It wasn’t quite the fall classic, but it did happen in the fall … the fall of 1943. Sometime into the fourth of fifth inning of this baseball game, the umpire behind the plate threw up his hands and marched to the mound. A man in ordinary pants and shirt, and a pair of well-worn Air Force boots stood where the mound should’ve been (were this an official baseball park, but it wasn’t) and waited to hear what the umpire had to say.

“Bill, the Americans haven’t managed to hit the ball out of the infield,” Larry Wray said to pitcher Bill Paton. “Let’s make this game a little more competitive.”

The Americans to which Larry Wray, the senior Canadian Air Force officer in this WWII prison camp in Poland, referred, were American POWs from the South Compound of Stalag Luft III camp near Zagan, Poland. Yes, this was the infamous camp where later that winter a breakout of some 80 Commonwealth airmen would occur.

But for now, this was a baseball game (a.k.a. a way of distracting the Luftwaffe guards in the camp). And Canadian pitcher Bill Paton was enjoying every minute of it.

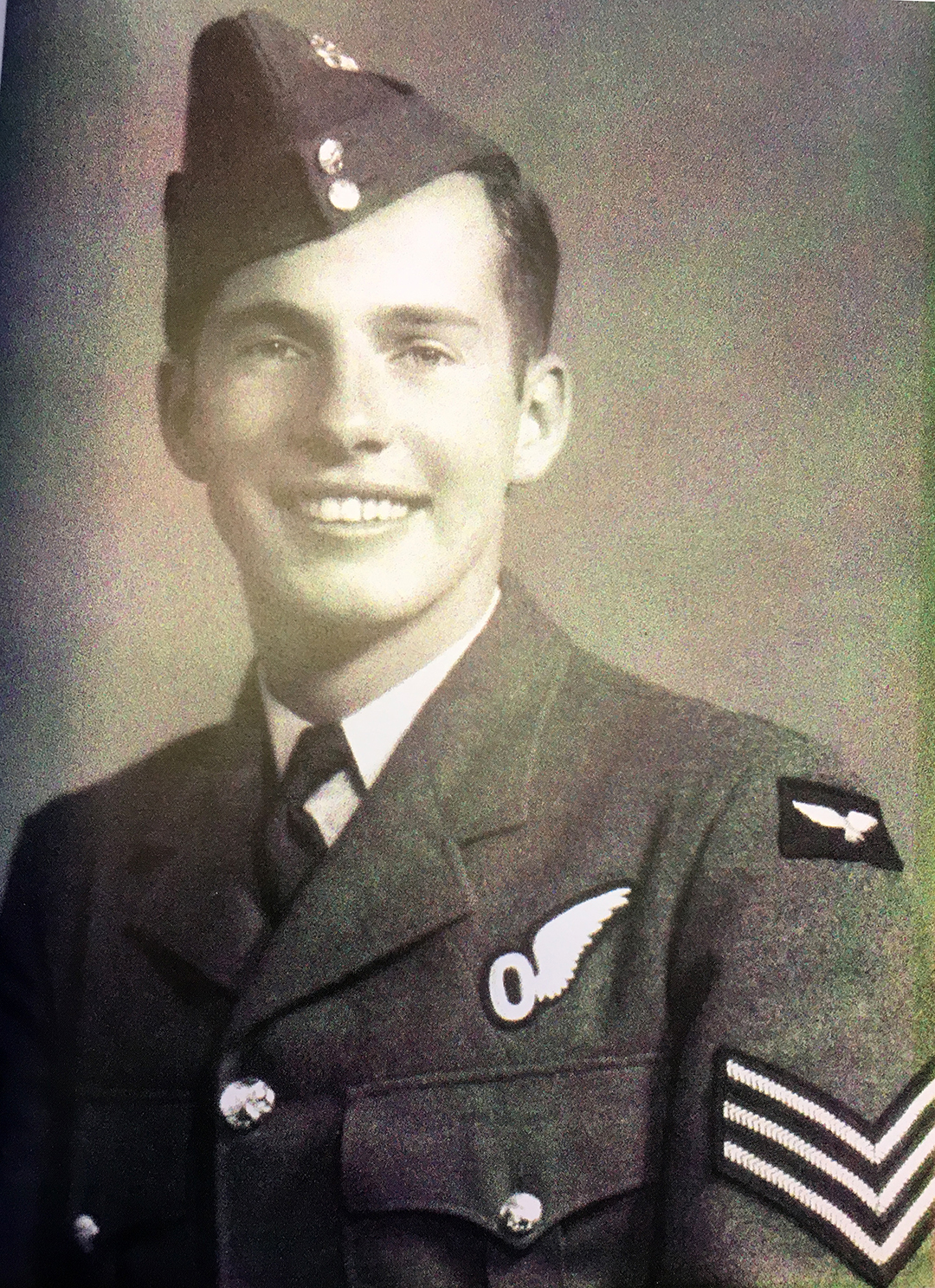

With the 2019 World Series just completed, baseball writers have filled the sports pages with ample hyperbole about the stress that players endure at the big-league level. Indeed, some sports pundits have gone so far as to say the pitcher, in such situations, must feel like a warrior in mortal combat. With all due respect, nobody has the right to make such a claim … except Second World War airman William Edgar Paton.

You see, Bill Paton was an RCAF flight lieutenant who flew bombing missions over Germany during the war. Nightly, he and his crew ran the gauntlet of enemy anti-aircraft fire and Luftwaffe night-fighter attacks. It was a campaign that would claim the lives of no fewer than 10,000 Canadian airmen between 1939 and 1945.

Still, F/L Paton and his crew carried on mission after mission over Nazi-occupied Europe. Then, on his seventh op, Bill’s aircraft was shot down, and Paton and his crew mates had to bail out to save themselves.

Once on the ground, Paton faced an attack from a civilian with a pitchfork in retaliation for the bombing raid. Then, shipped to a prisoner-of-war camp in western Poland, Paton was left to wait out the war in the North Compound of the infamous Stalag Luft III POW camp.

