“We are all in this together.”

It’s a phrase often repeated in times of crisis, a common call to arms or for popular solidarity, that leaders have adapted in so many different ways. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s told Americans (at his inauguration in 1933) to pull together since, “The only thing we have to fear, is fear itself.”

In October 1970, after the FLQ kidnapping of a politician and a trade diplomat, Pierre Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act, encouraging Canadians, “If we stand firm, this current situation will soon pass.”

Following the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, George W. Bush said, “We stand together to win the war against terrorism.”

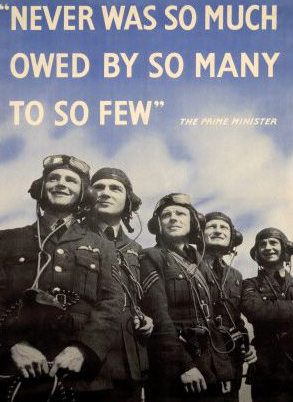

And Winston Churchill’s wartime oratory inspired patriotism and gratitude. His “We shall fight them on the beaches” speech, after Dunkirk, in June 1940, and two months later his tribute to the airmen in the Battle of Britain, 80 years ago this summer, are vivid examples.

“We must never forget,” he said, “never … was so much owed by so many to so few.”

I recently learned from my author friend, Ellin Bessner, just how much Canadians played a role in the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940. More than 100 Canadians were among those “few” whom Churchill applauded, all members of RCAF’s No. 1 Squadron. Those 18- and 20-year-old fighter pilots scrambled daily in Hurricane and Spitfire fighters, against thousands of German bombers and fighters.

In that 53-day struggle, the young Canadians destroyed 29 aircraft and damaged another 35 more. Twenty-three Canadian airmen were killed. There’s even a monument in London, near the Thames, noting one Canadian among “the few”: Flight Lieutenant William Henry Nelson (DFC).

However, in her latest book, Double Threat: Canadian Jews, the Military, and WWII, Ellin Bessner points out, not only does the monument fall short depicting the numbers of “the few,” it also fails to note that F/L Nelson was Jewish. In a Zoom presentation on July 18, she explained to members of the Aircrew Association that as many as 40 of airmen in the Battle of Britain were Canadians, and some of then were Jewish. In part, his family’s choice as immigrants arriving in Canada to change its surname from Katznelson to Nelson, may account for the invisibility of F/L Nelson’s faith. But his deeds spoke volumes about the man’s skill and courage.

“He applied to join the RCAF in 1936, when he was 19,” Ellin said, but was turned down. “He worked his way across the Atlantic … on a cattle boat … and applied and was accepted in the Royal Air Force in 1937.”

In England, F/L Nelson fell in love with British Red Cross worker Marjorie McIntyre. They married quickly – in late August 1939 – as the war was about to begin. In fact, he flew his first operational flight in a bomber on Sept. 8, 1939, the sixth day of the war. With Europe collapsing under Hitler’s Blitzkrieg, in 1940, Nelson transferred from bombers to Spitfire fighters, chalking up several sorties (combat flights) each day.

As the Battle of Britain intensified, F/L Nelson accumulated victories in the air – destroying five German aircraft, damaging two more – and, Bessner said, he became the highest-scoring Canadian Spitfire pilot of the Battle. Then, on Nov. 1, the day after the Battle of Britain officially ended, Nelson was shot down over the English Channel. Neither his plane nor his body were recovered.

“Although the RAF considered Nelson as Church of England, [enlisting as a Christian,]” Bessner said, “his Jewish religion would remain a secret.”

The scarcity of details about F/L Nelson’s career as one of “the few” and the celebration of his extraordinary service lies hidden in the anti-Semitism that Jewish volunteers faced in society and inside the military. Nevertheless, author Bessner pursued Nelson’s story.

His widow Marjorie and their son Bill (who never knew his father) moved to Canada, where she later married Bill McAllister. In 1957, the family returned to Britain. Recently, Ellin tracked down F/L Nelson’s son Bill; she invited him to the Zoom broadcast, and we learned from him about the family secret.

His widow Marjorie and their son Bill (who never knew his father) moved to Canada, where she later married Bill McAllister. In 1957, the family returned to Britain. Recently, Ellin tracked down F/L Nelson’s son Bill; she invited him to the Zoom broadcast, and we learned from him about the family secret.

“Only when my mother was nearly on her deathbed did I learn that my father was Jewish,” Bill McAllister told us from England, in the Zoom cast. “It only made me feel prouder of his accomplishments.”

What author Ellin Bessner makes clear is that 80 years later, some of those who made history or changed it, continue the fight to be included even when their leaders insist, “We are all in this together.”