I think it was sometime last winter when one of my hockey buddies and I got talking about one of my favourite topics – history and history-making. He knew that I’ve always been curious to check out different, off-the-beaten-path stories. Suddenly, the latest one on his mind came to him and he blurted out the gist of it.

“Did you see the latest World War II story?” he asked. “They found a U-boat up the Niagara River near the Falls.”

I thought about it for a second, then said quietly, “I’ll bet you read that on the internet.”

“Yup. And there were pictures,” he added for verification.

“You realize there was no St. Lawrence Seaway back then, don’t you?”

“Right,” he said as the light went on, and added, “Fake news…”

The invention of fake images and sounds is nothing new. It’s just that at its origin, the practice of imitating reality was restricted to novels, radio dramas and computer-generated images at the movies – a.k.a. entertainment. Even in 1938, when Orson Welles produced a radio drama mimicking a Martian invasion of Earth, he knew enough to offer a disclaimer at the beginning of the Sunday night program heard across North America.

“The Columbia Broadcasting System and its affiliated stations,” the announcer said to open the program, “present Orson Welles and the Mercury Theatre on the Air, in The War of the Worlds, by H.G. Wells…”

Nevertheless, by 9 o’clock that night – Oct. 30, 1938 – people in New York were panicking in the streets, calling police, and genuinely fearful that the world was ending.

Back then they called it a hoax. Today, Welles’ pre-Halloween joke would be considered child’s play. In 2018, fakery has crept into high-end fashion, (of course) entertainment, professional sports, political satire, and hourly/daily news coverage in the media. And I’m not talking about The National Enquirer here; we’ve gone way beyond two-headed babies, extra-terrestrials visiting Hollywood stars, or political trysts.

What began as U.S. President Donald Trump’s defence against alleged ruthless business practices, sexual abuse of women, and collusion with the Russians in his 2016 election win, this week, escalated to international misrepresentation. First, following his Helsinki summit with President Vladimir Putin, Trump said he had no reason to believe tampering “would” involve the Russians. Then, when he realized everybody back home – opposition Democrats, governing Republicans, and his own intelligence advisors – were foaming at the mouth, he said he’d meant to say there’s no reason to believe the Russians “wouldn’t” be involved.

What began as U.S. President Donald Trump’s defence against alleged ruthless business practices, sexual abuse of women, and collusion with the Russians in his 2016 election win, this week, escalated to international misrepresentation. First, following his Helsinki summit with President Vladimir Putin, Trump said he had no reason to believe tampering “would” involve the Russians. Then, when he realized everybody back home – opposition Democrats, governing Republicans, and his own intelligence advisors – were foaming at the mouth, he said he’d meant to say there’s no reason to believe the Russians “wouldn’t” be involved.

Whether you believe President Trump is inventing memories of the summit, or that the international media are, almost doesn’t matter anymore. Things have reached such an extreme in news coverage that the mere mention of a mistake, a miscue, a slur, or a political misspeak by a public business, entertainment or political figure usually elicits the last-ditch “fake news” outburst as an irrefutable defence.

“The summit with Russia was a great success,” the president tweeted proudly, “except with the real enemy of the people, the Fake News Media.”

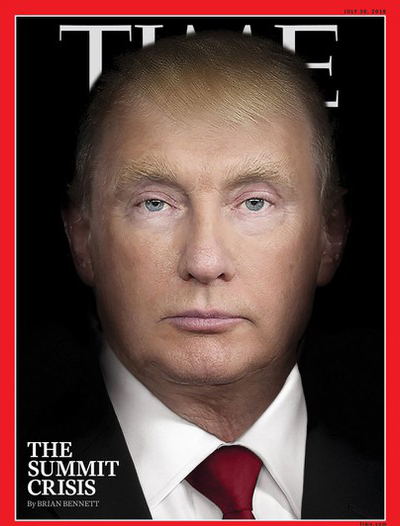

Then, just when you thought distrust, misrepresentation and fakery couldn’t get any worse, this past week, Time magazine published a front cover showing a morphed image of Trump and Putin. The hair is Putin’s. Aspects of the eyes are Putin’s. But the nose and mouth are Trumpian. And the neck and tie too. Explained Time reporter, Brian Bennett, in his cover piece, “Trump wanted a summit with Putin. He got way more than he bargained for.” Adds artist Nancy Burson, who created the image, she wanted to illustrate the shifting appearances of the two leaders. All of which is fascinating, but further fuels the fakery that media, public figures and the public have resorted to.

Then, just when you thought distrust, misrepresentation and fakery couldn’t get any worse, this past week, Time magazine published a front cover showing a morphed image of Trump and Putin. The hair is Putin’s. Aspects of the eyes are Putin’s. But the nose and mouth are Trumpian. And the neck and tie too. Explained Time reporter, Brian Bennett, in his cover piece, “Trump wanted a summit with Putin. He got way more than he bargained for.” Adds artist Nancy Burson, who created the image, she wanted to illustrate the shifting appearances of the two leaders. All of which is fascinating, but further fuels the fakery that media, public figures and the public have resorted to.

Enter “Deep Fake.” Not so long ago, artificial intelligence geeks came up with something they called “auto-encoder neural architecture,” a fancy way of encoding a photograph of one person and integrating that data with the code of another. Eventually somebody hatched the idea of introducing the face of actor Nick Cage into well-known movies in which he never appeared. Naturally, the technology became available to the public, and now anybody – even your kids – can morph everybody into anybody.

But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Not so long ago, Hudson Hongo, the culture editor of the online magazine Gizmodo, wrote a short story “The Shocking Assassination of President Guy Fieri,” in which fake videos become commonplace and evolve into, well, the title explains it. And we all thought that the movie Forest Gump pushed invented photo-imagery to the extreme by plunking Tom Hanks into scenes with John F. Kennedy, ping-pong diplomacy and the Watergate scandal.

Where once editors fact-checked or critics posed devil’s advocate questions to learn the truth, and those in the public eye felt compelled to answer for their actions, now everyone can dismiss criticism as lies, or quite simply reshape their version of the truth until it’s blurred into irrelevance.