Halfway through my career teaching journalism, around the year 2008, I received a note of thanks from a young man I’d taught reporting skills, news gathering, copy editing and feature writing, among other things. After graduating from Centennial College’s three-year journalism program, Dharm Makwana had left Toronto, moved to the West Coast and landed a job with the Vancouver Sun.

“Because of you, I feel ready to tackle the challenges of an everyday journalist,” he wrote in his thank-you card. “You contributed more to my professional development than any other teacher I’ve ever had.

“I thank you,” he said finally, “for the impact you’ve had on my life.”

I should have written him a letter right then and there, but I didn’t. Today, in this column, I’m taking a few minutes to compliment my former student on his success in journalism, but also to suggest that his gratitude is misplaced. If I were writing Dharm Makwana today I would first say:

“In fact, the person you need to thank for your opportunity is not me, but former premier Bill Davis.”

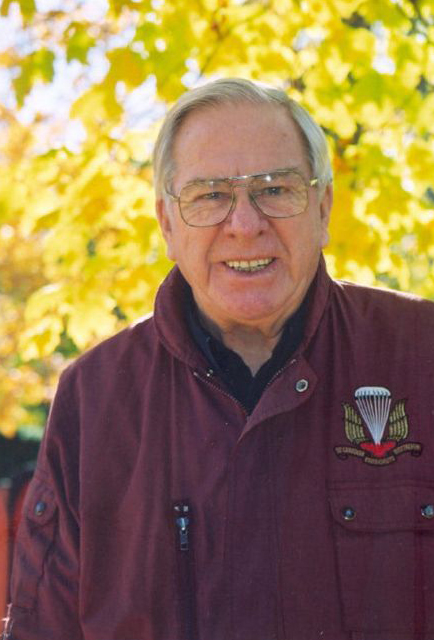

William Grenville Davis, who served a full quarter century at the Ontario legislature – from 1959 to 1984 – winning his Brampton seat as MPP seven straight times, and serving as Ontario’s 18th premier from 1971 until he retired, died on Sunday.

And while historians will long acknowledge his extraordinary run as premier of the province, his cancelling the Spadina Expressway, his rent-review system to protect tenants, his support for building the Skydome, and his leadership patriating the Canadian Constitution and crafting the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, I’d suggest Mr. Davis’s greatest impact on Ontario occurred while he served as the minister of education during the 1960s.

“Davis had a goal to make Ontario a laboratory for all sorts of educational experiments and investments,” Steve Paikin wrote in his biography, Bill Davis: Nation Builder, and Not So Bland After All.

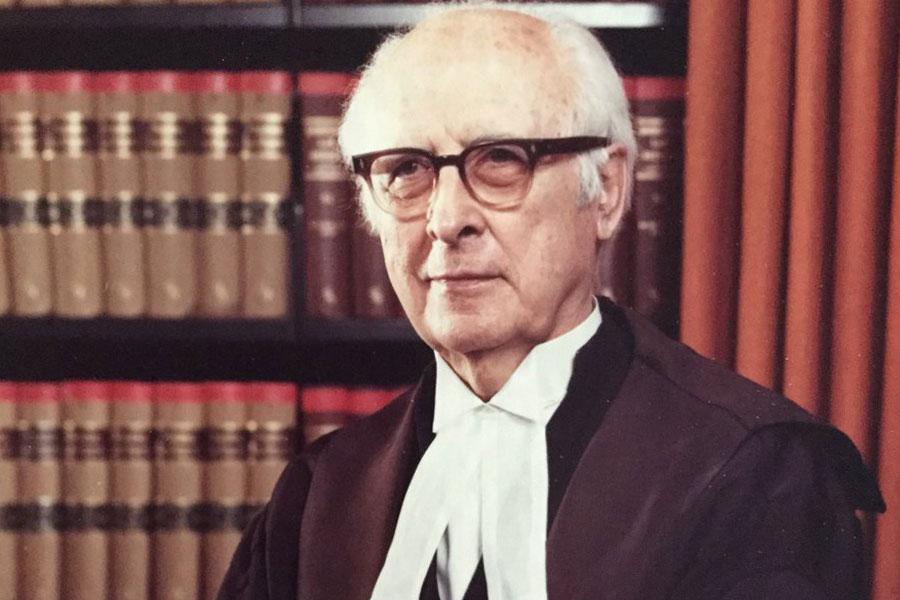

And, in part, tumultuous times in the ’60s precipitated that. The baby boom dictated expansion of education. Ontario’s economy was buoyant, thus so were its budgets. In 1965, Davis commissioned a report on education, chaired by Supreme Court of Canada Justice Emmett Hall and former school principal Lloyd Dennis.

Among the report’s 258 recommendations was a proposal to establish alternatives to university education in Ontario. On May 21, 1965, Davis unveiled Bill 153, to establish 20 colleges of applied arts and technology.

“Considered a revolutionary development,” wrote Paikin, “they would offer a new vocational training option and lead much more directly into the labour force.”

In other words, they offered high-school graduates and others the chance to learn an employable skill not by thinking about it, writing essays about it, theorizing about it, but instead by doing it!

The first of the 20 community colleges – Centennial College – opened in the fall of 1966 (the year before Canada’s Centennial) to 430 full-time day students. More than 40 per cent of them came from nearby high schools, another 14 per cent were adults over the age of 19 who’d been out of school a year; there were also 160 students taking part-time night courses.

(By the time I taught at Centennial, between 1999 and 2017, it had grown to four campuses, 18,000 full-time students and another 20,000 part-timers.)

That’s not to say that then education minister Davis let Ontario universities wither. Just the opposite. Of Ontario’s current 23 universities, six of them owe their origins to Davis’s time as Ontario’s inaugural minister responsible for university affairs.

Even some of Bill Davis’s strongest political opponents, Bob Rae among them, gave Davis full marks for his focus on education. “(Davis) built an extraordinary infrastructure for education in the province,” Rae told Paikin. “He did so without any deep sense of narrow partisanship, and he did it with a broad sense of what was good for the community as a whole.”

I remember student Dharm Makwana distinctly from my time as journalism instructor at Centennial. He’d studied political science at Wilfrid Laurier University. He knew his subject. But he didn’t have the skills to pitch a political story to an editor, find its sources, get succinct interviews or bash out a publishable story by deadline.

By the time Dharm finished our courses, however, in addition to the basics, he led the pack in audio-visual reporting. That’s how he landed his position at the Vancouver Sun. I maintain he’d never have found his calling with only his Laurier degree. He needed the learning-by-doing skills Centennial gave him.

“I’ll always be grateful for the impact you’ve had on my life,” Dharm wrote in his thank-you note to me in 2008, “and will have on my future.”

I cannot think of a more appropriate epitaph for Bill Davis, Ontario’s education minister of the century.

Hi Ted,

I really enjoyed your piece — glad to see the focus on Davis’ education legacy. If you are interested in Hall Dennis, you might be interested in this.

https://www.mqup.ca/hall-dennis-and-the-road-to-utopia-products-9780228006336.php

Josh Cole

Oops. Here is the actual link! https://www.mqup.ca/hall-dennis-and-the-road-to-utopia-products-9780228006343.php?page_id=73&