It seemed an unspoken rule by the time I got there. Every step was deliberate, unobtrusive and (I hoped) non-destructive in this place of nature. I made my way through sage and other prairie grasses, closer to a mound where a couple of prairie dogs were playing. I didn’t want to scare them down their hole; I just wanted to get close enough to take a clear photograph. Then, I looked down and suddenly there it was.

A prairie dog emerged from a hole in the ground right at my feet. And he, or she, chirped at me, as much surprised to see me lording overtop, as I was to see an animal nearly under foot.

I aimed and fired my camera and got the picture.

Speaking of chirping, everybody’s been chirping about the environment lately – whether the politicians fighting over pipelines, carbon tax or the seemingly relentless march of climate change. And I’m as concerned as anyone about keeping air, water and land pristine for our children and grandkids. But sometimes the debates and Armageddon feel so out of my hands.

This week, I travelled into a Canadian environmental gem where the rules of saving nature are obvious and the means of preserving it very much in human hands. Grasslands National Park, created in 1981, occupies about a thousand square kilometres of hills and valleys, in the Frenchman River Valley, in the far southwest corner of Saskatchewan; in fact, if I’d driven about 10 minutes south of the park, I’d have crossed the international border and entered the state of Montana.

This week, I travelled into a Canadian environmental gem where the rules of saving nature are obvious and the means of preserving it very much in human hands. Grasslands National Park, created in 1981, occupies about a thousand square kilometres of hills and valleys, in the Frenchman River Valley, in the far southwest corner of Saskatchewan; in fact, if I’d driven about 10 minutes south of the park, I’d have crossed the international border and entered the state of Montana.

At the Grasslands visitors’ centre, the Parks Canada official said: “If you take the self-guided eco-tour, the rule is, ‘Watch your step!’”

I cocked my head as if to say, “For what?”

She reminded me this was “Grasslands Park,” and that “70 per cent of the park’s area is covered in indigenous and rare grasses.” She showed me pictures of wheatgrass, needle-and-thread grass, June grass, blue grama grass, coneflower, gaillardia, blazing star, and prairie clover, and said, “So, stick to the pathways.” She also told us to drive slowly through areas populated by black-tailed prairie dogs, since the worldwide population of the species sits at about 3 per cent of its original size.

“Let’s not squish any of them unnecessarily on the park roads,” she said. My experience with the gopher at my feet made that clear.

But it’s not as if the only thing to dodge in Grasslands National Park are prairie dogs and blades of prairie grass. No. We were also warned about the scores of bison that roam the park. “If you see them,” the park official said, “don’t consider them tame and get out of your car to get nifty close-up pictures of them. It’s calving season and the cows are particularly protective of their young,” she said.

We were also informed about the important First Nations content of the park. Over centuries of pre-history, indigenous members of the Gros Ventre, Assiniboine, Cree, Blackfoot and Sioux had hunted, fought and settled on these lands.

I remembered research I’d done on one First Nations group in particular that had traversed this land – members of Sitting Bull’s Lakota Sioux who’d fought the U.S. Cavalry at the Little Big Horn in June 1876 – and then sought sanctuary here after the battle – crossing what they natives called “the Medicine Line” (the international border). However, they were persuaded by newly arrived North West Mounted Police Insp. James Walsh to return to the U.S. peaceably. They did, and not a drop of blood was spilled on the hills and valleys of what is now Grasslands Park.

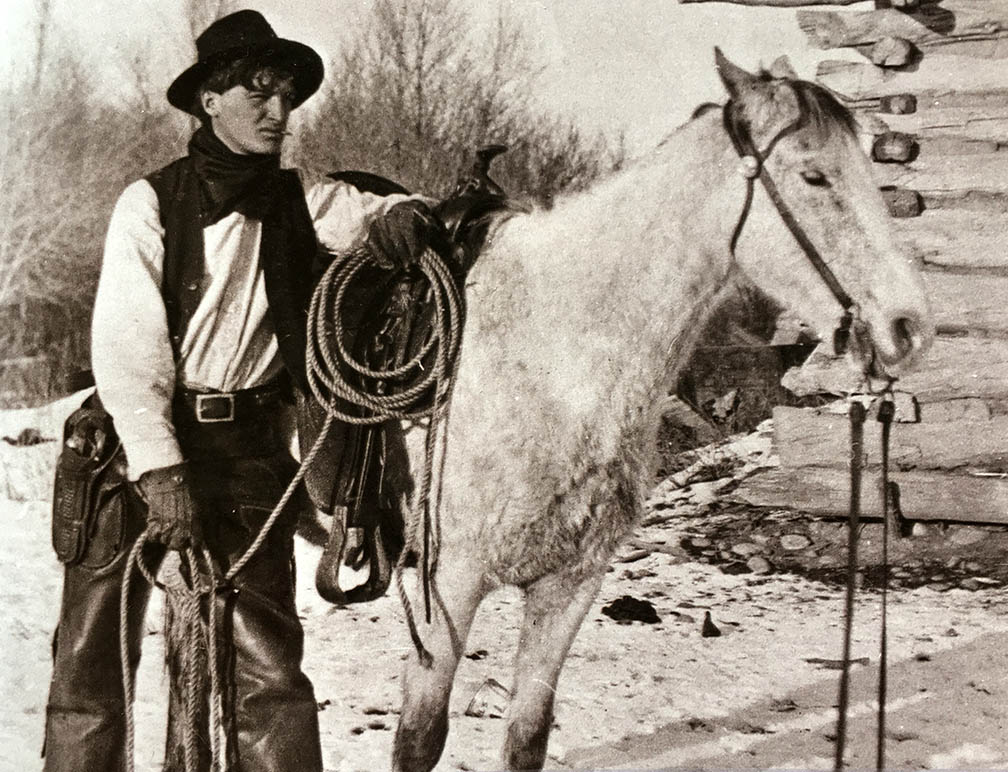

But there was also some mystery to this place, mystery associated with latecomers (after the First Nations) who ranched here. Again, walking carefully through grass near the Frenchman River, I learned about the legend of Will James, who’d homesteaded and raised livestock here about 1911.

Apparently, James was not his real name; he’d left Montreal as 15-year-old Ernest Dufault, had worked on the fabled 76 Ranch in the area, and went on to become famous in Hollywood as a cowboy writer and illustrator – not as Dufault, but as James. So, I walked carefully around the former dug-out barn and home where James had lived, as not to disturb any ghosts.

Oh yes, and there was one other life form the Grasslands Park officials warned us about. “There are rattlesnakes in the park,” she said. And I waited for the other shoe to drop. “They’re not interested in you unless you disturb them. So, give them the right of way.”

I kept that top of mind too, as I dodged rare grass specimens, prairie dogs, bison and snakes this week at Grasslands. Maybe coping with the global environmental crisis is not dissimilar. Walk carefully among fragile sage and angry rattlers and everything will be just fine.