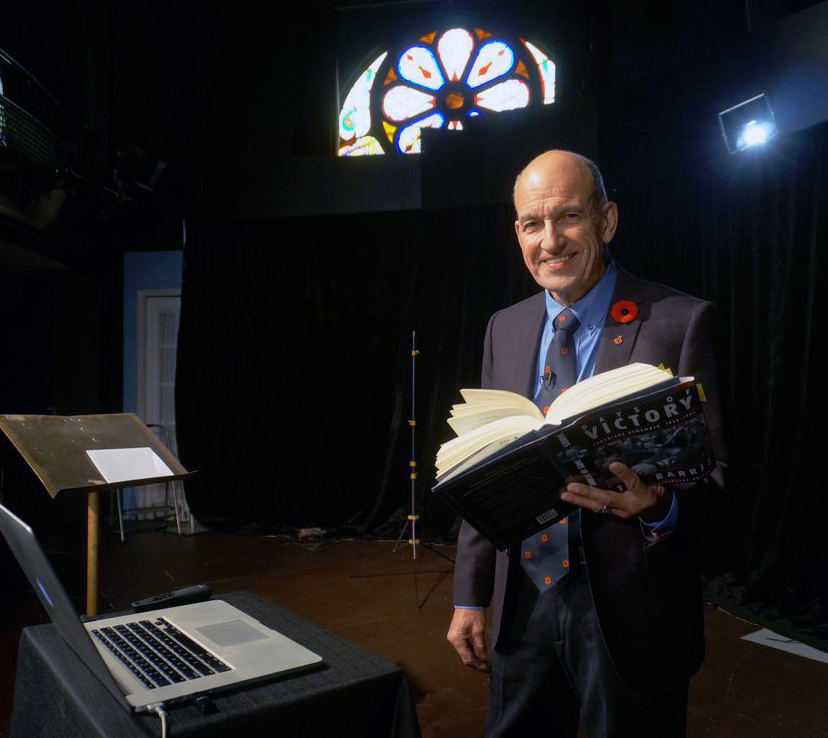

Normally, I’d be feeling a bit nervous. But not this time. Last Tuesday morning, I just walked up a short set of stairs and onto a theatre stage, in St. Thomas, Ont. Unlike many times before, however, there was no audience, just the empty Princess Avenue Playhouse. Then, from the darkness in front of me, I heard the only other person in the theatre call to me.

“Camera’s rolling, Ted,” he said. “You can start anytime.”

And I began my annual Remembrance Day presentation for the Township of Southwold, this year with no audience, just a video camera. Each year, for a decade, I have arrived at the Keystone Complex community centre, in the town of Shedden, near St. Thomas, about 9 o’clock on the Sunday before Nov. 11, to offer a Remembrance talk live.

Remarkably, every year, about 600-700 people have attended. The pandemic has prevented that this year. So, instead, I met St. Thomas-based cinematographer Grayden Laing to record it for a virtual Remembrance Day observance this Sunday.

With Uxbridge’s Nov. 11 event also virtual, next Wednesday, I thought I’d share a unique moment that I’ve offered the Shedden audience. It’s the story of two Canadians who played key roles in the liberation of the Netherlands, 75 years ago this past May. While most acknowledge the end of the Second World War in Europe on May 8, VE-Day, the Dutch do so on May 5.

