When he turned 18, in 1941, Roger Parliament travelled to a recruiting office in downtown Toronto to join up for wartime service. He’d prepared all his enlistment papers and anticipated vision and hearing tests.

But perhaps the most critical part of his decision to enlist in the armed services occurred when he came before the second-in-command at the recruiting office on Bay Street.

“I’ve decided to join the Air Force,” he told the pilot officer he faced.

Across the table from him was Pilot Officer Garnott Parliament, Roger’s father.

His father had served in the Great War in the Royal Flying Corps, but was too old for service in the RCAF in the Second World War. So, father and son concluded it was perfectly acceptable Roger should follow in Garnott’s footsteps into the Air Force and gave him the nod.

“I was 18 and ready to serve my country,” Parliament Jr. said.

I met Roger Parliament this week as he and 25 other Canadians joined me on an overseas tour exploring former Second World War bomber bases where almost every night from 1939 through 1945, Canadian aircrews flew from airfields with names such as Middleton St. George, Skipton-on-Swale and Linton-on-Ouse to bomb targets in Nazi-occupied Europe.

The odds of airmen surviving such bombing missions proved horrendous. On average for every 100 Bomber Command aircrewmen, 59 were killed in action, five wounded, 11 became POWs, and about 25 might successfully complete a tour of 30 trips.

“When I got to England, they handed me a pair of shorts and a pith helmet,” Roger explained. “On board ship, I learned we were headed (to serve as ground crew) to North Africa.”

Serving in the desert heat of Algeria and Tunisia proved to be another of numerous unexpected turns Parliament would experience in his wartime career. During our tour of Bomber Command stations this week, our group also visited the majestic Lincoln Cathedral, in Lincolnshire.

We met Jeannette Davies, who guided us through the cathedral’s service chapels commemorating Commonwealth armed forces in the Second World War. Just as war had taken Roger Parliament in unexpected directions, so did it change Davies’ life in England beginning Sept. 12, 1944.

“When I was 10 months old, my father was shot in the head during a bombing raid against German targets,” she said. “He had to be extracted from the rear gun turret of his Lancaster bomber.”

At intensive care facilities for brain-injured veterans, in England, doctors gave Jeannette and her family little hope that her father, William Nichol, would recover, much less lead a normal life. Not only were the specialists wrong, but Nichol also overcame the loss of half his brain tissue to be able to walk again and teach at the university level.

His ability to adapt proved miraculous, according to his daughter. Said Jeannette in the Air Force Chapel at Lincoln Cathedral, this week: “My father was a fighter who fought for everything the rest of his life.”

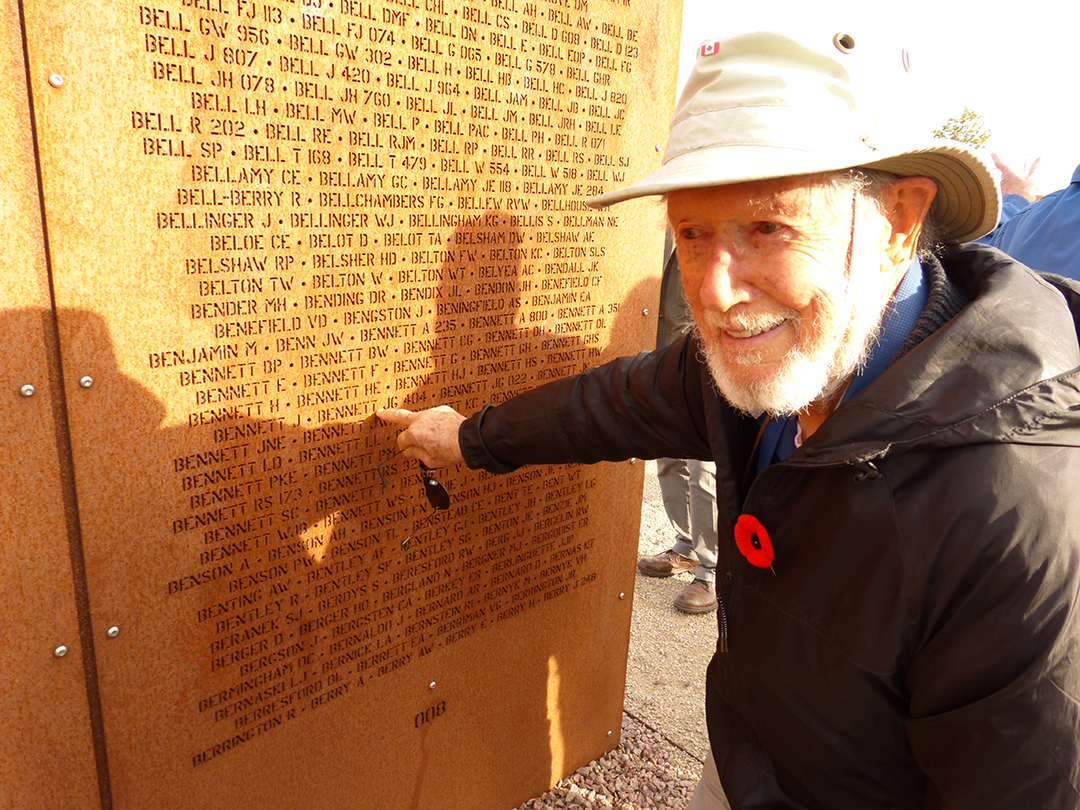

The war threw wartime turns at another of my fellow travellers in England. Cliff Bennett joined us from his home in Carlton Place, near Ottawa, as we travelled the roads to and from former RAF air bases in Yorkshire this week. In particular, Cliff felt drawn to a still-operational base at Linton-on-Ouse north of the City of York. On a January night in 1944, his cousin, Pilot Officer James Bennett, flew with RCAF 408 Squadron bombers against targets at Berlin. P/O Bennett did not return.

“He was one of 12 men from Carlton Place (serving in Air Force) killed in action,” Bennett said. He then elaborated that more than 40 men in all from his small town of 4,000 had died in the Second World War, more than the community’s fair share of loss. Indeed, Cliff noted that their loss went much further than grieving and mourning.

“After high school Jimmy got a job as a milkman at the Carlton Place Dairy,” Cliff Bennett said. “And as a kid, I used to jump on his horse-drawn wagon and help him.” So, when Cousin Jimmy died on operations in 1944, Cliff noted that post-war his hometown knew it would have to find a new milkman.

In contrast, one other turn in airman Roger Parliament’s wartime life became an overwhelming but positive experience. Late in the war, his squadron learned its military awards ceremony would be visited by the Royal Family. So, LAC Parliament had to shine buttons, polish boots and trim his hair for the ceremony.

As fate would have it, during the Royal inspection of the squadron, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth stopped to speak to the airman right next to LAC Parliament; consequently, directly in front of Roger stood the King’s and Queen’s daughter.

“Princess Elizabeth was smack in front of me,” he recalled. “Eighteen years of age and what a beautiful lady. All I could do was look straight ahead. I’ll never forget it.”