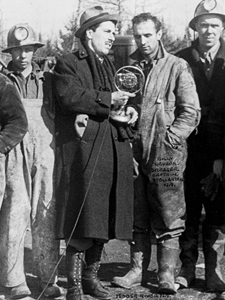

He didn’t look much like a pioneer. But J. Frank Willis sure was. Dressed in tall boots, a long coat and scarf, wearing a fedora – typical of the 1930s – he was a reporter. Hearing news of a coal-mine rescue underway in a remote corner of Nova Scotia, he made his way to a place called Moose River.

There, he found the only available land telephone line and got permission to broadcast from the mouth of the mine. Miners were trapped 50 metres underground and their would-be rescuers had been digging for days to reach them. Willis held his primitive microphone in front of one of the rescuers.

“Here, ladies and gentlemen, is the captain of the rescue team from Stellerton, Nova Scotia,” Willis said.

“Hello Stellerton,” the captain said. “We’re getting’ along fine. We’ll have those men up in a couple of hours.”

Willis’s coverage of the Moose River Mine Disaster in April 1936 made history. Willis had described in five-minute bulletins, every half hour for 111 hours, the progress made by the rescue team. Fifty-eight radio stations of the newly inaugurated Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission (precursor to the CBC Radio Network) carried his unscripted reports.

So did 650 radio stations in the U.S. Then, on April 20, 1936, when the survivors emerged from the cave-in, Willis delivered the news to the world. It was North America’s very first live 24-hour news event.

“I take no special credit for my part on the story,” he said later. “It was my job.”

On the grand scheme of such things as pandemics, vaccines, broken economies and billions of dollars of national debt, writing about the importance of a public broadcaster might not stack up. But it’s a bit like defending long-term care, migrant workers’ rights, and smaller class sizes. If we don’t safeguard some of the foundations of a civilized world, they can easily crumble and fall away when we need them most.

The CBC happens to be under threat from two sides. From the outside, the new leader of the Conservative Party wants to defund the CBC’s digital news services and then sell off the English-language side of CBC TV. Erin O’Toole claims that the CBC is out of control and needs to be reformed.

He says the CBC is “widely regarded as inefficient and far more costly than comparable private sector operations.” I believe what the Conservative leader really means is that he doesn’t like to see CBC TV competing for commercial dollars with private broadcasters in the marketplace.

The only reason the CBC has had to sell time on its English-language television system, is because no federal government – since the CBC was created in 1936 – has seen fit to budget the CBC long-term the way the government does other public corporations. Most CBC presidents, and I’ve interviewed a few of them, have pleaded, “Give us a five-year budget. Then, we can plan better.”

Mr. O’Toole also suggests before CBC TV can be privatized, it must become more “comparable to the private sector in terms of efficiency.” Does he really believe there’s no waste at CTV, Global and other Indies? As a freelance writer with working experience at all those networks, I can assure him, private broadcasters are not models of fiscal efficiency.

The other attack on the now 84-year legacy of public broadcasting in Canada comes from inside. And it reeks of the same sort of push to privatize to save the Corporation. News items have recently appeared – mostly features, presented by CBC personalities – that have been paid for by companies or interest groups as public relations presentations.

The new initiative is called “Tandem” or “branded content.” In other words, they’ve created items that look for all the world like news or journalism, when they are really advertorials for the company purchasing the air time. This violates all the CBC stands for – objective, unencumbered news gathering and reporting.

“Tandem” has so angered some of the icons of the CBC broadcasting stable, that they’ve sent a letter to the CRTC in protest. Former on-air journalists such as Peter Mansbridge, Adrienne Clarkson, Elizabeth Gray, Linden McIntyre and Brian Stewart decry such an initiative as “a clear departure from the mission of Canada’s public broadcaster.”

In 1936, when J. Frank Willis borrowed that old banquet microphone, trekked to Moose River, and reported first-hand to the world on the rescue effort in the rock beneath him, he didn’t pause “for a word from our sponsor.” He did it because the story had to be told, not sold. Nor have the generations of CBC investigative programs – from This Hour has Seven Days, to The Fifth Estate, to Marketplace, to The Nature of Things – paused to consider the sponsor before researching, revealing, reporting and yes sometimes upsetting the status quo.

The CBC helps keep a free society free.