They called him “Doc.” But Fred Sutherland told me that he didn’t know anything about medicine. Somebody who came to see Fred off at the train station, when he left to join the Air Force in 1941, decided because Fred’s dad was a family doctor in that part of Alberta, that the son ought to be nicknamed “Doc.”

“He called me ‘Doc,’” Fred told me, with some embarrassment in 2017. “So, it stuck. All through the war they called me that.”

Like many parts of Fred Sutherland’s 95 years, so many who knew him thought the world of him. Friends and family always used superlatives and high praise whenever they spoke about him. They considered some things Fred experienced in his youth, incredible. They heard about his wartime exploits as a front-gunner aboard one of the Lancaster bombers on the famous Dam Busters raid of 1943, and called him brave. Then, shot down on a later mission, when he evaded the Germans for weeks and got all the way back to England, they call him heroic. And post-war that he survived yet another crash while working with Alberta forestry in the Rockies, they describe as a miracle.

“Sure, they were important events in my life,” he said, “but heroic? No.”

Fred Sutherland, who for some years has remained the sole Canadian survivor of the famous Dam Busters raid in WWII, died on Monday. But it wasn’t as if Fred set out to be famous. About the only time he was obsessed about anything was in the 1930s when bush pilot Punch Dickins landed his famous Bellanca float plane along the riverbank in Peace River; adolescent Fred was desperate for a plane ride. Dickins told Fred if he came up with $3 he’d take him up.

“I got three bucks off my dad, and got the flight,” Fred said. “I thought I’d become a bush pilot too.”

Sutherland got his wish to fly again, but in wartime not as a pilot; the RCAF recognized his marksmanship and streamed him into Bombing & Gunnery School. By 1942, he’d gone overseas and completed a tour with Bomber Command, surviving difficult raids against such industrial targets as Cologne, Essen and Berlin.

He remembered many night flights to the target when he fired bullets and tracers designed scare off German night-fighters, when “the only person they scared was me!” I asked him about being scared on the famous low-altitude raid against the dams in the Ruhr River Valley in 1943.

“We went low-level – 60 feet above water or ground – all the way,” he said. “It was all industrial area, so everywhere there were high-tension wires. We were on constant lookout. That was really scary.”

The Dam Busters – and there were 30 Canadians among the 19 Lancasters that pulled it off – managed to breach two dams and damage a third. Fred’s crew (aboard Lancaster AJ-N) breached the Eder Dam. When they got back, the RAF took publicity photos of them. The King and Queen visited Scampton, their bomber station, to thank them personally.

But “Doc” Sutherland just wanted breakfast, some rest and a chance to grieve. “Some of us lost roommates, best friends, that night.” But loss in his wartime career never stopped. On his next operation, Fred’s bomber lost power on two of four engines and if not for the skill and courage of pilot Les Knight, none of the crew would have survived. Fred bailed out and evaded Germans for nearly three months.

Fred Sutherland had served his country above and beyond. When he arrived home in Peace River, a local preacher pointed out that the congregation had prayed for his safe return, suggesting that’s why he’d returned safely. Fred politely commented, “You can pray all you want. It wouldn’t have changed the outcome,” he said. “It was just luck.”

Clearly, Fred hadn’t used up all of his portion. On a fire observer flight into the Rockies in the 1970s, the Cessna plane in which he was a passenger crashed into a mountainside. He was later rescued by helicopter; that was his last working flight.

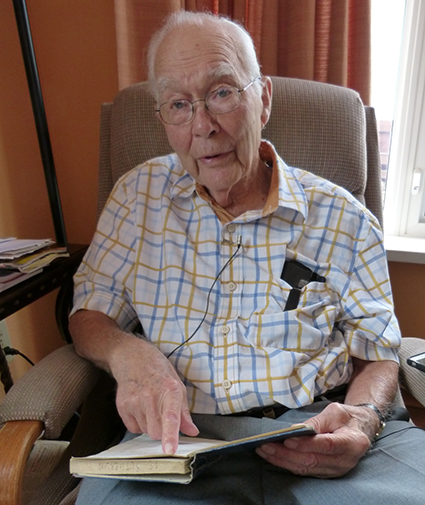

Those few days we spent together, as I interviewed Fred Sutherland for my book a couple of years ago, I found him soft-spoken and direct. When it was time for him to assist his ailing wife Margaret, our conversation had to wait. Then, he’d make sure I knew how proud he was of his children and grandchildren before we returned to the subject of his war stories. In all our shared time, during my visit to talk about the Dam Busters raid, I only heard Fred use a superlative about himself once.

“I rarely talk about this to anybody,” he commented at the end of our visit together. “But I never forget it. It’s the most important thing that ever happened to me.”

A man whose accomplishments reached great heights, Fred Sutherland was as well-grounded a person as I’ve ever met.

Interestingly, tonight I just finished reading Chapter 9 “The Op Too Far” that describes the loss of 5 of the 8 Lancasters and killed 41 of the crew in Operation Garlic. I was particularly impressed with your description of Doc Sutherland’s effective trek through Holland and final return to England and then home to Peace River. When you spoke at our Escarpment Probus Group in November, he was the last surviving Dam Buster. I decided to search his name and found your article that he died just a few days ago on January 23rd. I enjoyed reading your account of your interview with this modest and remarkable man! Thank you for your well-researched book on this most important event in the history of WWII.

Sir, If and when you have timeI would be obliged if you could let me have the names of all the Canadian aircrew on the Dam busters raid, I am trying to trace my anticedentd .

I thank you in anticipation of a reply.