We met a hundred feet underground. The walls around us consisted of a seam of iron ore. It was about six degrees Celsius in there, but she said the temperature never changed year-round. At one point, when she turned out the lights and lit a single candle, she explained that was all the light miners had during their digging shifts – 10 hours a day, six days a week – year after year.

Then, she made the whole place human. She said her dad had worked there in the 1950s, lost the lower part of his leg in a mining accident, but was able to joke about it.

“He wagered strangers, he could put a foot down in one spot and his other 25 feet away,” she said. “When they bet he couldn’t, he took off his prosthetic foot and tossed it 25 feet away.”

Our tour down the No. 2 Bell Island Mine and Museum, in Newfoundland, could have bored me to tears. After all, as we discovered, it was just a 600-foot-long, 17-foot-wide hole in the ground, dark, cold and responsible for some of the bleakest conditions working people in the deeps in Atlantic Canada have ever known.

But because our guide, Geraldine Hibbs, related it to her father, somehow the place seemed almost human. Every once in a while, she asked those of us on the tour, last Sunday, if we were feeling cold.

“We’ve got lots of shovels lying around,” she said sarcastically, “if you want a bit of exercise.”

In its heyday, this mine that stretched for kilometres under the Atlantic Ocean floor, gave work to thousands of Newfoundlanders. And its miners yielded some of the richest deposits of iron ore in the world, shipping them as far away as the U.S., Scandinavia and Germany.

In fact, when the Second World War broke out, Nazi U-boats torpedoed and sank four ore carriers docked at Bell Island to prevent the ore from getting to wartime steel producers in North America. But the mine closed in 1966 and the population of Bell Island shrank from 12,000 to 1,400 almost overnight.

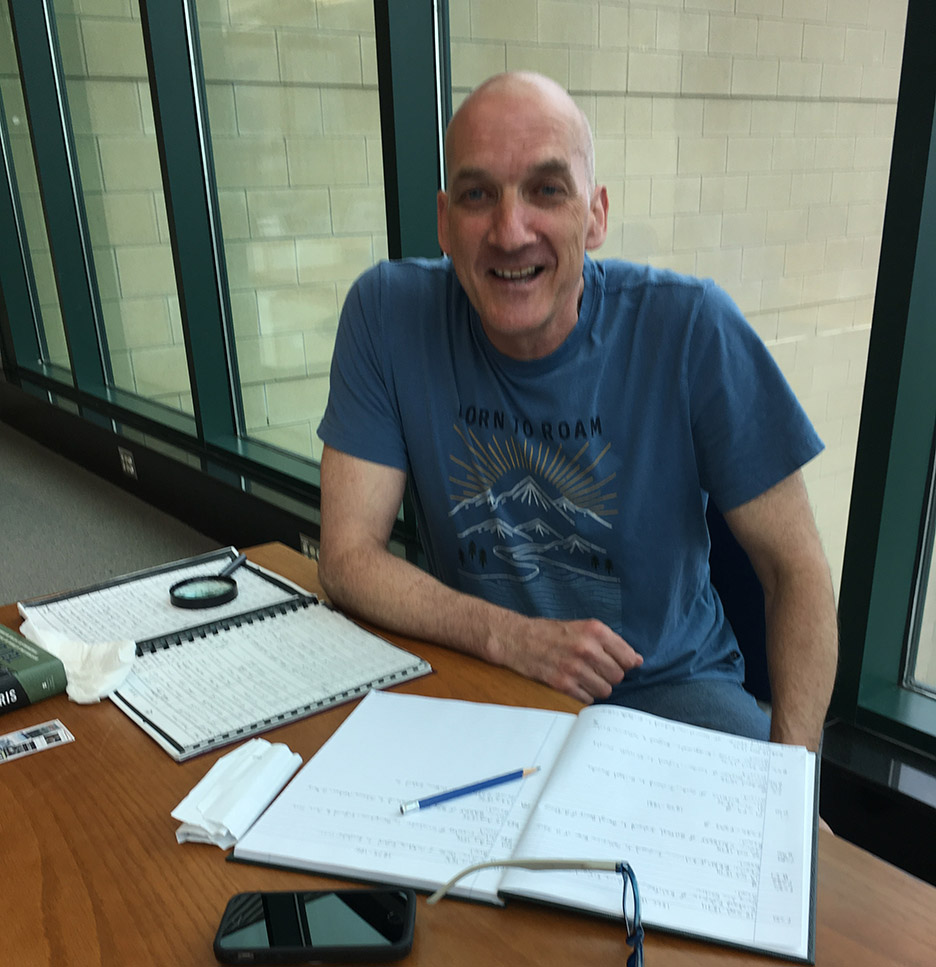

At the St. John’s museum known as The Rooms, we explored the province everybody here calls, “The Rock,” from its prehistory to its 21st century cultural heroes. But I knew I’d found the marrow of this place when I sat with local archivist Gene Quigley, who’s compiled personal Newfoundland history from its rich Irish, Scottish and English roots, to its Second World War heroes.

“Back in 2008, nobody’d bothered to ask the vets any questions,” Quigley said, “So I did. And I discovered the way Newfoundlanders served and died in the war.”

When it was finally time to stop touring and rest our weary tourist bones, over the weekend, we found what could have been just another anonymous watering hole in St. John’s. Stuck between a federal office building and one of those picture post-card, “I am yellow today,” downtown residences, a narrow staircase led to a third-floor doorway.

“This is a private officers’ club. Members only,” the sign on the door read. “Make yourself known to the staff.”

Which we did. The bar inside was nearly empty of patrons when – as the sign instructed – we identified ourselves. And we could have sat there quietly taking in the collection of decades-old crests, plaques and navy artifacts occupying every nook and cranny of the place.

Except that, like in the Bell Island mine and the St. John’s archives, the Crow’s Nest officer’s club has a bar manager who’s a raconteur. Joy Griffin dazzled us with the tales of dignitaries she said had visited the site of the Crow’s Nest – Admiral Nelson, Captain Bligh (of “Mutiny on the Bounty” fame), and during the annual Confederation masquerade night, Winston Churchill, Amelia Erhardt and Newfoundland’s father of Confederation and first premier, Joey Smallwood.

“But the best of them all though was Arthur Barrett,” she said. “Pilot who flew tours in Bomber Command during the war.”

She looked to the stool where Arthur sat for years, and she spoke about him as if he were still there, at age 95, regaling patrons about aircrew he’d known, missions he’d flown and the hard-fought victory they’d brought home.

Joy told us Arthur had lost a brother in the air war, but after the war returned to Newfoundland, worked as a broadcaster, and brought drama and classical music to outports around the province. She missed him dearly.

“I feel lucky to have known him,” Joy said.

When we’d finished our refreshments and paid our tab, we knew we’d enjoyed the best travel experience of all. Our thirst for some Newfoundland history had been quenched not by facts, figures and glass-encased artifacts, but by guides, archivists and bartenders who offered the stories of real people who’d lived extraordinary lives kept alive in an island tradition of aural storytelling.