged the East German regime in 1989. There were demonstrations demanding that Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev grant the same freedoms that existed in the West.

“Three thousand protestors went to the streets on the eighth of October and within a year the (Berlin) Wall had fallen,” Günter Kieb said, and little by little his beloved Dresden began to rebuild itself, by itself.

The history of Europe is not only that of shooting wars and cold wars. Nor is it solely about the oppression of races, languages, religions and political movements. But for those of us who’ve lived in relative peace half a world away, Europe’s 20thcentury of conflict identify the pitfalls of hatred to avoid.

And it is contemporary European interpreters, such as Veronika Shavikova in Terezin, Krzysztof Jasinski in Auschwitz and Günter Kieb in Dresden, who’ve taken years of their lives and pages of their own history, to consider the alternatives.

“I do this to honour my grandfather,” Veronica Shavikova said, “and so others can learn.”