It was getting late. I’d been interviewing him for several hours. He’d given me such illuminating stories for my research of the Korean War. But this veteran had one last lesson for me. And I stumbled on it unsuspectingly. I asked the former sniper with the Royal Canadian Regiment what sort of emotions he’d felt during his time overseas.

“No such thing,” he told me. “Emotion was a luxury we had learned to give up in the army.”

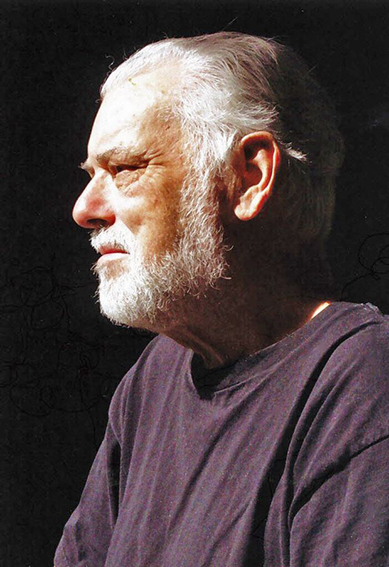

I know it’s now 11 days past Remembrance Day, but I learned this past week that one of my longest veteran acquaintances, Ted Zuber, died at 86. Not only does this Canadian’s story deserve to be read, but Ted Zuber’s wisdom needs to be heard, weighed and passed on. He and I met and spoke many times over the course of my research on the Korean War between 1997 and 2000.

But we also shared common and disparate views of the world, wondered long and hard about the nature of war, and estimated just how deeply Canadians were injured by wounds in these conflicts. The first time I interviewed him, in the confined sleeping quarters of his pick-up truck cap, we both were attending a reunion of Canadian Korean War vets at Petawawa, Ont.

Zuber – the photographer, teacher, singer-songwriter and skydiver – had travelled from his home and art studio in the country north of Kingston to join the reunion. But throughout most of the official proceedings, the man sat apart from others who shared harrowing tales of patrols into no-man’s-land above the 38th Parallel, nights freezing in forward observation posts on Little Gibraltar, and drunken parties at Gisha clubs when on-leave in Tokyo.

Oh, he had plenty of harrowing tales too. But he’d always been a sniper, meaning he nearly always operated alone, with little or no regimental contact, and with relative impunity.

Like so many other volunteers, in 1950, that first summer of the Korean War, Zuber joined the Special Force for Korea because he felt he’d missed out on serving overseas during the Second World War. The army took note of his sharp eye as a photographer and trained him as a sniper.

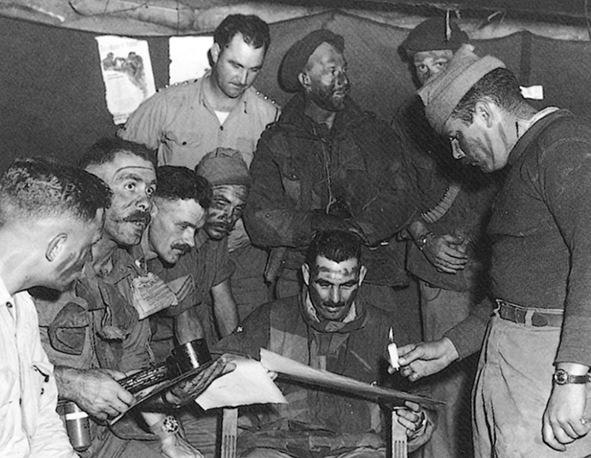

By October 1952, the RCR had deployed him to the front lines at a place called The Hook.One night, Zuber took the opportunity of a break in the action to catch up on some sleep in a tunnel beneath the position. Beside him underground were a combat engineer, two South Korean labourers, a signaller friend, and about 20 new recruits. The reinforcements were preparing their weapons for the night’s deployment. One of the men was told to prime a box of a dozen grenades in the tunnel.

It was about midnight when one of the grenades he had primed slipped from his hands. The resulting explosion decapitated one of the Korean workers, broke the engineer’s leg in two places, blew the signaller’s foot off, and peppered shrapnel into the back of Zuber’s legs and buttocks.

“It’s something you never see in the movies,” Zuber said. “No matter how realistic the movies get, they don’t show the concussion. It’s the blast!”

Zuber explained that, with shrapnel wounds all over his back, he and the surviving South Korean labourer suffering severe chest wounds, were taken to a regimental aid station, manned by medics and medical officers. When Zuber directed a medic to the South Korean first, an officer noticed and shouted, “Hey! Our own first!”

Zuber was appalled and described the South Korean’s last moments, the creaking sound of the man’s unconscious struggle to breathe and his eventual stillness in death. Zuber wanted to feel sympathy and loss, but he admitted the war had removed that part of his personal response system.

“Emotion was something you just didn’t tolerate,” he said.

In some ways, Ted Zuber wasn’t fully able to realize that fact until after he’d returned to Canada. It happened when he pulled out some of the drawings he’d made in Korea. Most, he said, consisted of field renderings – sketches of buddies resting, showering, hanging their laundry, writing letters home and a few portraits behind the front lines.

When Zuber eventually decided to put his Korean War impressions on canvas, he realized those original sketches lacked something.

“I looked at them and they were emotionless … about as interesting as a topographical map. I hadn’t allowed myself to (feel) anything while I was there. So, the one thing I injected [into paintings] later was the emotion.”

Ted Zuber died at the end of October, perhaps not surprisingly on his own terms. The former Korean War sniper and ultimately Canada’s last official war artist – diagnosed with terminal cancer – chose to die in a medically assisted suicide in his art studio at his home in Kingston.

For him, perhaps appropriately, it was death without fuss or anguish, not on a battlefield, but still governed by the emotionless environment he’d known in a war zone. Just one of the lessons this veteran taught me.

Hello Ted… It’s Ted Zuber’s daughter, Linda Zuber. I tried to get a message to you about Dad’s passing and invite you to the celebration of his life, but alas the news didn’t reach you in time. Thank you for this article and honouring my father, Canada’s last official War Artist and a remarkable individual.