I drove into the museum parking lot last Saturday morning. Leaning over the tailgate of the pickup parked next to me, several guys in ball caps and jeans surveyed their precious cargo. I peered into the back box of the pickup, but I couldn’t recognize the rusty tangle of metal and wires as anything I’d ever seen before.

“Can you believe it?” one of the guys said. “We salvaged it from a ditch just this morning.”

This was Nanton, Alberta, a town of about 2,000 people, south of Calgary. But as small as this place was, it seemed as if the world had gathered there last weekend. You see, Nanton is home to the Bomber Command Museum of Canada, one of only two museums commemorating the airmen and women of Bomber Command in Canada.

In the Second World War, when Nazi Germany threatened the very existence of Britain, the Royal Air Force called on its military aviators, and thousands more from around the Commonwealth, to take the war to its enemies. Under Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, Bomber Command often put a thousand aircraft per night in the air against Nazi targets. More than 55,000 aircrew died in those actions, 10,000 of them Canadians.

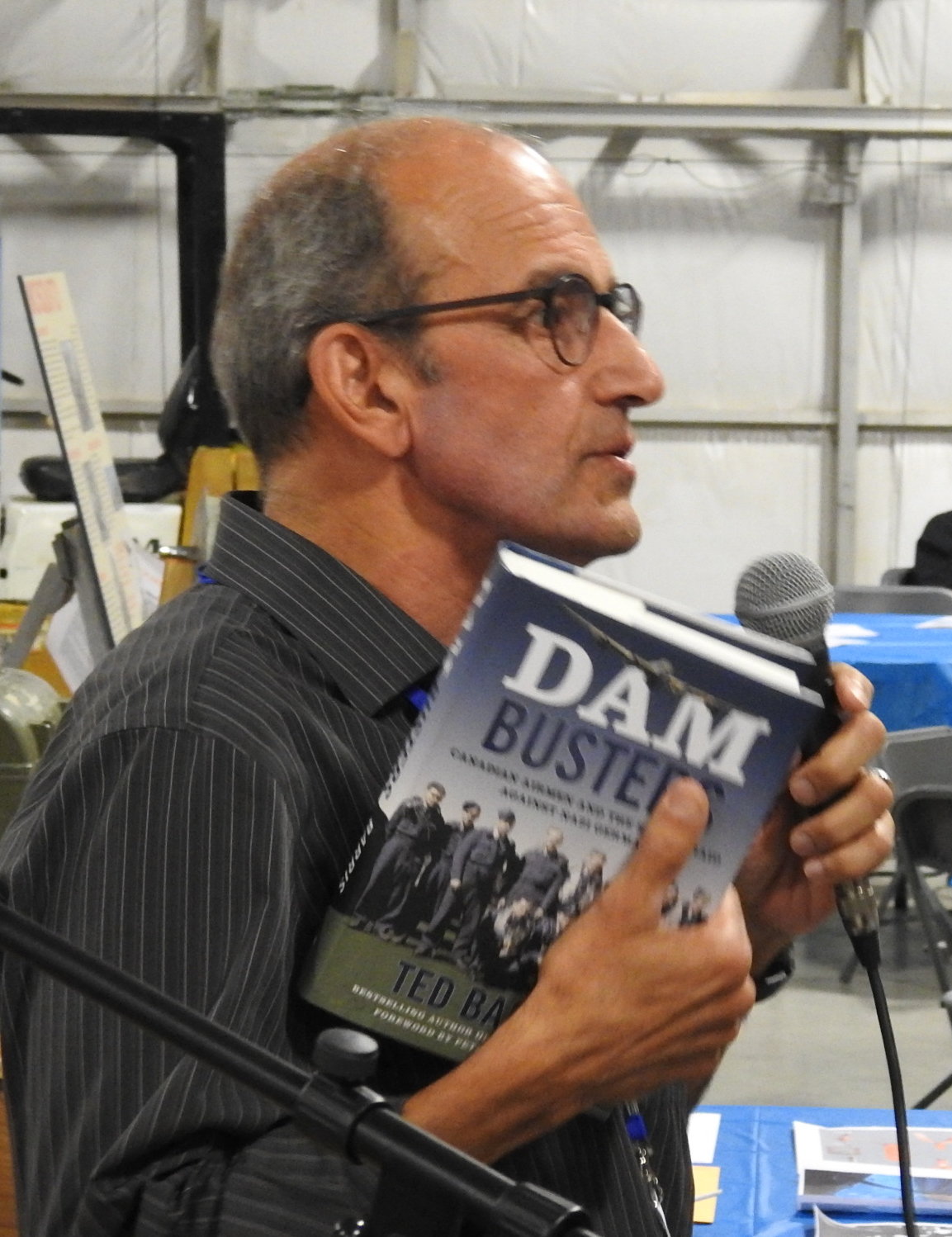

This past weekend, I was asked to speak at ceremonies recognizing the 75th anniversary of the famous Dam Buster raid of May 1943, when Lancaster bombers attacked the hydro-electric dams of the Ruhr River to reduce production of war munitions in Nazi Germany. The commemoration attracted hundreds of history buffs, aviation enthusiasts, some dignitaries, and the people I often describe as “rivet counters.”

This past weekend, I was asked to speak at ceremonies recognizing the 75th anniversary of the famous Dam Buster raid of May 1943, when Lancaster bombers attacked the hydro-electric dams of the Ruhr River to reduce production of war munitions in Nazi Germany. The commemoration attracted hundreds of history buffs, aviation enthusiasts, some dignitaries, and the people I often describe as “rivet counters.”

You know them. They are aficionados, truly experts, on their chosen subjects, in this case all aspects of military aviation – from aero-mechanical specs of air engines to the aero-dynamics of air frames, from the destructive capacity of bomb payloads to the calibres of their gun turrets, and from the histories of every bomber squadron to the number of sorties (missions) accumulated by their decorated squadron leaders.

If it seems like minutia, it is. But every rivet counter I know is proud of his/her knowledge, and equally important, doesn’t hesitate to correct you if you misrepresent their domain.