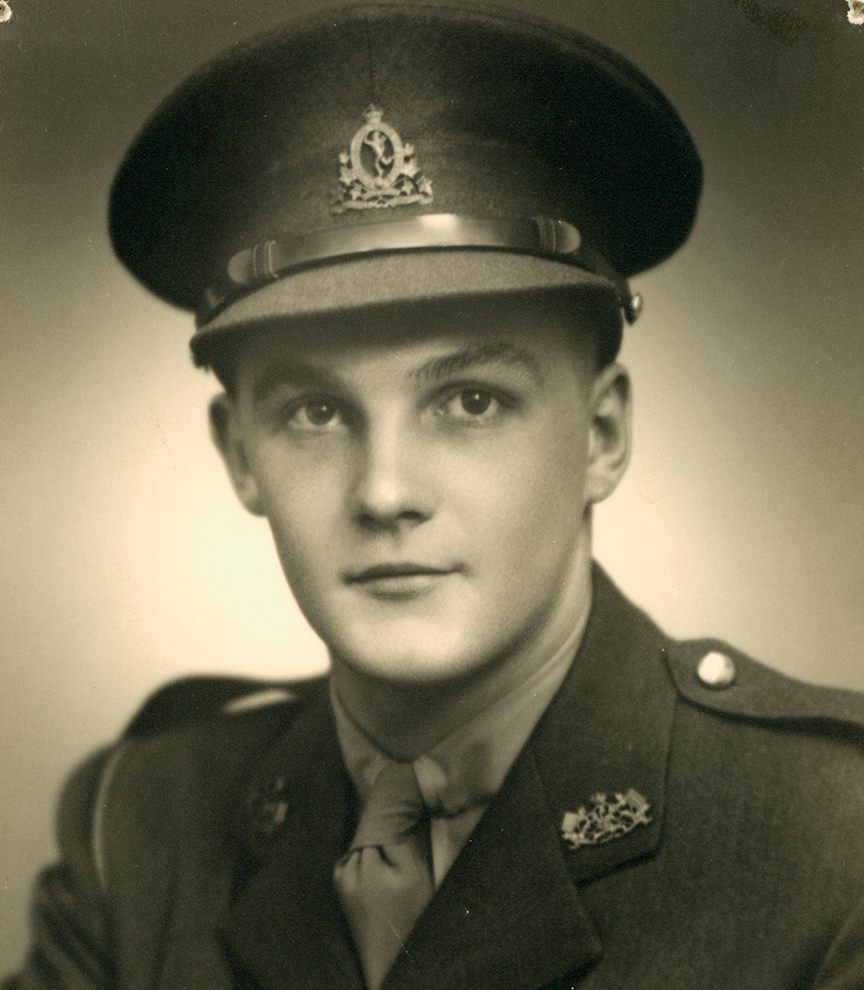

Don Kerr, a WWII veteran who lived in Port Perry, for many years, served in the Canadian Army as a lieutenant in the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals. Landing with the British at Gold Beach on June 6, 1944, he noted that after spending many days waterproofing the signals vehicles for the D-Day landings, Kerr oddly had a dry landing.

“We came off the landing craft and barely got our axles wet,” he said.

Re-joining his Canadian Army comrades, Kerr helped clear German forces occupying French coastal towns, fought across Belgium, and north, liberating towns through the heart of the Netherlands, including the village of Wageningen.

It was there, on May 5, in the tiny Hotel de Wereld, that Canadian Gen. Charles Faulkes sat down at a table to receive the surrender of the German Gen. Johannes Blaskowitz. What most don’t know is how Blaskowitz got there.

On May 4, Lt. Kerr got orders to drive north to Wilhelmshaven, where the Germans had surrendered, but which the Allies had not liberated. They gave Kerr a jeep and a sergeant and told him to drive up the highway and retrieve Gen. Blaskowitz.

“This is the stupidest thing I’ve ever done,” he told his sergeant, “because we were going into no man’s land.”

Suddenly, they rounded a corner and came face-to-face with a German Tiger tank.

“Uh-oh,” Kerr uttered to the sergeant. “This is it. Good bye.” He thought they were gonners. But then the turret flipped open and the German tank commander saluted them as they passed. Eventually, Kerr found Blaskowitz. “I’ve got orders to bring you back.”

“I will not go without my vehicle and personnel,” Blaskowitz said.

Kerr had little choice. He was a lieutenant, Blaskowitz a general. Kerr took the entire entourage. He got proper hell for bringing all of them, but the surrender ceremony went ahead as scheduled at Hotel de Wereld, on May 5.

There’s a famous photo of the official surrender in the dining room at the hotel. The Germans – Blaskowitz and an aide – on one side, and the Canadians – Faulkes and his aides – on the other. There was only one man in the entire room who spoke both English and German. George Molnar, a medical officer from Alberta, was the youngest at the table, and as a captain, the lowest ranking.

“Report for duty early tomorrow,” Molnar was told on May 4. Then, he was driven to Wageningen and dropped off at the hotel. “You’re the official translator,” he was told. And in he went.

Next to Capt. Molnar was the highest-ranking Canadian officer, as well as Dutch Prince Bernhard, and across the table Gen. Blaskowitz, who was old enough to be Molnar’s grandfather. When Faulkes dictated the terms of surrender, Molnar translated and waited for the German’s response.

“I was kept busy that day and didn’t really have much opportunity to reflect on the importance at the time,” Molnar told the Edmonton Journal in 2015. “It certainly was the experience of a lifetime.”

In a way, I’ve always presented Canadians’ wartime service virtually. I was not there. But, in a pandemic, by offering Don Kerr’s and George Molnar’s stories from their reminiscences, I believe it’s especially important to keep their accomplishments tangible and real this Nov. 11.

If interested, my virtual “Liberation of the Netherlands” can be seen at establish media Township of Southwold website beginning at 10 a.m., Sunday, Nov. 8 … and on CHCH TV after 10:30 a.m., Wednesday, Nov. 11.

Thank You for bring this stories to light. I wasn’t there but it is so good to here how it really happened.

Dear Ted

I am reading the article about the Capitulation Signing in Hotel De Wereld in Wageningen, 5 May 1945. The interesting thing is that they brought in a translator – Capt Molnar. At the end of the table was Prins Bernard, who – German by birth – is not mentioned or put into service…