I don’t imagine it’s something you pay much attention to. When you rush into that well-known department store at Yonge and Bloor in Toronto to buy an umbrella or a birthday card or maybe even a coat with the store’s iconic green, red, yellow and blue stripes on it, maybe that’s when you stop to realize that the symbol is three and a half centuries old. Indeed, as we learned from a story published this week in the Toronto Star, the Hudson’s Bay Company store will be 350 years old come this May 2, 2020.

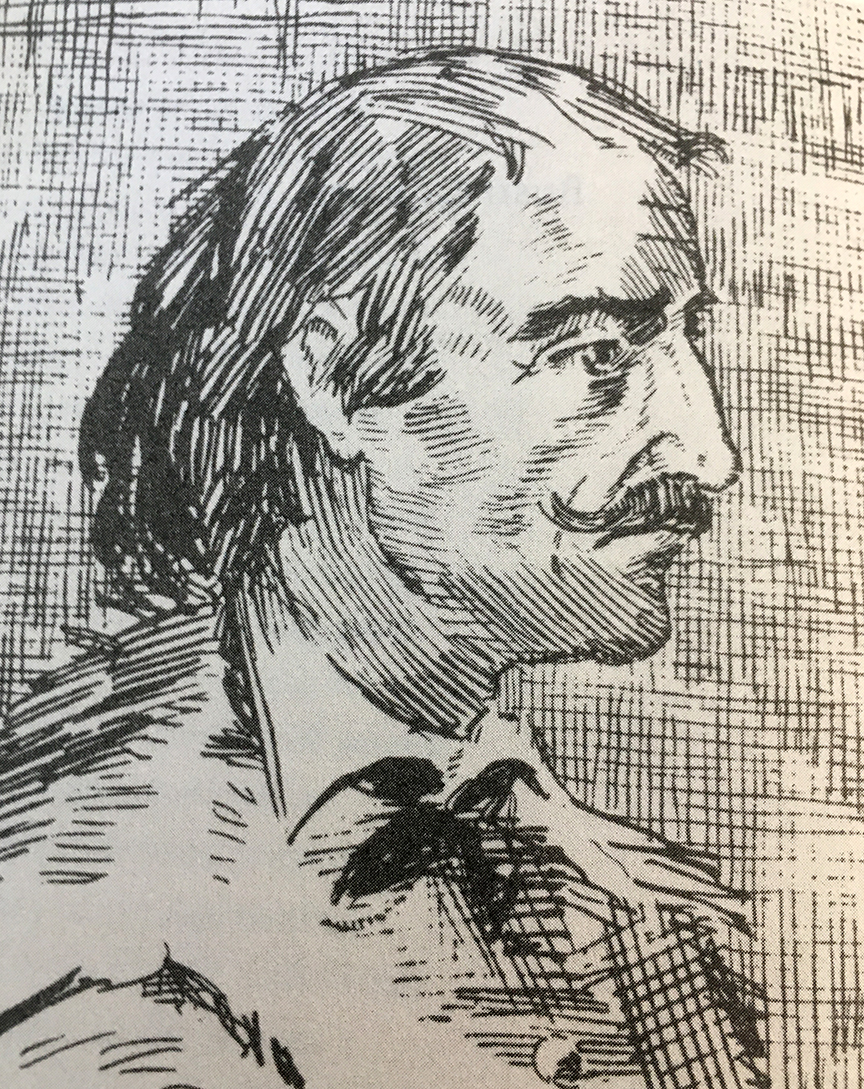

“What’s more, the history of the Bay and the history of Canada are interconnected,” says Mark Bourrie, long-time journalist, historian and author of Bush Runner, a book about Pierre-Esprit Radisson, the acknowledged founder of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC).

Indeed, when I received a ticket to a luncheon at the King Edward Hotel in Toronto last Monday afternoon, I had the good fortune to witness Bourrie and his book receive this year’s prestigious Charles Taylor Prize. The win entitled Bourrie to a monetary prize of $35,000 and recognition for having written the best non-fiction book of the year in Canada.

Coincidentally, Bourrie received the last Taylor Prize ever (as the foundation that has sponsored the award since the year 2000 will cease to exist). Ironically, news stories published this week also reported that Richard Baker, the executive chair of HBC, will take the retailer out of public hands. The so-called “company of adventurers” may disappear – via privatization – just as the Bay reaches its 350th birthday.

“So what!” I can hear some of you say.

Well, the survival of HBC symbolizes a great deal more than just department store umbrellas, cards and multi-coloured striped coats. As I learned from author Bourrie, the company and Radisson are synonymous with much of Canada’s 153-years of Confederation.

But while Bourrie does not cast Radisson in the traditional role of “explorer,” “fur trader” or “adventurer,” he does devote 314 pages of his book pointing out that Radisson was “a hardware salesman with some of the most fascinating customers in the world.” And many of those customers – First Nations people, Jesuit missionaries, Louis XIV of France, Charles I of England as well as countless other wanderers – would ultimately shape the culture, language and politics of the northern half of North America in the 17th century.

“(Radisson) is the Forrest Gump of his time,” Bourrie writes in Bush Runner. “He’s everywhere. And because he could read and write, he managed to tell us about it.”

And reading that story, I agree with Bourrie, is vitally important if Canadians are to understand their origins and perpetuate their nationhood.

But Mark Bourrie’s crusade to document such unrecognized heroes as Radisson, faces an even tougher challenge. The day before Bourrie learned that he’d won the Taylor prize, he spoke at a preview of the five non-fiction finalists.

He praised fellow finalist Robyn Doolittle (author of Had it Coming) for spending her life fighting to tell the truth, and Ziya Tong (author of The Reality Bubble) for her environmental writing “explaining the most complex difficult ideas and making people think.” He called Jessica McDiarmid (author of Highway of Tears about missing and murdered Indigenous women) “the bravest, most tenacious journalist I’ve ever met,” and complimented the fifth finalist, Tim Winegard (author of The Mosquito: A Human History of our Deadliest Predator) for “taking vast, complex ideas and knit(ting) them into a great story.”

But Bourrie also rang an alarm bell about the potential crisis in the writing and publishing of history in Canada.

“People are buying as many books as ever,” Bourrie said. “They’re just not buying the kinds of books that I, and my four colleagues, are writing.”

Statistics he quoted showed that Canadian books account for only 13 per cent of overall book sales, and non-fiction books only 4 per cent. And stats such as these, he said, send a clear message to non-fiction writers that no one cares whether they pursue their profession or not.

When Mark Bourrie won the 20th and final Taylor Prize on Monday afternoon, he worried that nobody would notice. “The end of this prize,” he said, “is evidence of a crisis in researched and accessible non-fiction. … We need to have a conversation about why this is … about book retailing, media and promotion, and frankly national self-esteem. Why do we as a country value ourselves so little?”

Sadly, his assessment is correct. That night, when I sat down to watch the evening news I neither heard nor saw any coverage of Mark Bourrie or the Taylor Prize. The annual ceremony occurred with little or no notice in the mainstream media.

Like the 350-year history of the Hudson’s Bay Company and Radisson, one of its co-founders, Canada’s non-fiction writing and its community of authors remain “comfortably forgotten.”

Ted,

Thanks for posting the article. It was nice to see you at the event, and congrats again for making the long-list. Historical literary non-fiction has had a difficult time making long-lists and short-lists for prizes, let alone winning, so it was nice to see Bourrie’s book recognized.

Tim

I just found this piece. Thanks so much for writing it.

I have always lived by non-fiction and poetry! Whither, now?