It’s the last thing my wife and I do each night and nearly the first thing each morning. It’s been that way for nearly 50 years. We turn off the light at night and wake up each morning in sync with broadcasters and their newscasts. At 11:30 p.m., Lisa LaFlamme says:

“That’s it for us at CTV News. Have a good night.”

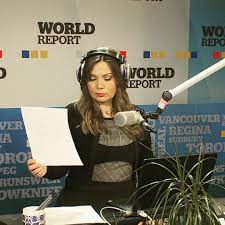

Then, each morning at the top of the hour, we catch Nil Köksal introducing us to, “World Report…” on CBC Radio.

But, we don’t leave Nil at our bedside. She and her newscast stay with us for the next nine or 10 minutes, because we have them on the radio in the bedroom, the bathroom, the kitchen, the laundry room, our offices, or on our cellphones if there’s a corner of the house without a radio close by. Then, we dive into the newspapers – the Toronto Star daily and the Uxbridge Cosmos weekly – to fill in any blanks.

My wife and I readily admit it. We’re news and information junkies. It’s how we feel informed, clued in to the world, aware of the worst and best of what the day offers. There are many like us, equally craving what’s going on at the beginning and end of each day.

But, to our surprise, there are many unlike us, ignoring, even shunning the notion of national or international news. I guess there’s been so much bad news the past year and a half, who can blame those who say, “I just don’t want to know about it”?

You won’t be surprised that psychologists have conducted studies on this. For example, in a 2018 survey, published by the American Psychological Association, scientists learned that more than half of Americans say “the news” causes them stress, fatigue and sleeplessness.

On the other hand, about one in 10 Americans (about 32 million adults) check the news every hour and about a fifth of them (65 million of them) say they stay connected to news feeds constantly. And that was all pre-COVID-19! It’ll be interesting to see how the pandemic may have accelerated people’s shunning the news or craving it.

But I’ve been thinking not so much if people follow the news or not, but how they get news, or what they think is news. Most stunning for me – both as a journalist and a former journalism instructor at Centennial College in Toronto – is how much younger generations believe what they surf on the internet is a reflection of what’s happening. In fact, most of the internet is “views” not “news.”

In a story I followed both on radio and the papers, a reporter asked a woman (a Canadian) how she reached her decision to not to vaccinate herself or her children. “I researched it on the internet,” she said.

“You mean you heard it on radio or online news?” the reporter asked.

“No,” she said. “I get the news on social media.”

Social media are not news sources. None of Twitter, Instagram, TicTok, or even Facebook, can ever be categorized as reliable news sources the way mainstream newspapers, radio and television can. Why not?

As I’ve written often in this column, trained reporters and columnists supply mainstream media with news. Every story, every commentary – whether Liberal or Conservative leaning – is vetted, edited, lawyered and then proofread for objectivity, balanced reporting, and fact-based journalism. Social media are generally unedited opinions, and only rarely challenged for veracity, unless by those with opposing rants.

From as far back as I can remember, members of my family sought out news. I can remember my Greek-born grandfather, each summer morning, departing for his garden. In one hand, his gardening tools. In the other, an unlit cigar and his Greek-language newspaper. Often, the news was weeks old, but he read it faithfully and shared what he’d learned over lunch.

Similarly, my parents – the same way we do – navigated each weekday with news, current affairs, newsmagazines and news broadcasts as the signposts of the day. If Dad was home for supper, it had to be finished by 6:30, because (being former Americans) for my parents the world stopped at that hour as we heard: “The CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite…”

As addicted as my wife and I are to our news and news sources, we’ve recently come to realize that such habits are not automatically handed down – like my grandfather’s reading of Greek newspapers and my father’s date with Walter Cronkite every night.

Recently, with adult family members vaccinated and relatives allowed back inside our house again, one grandson noticed a new radio in the corner of our living room. There was a newscast on.

He listened and asked, “When did you get the news box?”

Appropriately named, we thought.