You could almost feel the jubilation from there to here. Video flooded on-air newscasts and social media late Monday. It was nighttime in the Middle East, but the lights on the canal made it seem like day. And the cacophony of maritime whistles and horns blowing seemed deafening. Container ship horns, police boat horns and especially the horns of the Egyptian tugboats on the Suez Canal leapt from every video I watched. One videographer shot images of a jubilant tugboat crew.

“Mashhour is number one!” the sailors shouted.

Mashhour is the name of the dredging vessel that helped clear the tons of sand at the bow and stern of the massive container ship MV Ever Given, that was wedged sideways in the Suez Canal for nearly a week.

On Monday night, a combination of high tide, excavation efforts by dredger Mashhour, and the strategic work of 14 “mighty little boats” of the Suez Canal Authority had refloated the Ever Given. The container ship had blocked passage for hundreds of other cargo freighters and tankers, and it caused economic panic from Alexandria to Wall Street. The Egyptian President, I think, captured the feelings of his fellow citizens.

“Success!” Abdel Fattah el-Sisi said. And he added, “Today, Egyptians have proved they are up to the task.”

Weighing 224,000 tons, and carrying something like 18,300 containers, the 400-metre-long Ever Given is longer than the Eiffel Tower is tall. Most seem to agree that a windstorm, with crosswinds of more than 50 miles per hour overwhelmed the giant ship’s ability to navigate the canal. In any case, when the bow got wedged into one side of the canal and the stern into the other, nothing could pass.

As many as 369 ships had piled up waiting at either end of the canal that links the Red and Mediterranean seas. And some estimates placed the toll for trade lost this week at $9.6 billion per day. So, as the Mashhour crew rightly shouted, they and their tugboat flotilla deserve much credit. Despite much international criticism and urging that experts come from Europe and North America to help, the Egyptians solved the problem themselves.

There was one other occasion, you might be surprised to learn, when sailors and seamanship from halfway around the world – indeed from Canada – offered their services across that same part of the Middle East during an emergency. It happened 137 years ago. In 1884, local authorities in Sudan faced a military uprising. Under Gen. Charles Gordon, British troops in Khartoum suddenly found themselves cut off with rebels closing in.

London called for a relief expedition up the Nile, from Alexandria, Egypt, to Khartoum. Four steamboat captains from the middle of Canada – what was then the Northwest Territories – left their pilothouses and paddlewheeler decks on the Saskatchewan River, to lead the mission up 1,500 miles of some of the most unnavigable river water in the world, to Khartoum.

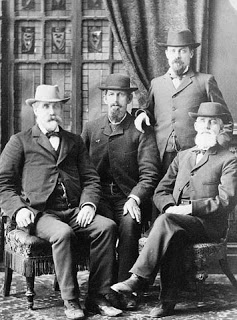

Captains William Robinson, John Segers, Jerry Webber and Aaron Russell accepted $50 per month from the British government to lead two steamboat crews and 400 Canadian voyageurs in smaller boats, and to carry Col. Garnet Wolseley’s relief troops inland. Robinson’s journal reveals fascinating details of the 1,000-mile run from Cairo and Wadi Halfa.

“For at least the first 1,000 miles, rapids are not as bad as ours in Manitoba,” Robinson wrote. And on stretches of the Nile where the water disappeared leaving the boats high and dry, Robinson used a trick he’d employed along sandbars on the Saskatchewan. They dammed up secondary channels of the river to raise water levels in the deepest channel.

Then, everybody went over the side – troops, boatmen and porters – pulling on ropes to line the boats upriver. All well and good on the Saskatchewan River maybe. But not necessarily on the Nile.

“In the early morning,” Robinson wrote, “we would often see crocodiles stretched full length on the sand.”

Over Christmas and the New Year of 1884-85, the four captains nudged their flotilla of steamboats and voyageur boats across the second and third great cataracts of the Nile, toward the final stretch to Khartoum. The rocks proved so troublesome, they even punched holes into the sides of the steel-bottomed hulls of the two rescue steamers Water Lily and Lotus.

In four weeks of hard slogging, the Canadians had traversed half the length of the river, and were within hours of the objective. It was Jan. 30, 1885. Two days earlier, however, rebels had overrun Khartoum and killed the entire British garrison. The rescue mission eventually retook the city and four Canadian captains heralded as heroes of the day.

Like “the mighty little boats” and their crews of the Suez this week, the Canadian sailors of 1885 eventually came through.