He entered the hall a few minutes before the historical society began its monthly meeting. With a service dog at his side, he made his way to the last row of chairs and quietly sat down. His chocolate Lab settled beside him, and the meeting began. The chair of the society welcomed everybody, in particular the first-time attendees.

“Welcome to all our regular members,” she said, “and to those here for the first time too.”

I could see that being centred out that way made the man in the back row a bit uncomfortable. But friendly smiles were exchanged between the society chair and the new faces and the atmosphere became relaxed.

Once the chair had completed the society’s business, she handed things over to me and I began a presentation, based on my recent book, about military medical personnel in wartime. I spoke about stretcher bearers and nursing sisters in the Great War. I offered the story about Jonathan Letterman, the inventor of the very first field ambulance during the U.S. Civil War. I showed images and played sound of more modern medics from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. And I told the story of my own father, Alex Barris, and his trials as a medical corpsman in the Battle of the Bulge during the last winter (1944-45) of the Second World War.

All the while, I kept an eye on the man in the back row. And because he had that chocolate Lab by his side throughout the evening, I sensed that he’d served in the armed forces, and that maybe his service dog accompanied him to help him cope.

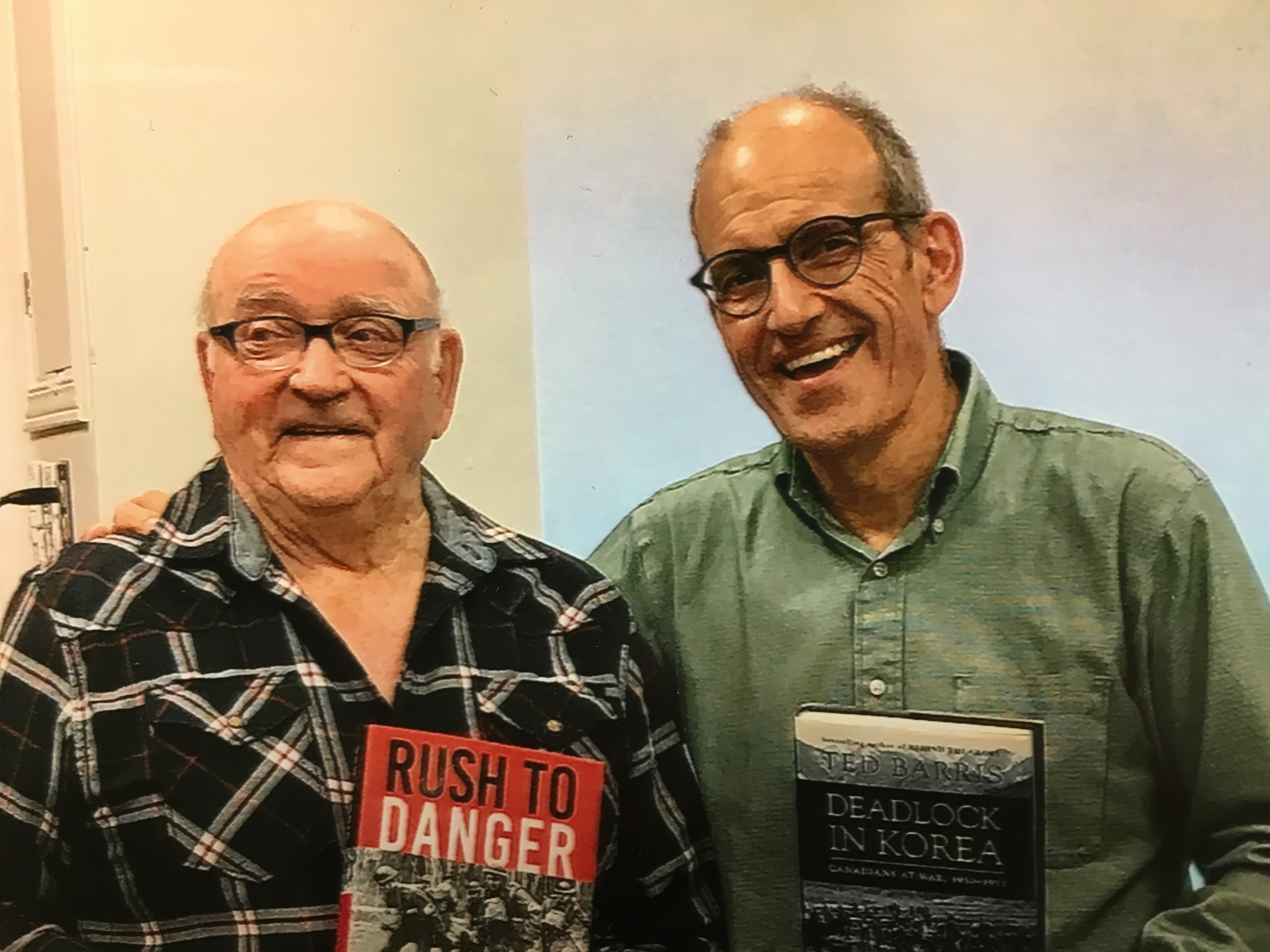

He’s not the only serviceman or woman I’ve discovered in my audiences this past fall. About a month ago, I travelled to the Fort Erie Public Library. As I have often these past weeks, I covered a few stories about the Korean War in my presentation.

In particular, I’ve offered some analysis of perhaps the most famous Korean War medical team ever – the members of the mythical 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH). For those who don’t recall, the 4077th appeared in M*A*S*H, a TV situation-comedy on U.S. Television from 1972 to 1983. Through 256 episodes, regular viewers watched military medical staff – Hawkeye, B.J., Hot Lips Houlihan and Klinger, among others – regularly dash to inbound helicopters delivering the wounded from fighting along the 38th Parallel dividing Communist North Korea from “the democratic” South.

But what most of us didn’t realize, I don’t think, was that Larry Gelbart, the writer behind the series, gave each show a strong sense of reality by first interviewing Korean War military medical vets, before scripting the clever teleplays in the series.

Anyway, when I’d finished showing a few clips from the show and praising Gelbart’s brilliance, a man in the audience put up his hand.

“I became an army doctor’s assistant once in the Korean War,” Romeo Daley said. “We had a bunch of casualties from exploding shells. The doc started stitching up this one guy and told me to finish the job.”

In 1950, just after his 18th birthday, Daley left his home in Capreol, Ont., to volunteer for the Canadian Army Special Force in Korea. He served as a Bren gunner with Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry in Korea and on such battlefields as Little Gibraltar and the Hook. He sustained an injury himself when a grenade went off nearby. But the toughest job he faced was finishing that stitching job.

“The doc said I did a great job,” Daley told me that night in Fort Erie. “Couldn’t even see where the stitches had been.”

As invisible as the stitches Daley sutured into that patient, he admitted to me after my talk, were the traumatic feelings that crept into his life in the years that followed. Like so many of those military medical personnel I’ve interviewed, the adrenalin of the moment tended to mask the assault on their scenes of the things they’d witnessed. That’s why, this fall, telling such stories, I’ve been as mindful of what I’ve seen as much as what I’ve said.

Following my talk at the historical society, the man in the back row approached me to talk. He stammered a bit, and thought long about what he wanted to say. He patted his service dog before telling me what he’s experienced as a peacekeeper in Cyprus in the 1970s.

“Nights like this are hard,” he said, “but I keep at it.”

We all need to keep at it.