The last time I spent time with Ted Arnold was in 1991. He had contacted me about his Second World War story. So, I travelled to Port Hope and interviewed him. We communicated again later in the year when he was holidaying in Florida. And while I thought of him often after that, I never actually saw him again. His son Rick contacted me some years later.

“We were wondering if you could help us?” he asked.

I said I would try and then Rick explained that his father had slipped through the cracks at Veterans Affairs Canada. Partly because he was born in Argentina, but mostly because he fell into an odd category as a veteran, the system had denied him veteran status, and therefore funds to cover the expenses at an assisted-living facility in Ontario.

“As you know,” Rick Arnold went on, “he’s not entitled to a veteran’s pension.”

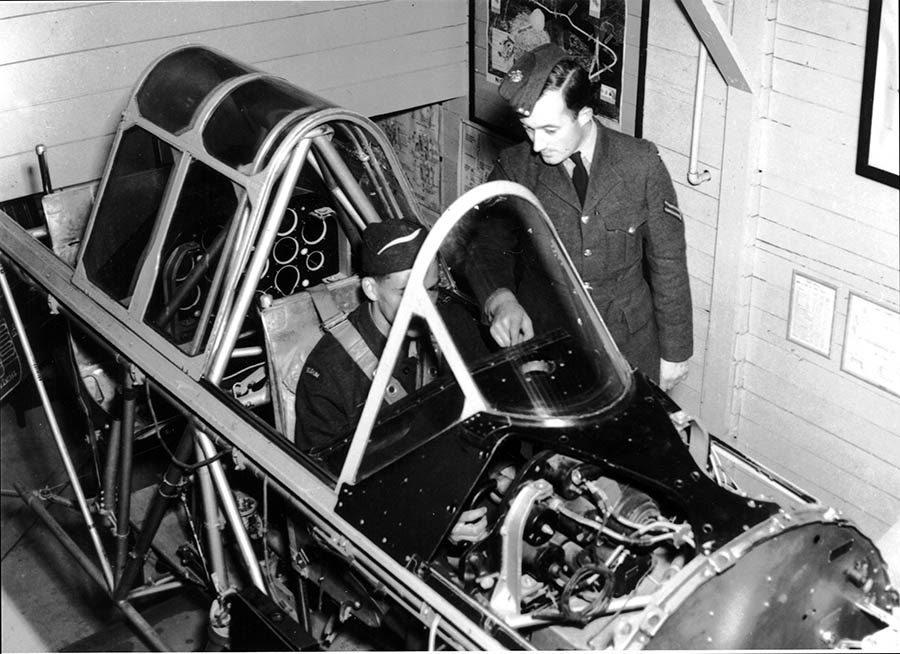

It was one of the vagaries of Air Force service in Canada. In 1939, when Ted Arnold learned that Canada had declared war on Germany, he trained, planed and hitchhiked from Argentina to Canada to enlist in the RCAF. Within a year he’d completed pilot training, but because he’d graduated on top of his class, those running the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan decided to keep him in Canada as a pilot instructor to teach the next classes of students coming through the Plan. He taught another course and another. He never did get overseas to serve in fighter or bomber aircraft. His file was marked “Too Valuable to Risk,” meaning that he would stay an instructor for the duration of the war.

Flight Lieutenant Ted Arnold never left Canadian shores, consequently neither the RCAF nor the Canadian government considered him officially a veteran. And when Ted lost his health in his 80s, there was no safety net because he’d never been considered a combat veteran. At the time, I wrote an appeal explaining though F/L Arnold had not flown Spitfires or Lancasters in combat in enemy skies, that he’d taught hundreds of others how to, and to survive. He’d given other young airmen the skills to win the air war, but because of the narrow definition of veteran – someone who served offshore – instructor Arnold was never considered like his students, a veteran.

Things have changed for veterans … sort of. The Liberal government’s new medical benefits system kicked into effect on April 1, this week. It’s called “a medical pension for life” and is supposed to give lifelong financial support to veterans with physical or mental injuries associated with their military service.

It replaces “lump sum medical benefits,” a system that the Stephen Harper Conservative government introduced to buy off veterans and eliminate them from federal budgets.

But the PTSD assessment portion of the plan depends on someone at Veterans Affairs Canada – a physician, a psychiatrist or a registered psychologist – conducting an interview with the candidate to determine eligibility. In the new system, once the interview questionnaire is complete, VAC adjudicates each case. According to Chris Rose, one of those psychologists assessing veterans, the problem is that the old questionnaire included four types of post-traumatic stress disorder. The new one includes just one:

“[Are you] re-experiencing traumatic events? Yes or No?” Rose told CBC Radio on Tuesday. “And that symptom [is] the only one that may or may not be characteristic of PTSD on the entire questionnaire.” Rose said, based on the new questionnaire, PTSD no longer exists.

In response to such criticism, VAC says that the shorter questionnaire and simpler definition will streamline things and ensure vets are better served. Between March and December of 2018, there were 21,000 Canadian vets receiving disability benefits.

“It’s a useless document,” claims Barry Westhome, a now retired warrant officer with the Canadian Armed Forces, also interviewed on CBC; he served in the Canadian operation to Haiti, and was diagnosed a dozen years later with PTSD. He used to help process other vets seeking assistance, but has recently resigned in protest. He suggested that attempting to complete the new forms for the “medical pension for life” coverage and PTSD questionnaire are more complicated than figuring out one’s taxes.

“This paper actually causes PTSD,” he said in frustration.

Back in the 1990s, When Ted Arnold’s son and I attempted to penetrate VAC’s red tape on the issue of who is a Second World War veteran, we realized that we couldn’t change the definition. We had to change the thinking. We had to put a VAC civil servant, who’s never faced what Canadian soldiers, sailors and aircrew faced between 1939 and 1945 into their shoes. Sadly, Ted Arnold died before we could win him benefits to cover assisted-living costs. Little has changed, say the veterans.

The system appears to follow an age-old axiom: “Deny. Delay. And die,” when dealing with clients.