For example, in all of my research on this dams raid story, I had learned that the attacking air speed of the Lancaster bombers – like the one you occasionally see flying from the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum in Hamilton – was about 235 miles per hour. And especially when the bombers on the Ruhr River dams raid needed to reach that precise speed to deliver the bouncing bomb to the target that night, I wanted to be sure. One of my aforementioned experts, suggested I got the speed wrong.

“Couldn’t have been that high,” he said.

“I think the manufacturer’s manuals listed that speed,” I said.

“Well, OK,” he relented. “But it still seems a bit fast.”

One thing I’ve learned when dealing with rivet counters is that you never respond to their assuredness with equal force. Notice that I said, “I think,” suggesting there was room for error on my part, not his. I do that in part because while aficionados sometimes seem obsessive and intrusive, they can also be valuable.

I’ve written a dozen long-form works on military history. I have no academic standing in the field. I just interview, research and explore as far and wide as I can. In short, I do a lot of listening. Consequently, when I’ve finished writing the book, I often ask an expert – a rivet counter – to check the context of my stories. And they can get pretty snarky when they catch a mistake. Here’s an example:

“You’re going to slap your forehead for this, but the 4,000 pound (bomb) was not a high-explosive HE bomb, but a high-capacity HC bomb,” he wrote. “Two different things!”

Who was I to argue? I changed it to HC, as I changed anything else he questioned, unless I had pretty powerful evidence otherwise.

Meanwhile, those guys with the pickup truck in Alberta. They call themselves the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) group on Facebook, a.k.a. rivet counters. They had just returned from a morning trip from Nanton to a nearby airfield at Vulcan that had trained pilots in WWII, with their truck full of this stuff.

“What you see here,” explained Peter Whitfield, one of the BCATP group, “are the remains of the engine and landing gear mount for a Mark 1 or 2 Avro Anson.” And he pointed to shreds of rusted steel and frame from a plane that had flown in the skies over Alberta over 70 years ago. “After the war, it was bulldozed into a ditch. We recovered it this morning for the museum.”

“Why?” I asked innocently.

“Have to preserve it,” Whitfield said.

“It shouldn’t be rotting in a ditch,” said his pal Ken Meintzer. “It should be on display for people to understand their history.”

Got to love those rivet counters.

The Imperial War Museum, which is full of rivet counters, too, says that the Lancasters’ speed on approach to the dams was 232 mph, but that was to be their ground speed, not their airspeed.