In one of the first notations he jotted into his combat journal, First World War soldier Sam Sharpe recorded the actions of his rookie Canadian battalion. The 116thOntario Country Regiment was experiencing its baptism of fire in France. It was April 9, 1917, the first day of the battle of Vimy Ridge. His men were not fighting German soldiers, but laying wire in communication trenches on the Allied side of the Western Front. L/Col. Sharpe noted that his men endured a hail of artillery shells as they worked. Members of the 116th were wounded or killed, including one of his closest friends in the battalion.

“It is awfully sad,” Sharpe wrote. “Lt. John Doble was killed instantly by a shell, while leading a wiring platoon. Ontario County is paying its toll in this great struggle.”

This Sunday – for the 100thtime – at the 11thhour of the 11thday of the 11thmonth – we will gather at the cenotaph at Brock and Toronto streets in Uxbridge. We will observe a century of Remembrance Days acknowledging the service of Canadian warriors and peacemakers. We will pay tribute to Doble and scores of others who left their homes in the service of their King and country 100 years ago. We’ll mark the loss of those individuals in what was supposed to be the war to end all wars.

In total, the Great War would take the lives of more than 60,000 Canadians. In number, the loss would prove to be an even greater Canadian sacrifice than the Second World War, in which 41,000 Canadians lost their lives. In so many ways, the thousands of casualties at Vimy, combined with those at Ypres, the Somme, Passchendaele and the rest, would leave more than individual families grieving. The effects of a generation lost to warfare between 1914 and 1918 would change homes, neighbourhoods – entire communities.

Harry Loosmore, for example, had witnessed the trials of the 4thDivision at Vimy Ridge from the relative safety of the 44th Battery gun pit in front of La Folie wood. Loosmore had enlisted in the artillery in Victoria, B.C., in 1915. In training at Bramshott, in England, army authorities spotted his abilities as a blacksmith, so they posted the 24-year-old volunteer to the 44th as a shoeing smith.

On April 9 during this crucial attack which would end in victory for the Canadians, Loosmore watched incoming stretcher bearers with Canadian wounded and dead. In my research of the Vimy story, I found Loosmore’s diary in which he lamented not only about the friends lost that day, but also about the impact their deaths would have on their home community in British Columbia.

“Salt Spring Island paid a high price for her share in the Ridge,” Loosmore wrote. “The two Lumley brothers of Fulford were killed by the same shell. Henry Emerson, who operated Mouat’s Feed Store, went too – I can still see him practising ball catching with Arthur Drake on Ganges Wharf in the summer of 1915. Donald Craig, aged 20 … and Charlie Dean … who acted like a big brother to me … died of wounds and was buried in Barlin extension cemetery.”

The toll the Great War took on the rest of Sam Sharpe’s 116th Battalion became clear, especially during last spring’s unveiling of Wynn Walters’ sculpture in downtown Uxbridge. The first seven months of its service on the Western Front had killed or put out of action nearly a third of the battalion’s strength. By late 1917, the 116thhad been reduced to only three fighting companies, about 270 men. And Passchendaele proved the last straw for L/Col. Sharpe.

“We have very little protection and I may not pull through,” he wrote his wife Mabel Sharpe. “If it should be my fate to be among those who fall, I wish to say I have no regrets…” We know barely seven months later, shipped home and suffering from “shell shock and complete physical and mental exhaustion,” that Sam Sharpe took his life and came home to Uxbridge in a casket.

The community would never know what contributions the man might have made back in civilian life as a lawyer and back in the House of Commons as an active and popular MP. Such was the loss of a generation to the Great War.

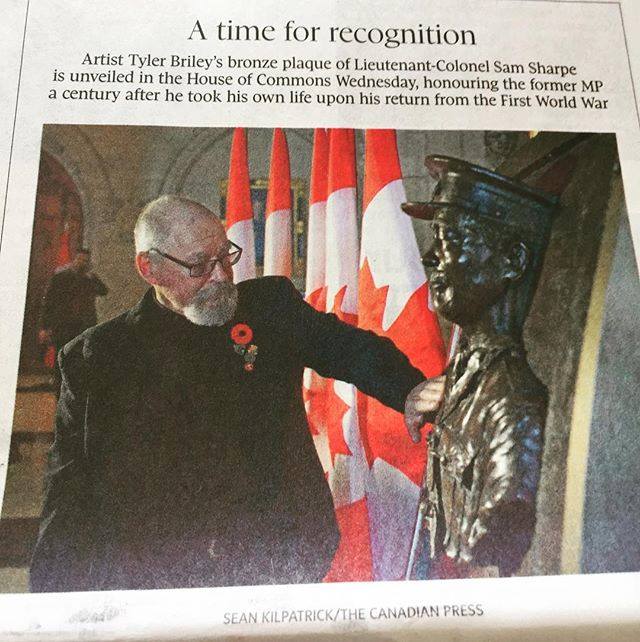

However, with the 100th Remembrance Day just days away, we’ve learned there is some salvation. This week Seamus O’Regan, the minister of Veterans Affairs, formally began the process of recognizing L/Col. Sam Sharpe’s death from mental stress as a war wound, and announced that the sculpted relief fashioned by artist Tyler Briley would be – at long last – installed in Centre Block. For at least one forgotten casualty of the Great War there would be the restoration of reputation and the appropriate honouring of a volunteer, citizen, MP and soldier of the Great War on the eve of the 100th Armistice.