Because all Allied airmen felt duty-bound to attempt to escape such imprisonment, however, F/L Paton joined the camp-wide Escape Committee; he worked as a “stooge” protecting the secrecy and security of the tunnels (“Tom,” “Dick” and “Harry”) being constructed secretly between April 1943 and March 24/25, 1944, when the largest wartime POW breakout occurred, otherwise known as “The Great Escape.”

Helping the Escape Committee to keep the German guards distracted and off-balance, the Stalag Luft III inmates organized baseball tournaments, sometimes including games against the POWs in the South Compound which housed American POWs. Naturally, the U.S. airmen considered their teams unbeatable playing their “national pastime.”

What the American all-star team hadn’t expected was that the Canadian all-star team included a seasoned pitcher, none other than F/L Bill Paton. One of the Bill’s teammates, POW Art Hawtin, from Beaverton, Ont., picks up the story:

“The Americans made arrangements to play us twice,” Hawtin told me in an interview a decade ago. “But we had Bill Paton pitching for us. He’d pitched senior ball for the Beaches League in Toronto. Bill struck out 16 batters.

“That’s when umpire Larry Wray stopped the game, went out to the mound and asked Bill to give the opposition a chance to get back into the game. The Americans hadn’t scored a single run to that point. Wray asked Paton to let them hit. But Bill dug in. In the first game we didn’t get many runs, but we got enough to win. The second game wasn’t even close. We won 14 to one.”

I corresponded with Bill Paton while writing my account of The Great Escape, years ago. After the book came out, we stayed in touch, recalling the miraculous and tragic events of The Great Escape.

Many of the officers the German SS later assassinated in the wake of the escape, were Bill’s close friends. He never forgot them, nor the cost of war. Then, just past his 100th birthday, former F/L Paton also passed. His son John contacted me this week to say they’d be having a celebration of Bill’s life this Remembrance Day.

So, don’t let sports aficionados claim that modern baseball players look anything like combatants at war. Only one man can make that claim – F/L William Edgar Paton – who pitched his Canadian POW team to a win behind the wire at Stalag Luft III, and furthered his Air Force’s push to victory in the skies over Europe.

We’ll not see his kind again – on the mound or in the air.