It started with registration and Frosh Week in September 1968. I was so eager to attend the school I even lined up at the bookstore to buy a jacket with his name “Ryerson” arched across the back. Three years later, I reached a milestone there when I received the certificate signifying that I had completed all my courses in broadcast journalism. But I returned a few years later, when Ryerson had become a degree-granting institution, completed the makeup courses, and stood in line again to receive my BA in 1976.

“By virtue of the authority granted by the province of Ontario under the Polytechnical Act, 1962, Ryerson has awarded the degree Bachelor of Applied Arts to Theodore Barris,” the document said. Next to my name, a seal with the bust of Egerton Ryerson embossed on the degree.

I thought of that seal, and that bust, Monday morning, as I learned that demonstrators in front of the main gates of Ryerson University in downtown Toronto had toppled the statue of the institution’s namesake.

Several protesters then bashed the metal figure, sprayed paint on it, and covered it with an Indigenous activism flag. And I felt conflicted about seeing the larger-than-life figure of Egerton Adolphus Ryerson dented, stained and disgraced at the Gould Street entrance to the university. This was the home of my former post-secondary education, an experience that had always made me feel proud. This was where I’d studied, been tested, graduated and received my baccalaureate.

Juxtaposed with the embossed bust of Ryerson on my degree, I’ve been reading about the same 19th century educator appointed superintendent of education for Canada West (Ontario) in 1844. Ryerson is credited as the architect of public education… but also of Canada’s Indian residential schools in 1847.

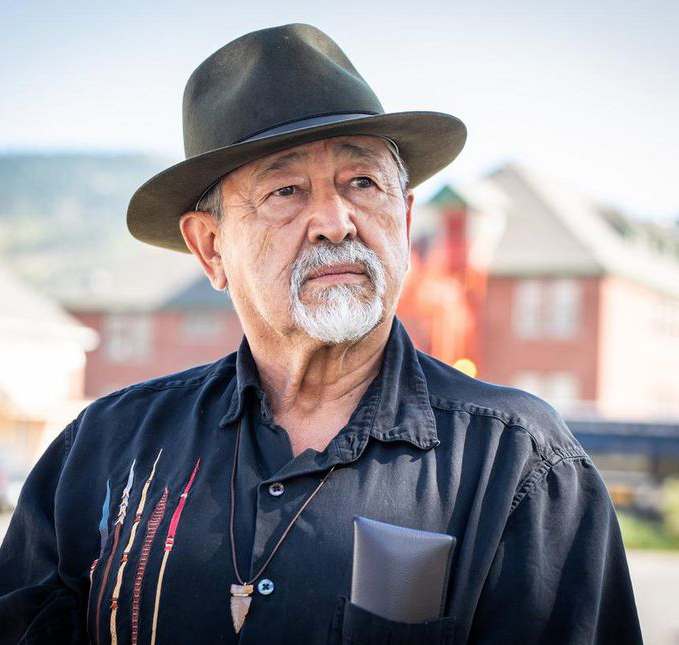

It was on the grounds of one of these facilities where residential school survivor Ron Ignace told Toronto Star reporter Douglas Quan this week, what he was told was the rationale to have older native children dig holes around the school near Kamloops, B.C.

“(They told the older boys) we have some apple trees that we need to plant in the morning,” Ignace said. “Go dig some holes,” holes that allegedly later concealed the bodies of 215 children, who’d died of starvation, beatings, disease or simple neglect of the necessaries of life by the Roman Catholic administrators of the school.

Yes, the namesake of my alma mater had come into his role as Ontario’s education czar claiming that education should be universal and compulsory. But according to Hunter Knight at the University of Toronto’s Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, the Common Schools Act of 1844 did not institute equality of opportunity in schooling.

Her research shows that the Act excluded at least four categories of children. Indigenous children were taken from the families and assigned to the residential system for a dozen years of hard labour and discipline – eradicating any memory of their homes, their families, their language and their cultures. Meanwhile, separate schools established in 1850 for Catholics and Protestants, excluded the children of Black families. In 1862, so-called vagrant and neglected children of the poor were streamed into industrial schools to divert them from imagined lives of crime. And in 1868, the Ryerson model sent children who were deaf or blind to schools where they learned manual trades.

Ryerson envisioned schools as a national development program. His vision was deeply entrenched in colonial, racialized and hierarchical terms, so that Canada would “not be distanced by other countries in the race of civilization,” Ryerson wrote. Knight believes what Ryerson fashioned, however, “amounted to cultural genocide.”

But for people such as myself, who boasted proudly of his degree in broadcasting from Ryerson, there’s a deeper flaw in all this. How could we, who learned the skills of research, investigation and reporting of our world, have completely overlooked the namesake’s ulterior motives in 19th-century Canada West?

Why did none of us, trained to look past the obvious, examine the legacy of Ontario’s guru of education, the parliamentary system which gave its blessing to such marginalizing treatment? Where were our instructors, who may well have turned a blind eye to Ryerson’s colonial and racist agenda in our lectures?

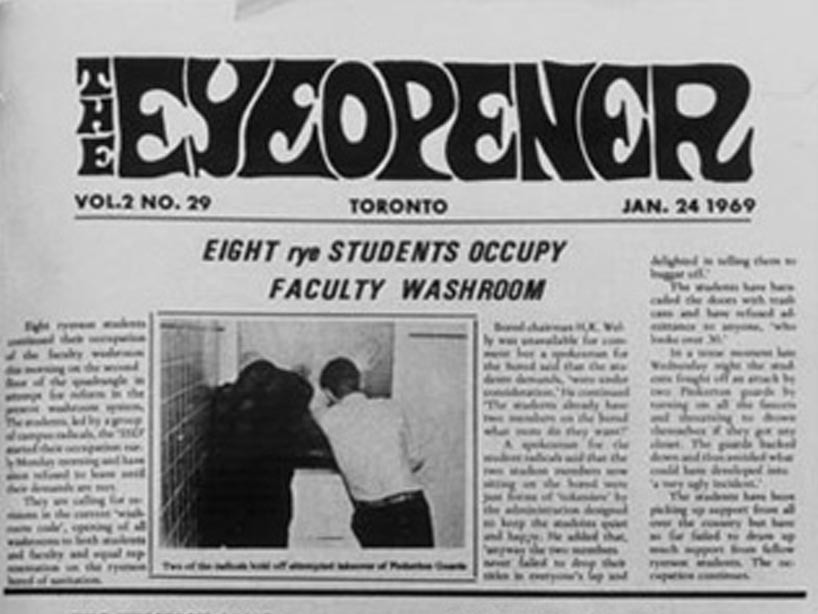

As an undergrad at Ryerson, I reported in the Eyeopener, the Ryerson newspaper. Not once did I consider the history of my school’s founder. I hosted news and current affairs programs on the institution’s radio station CJRT FM and never put a mirror to Ryerson himself.

I graduated from an applied arts program, but never once applied Ryerson’s motto – Mente et artificio (with mind and skill). Questioning deaths at residential schools, exposing the abuse, critiquing the so-called public education system designed by the man embossed on my degree, never crossed my mind.

A toppled statue is the least of our worries.