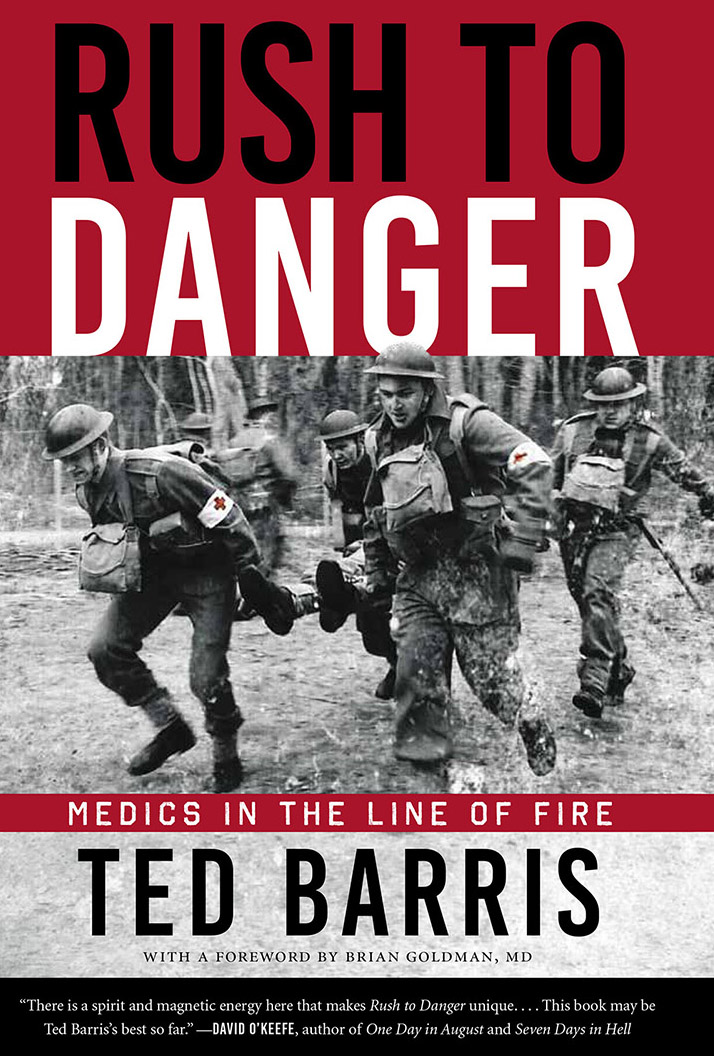

He is a veteran. He is the grandson of a veteran. As important to me as anything, however, Klaus Keast, a total stranger, has found a connection that’s brought us together unexpectedly. He recently wrote me an email requesting an autographed copy of my 2019 book Rush to Danger, about military medics. But in addition, he asked if I could acknowledge the military service of his mentor.

“He (was) a Jewish medic, who not only served in WWII,” Keast wrote, “but he also had to fight to be involved in the war effort when initially refused by (anti-Semitic) recruiters.”

I thought, how appropriate that a man of Jewish faith fought prejudice in his own Allied army to be able to serve in the Second World War against the Nazis. He also served in defiance of the Holocaust. And finally, rather than choosing to take lives, he chose to preserve them – as a medic.

“And he’s featured on the front cover of your book, Rush to Danger,” Keast wrote.

I had no idea that one of those four medics on my book dust jacket was Keast’s mentor. And, since I have not yet communicated further with Keast, I still don’t know the Jewish medic’s name. But in the last few days, since I received Keast’s note, I’ve kept pinching myself that his appearance on the cover of my book is purely coincidental.

The photo was chosen randomly by the art designer at my publisher’s office. It shows four British Army medics carrying a wounded soldier to safety in Norway in 1940. I applauded the art designer’s choice, but had no idea who the medics were until Keast emailed me, last week.

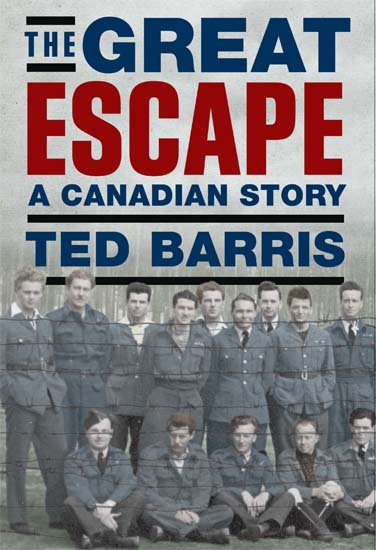

And this is at least the third time an image chosen for my books, coincidentally revealed more than I’d ever anticipated. Shortly after my book about The Great Escape was published in 2013, I received an email from Rob McKay, an air-traffic controller in Vancouver.

He’d seen a photo in my book depicting members of the Royal Canadian Air Force imprisoned inside at the Stalag Luft III German POW compound in Poland. They’d formed one of many inside-the-wire baseball teams.

“One of the prisoners pictured in your book,” McKay wrote, “was my Great Uncle Tom (Tommy) Jackson.”

I opened a copy of my book, The Great Escape: A Canadian Story, and there behind the crisscrossed bats in the photo was a smiling, 29-year-old Canadian bomber pilot, in 1943. To help pass the time of wartime incarceration, the men played sports (which helped disguise construction of the escape tunnels used in the escape March 24/25, 1944).

But McKay’s email painted an even more vivid picture of his great uncle.

“One Saturday evening, at my mom’s home in Abbotsford, years after the war, during a hockey game, no less, Uncle Tom started talking about the war. He was the pilot aboard a Halifax bomber shot down over northern Germany,” McKay wrote.

“Uncle Tom thought his entire crew got out before he bailed out. He later learned that the tail gunner had forgotten his parachute. He knew if Tom found him, they would both try to use one parachute and would both die. So, he’d hidden in the back of the plane and died when the bomber crashed.”

It was a story not found in my book, but which I’ve shared with audiences for nearly a decade.

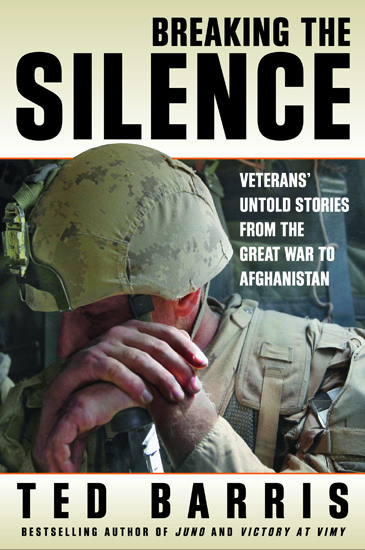

Even more coincidentally, when I chose the cover for Breaking the Silence, my book about meeting veterans and how they’ve battled their PTSD demons, I tripped over a photo taken during Canada’s NATO mission in the Afghanistan War. It showed a Canadian soldier inside a troop transport.

First, I acquired rights to publish the photo and then searched the Canadian Armed Forces system to get permission from Corporal Chris deBeaupre to use his picture. He quickly said he’d be honoured.

By October of that year, I was on the road, speaking about the book and its hundreds of stories from WWII, the Korean War and Iraq and Afghanistan. In five weeks, I was interviewed about a hundred times. But none of my interview sessions came close to a chance encounter that November.

Following one of my talks at a Toronto suburban bookstore, a woman in the audience caught my attention. I introduced myself and so did she.

“I’m Sandy deBeaupre,” she said, “my son is on your book cover.”

There are some who claim such encounters are fate. I tend to think they’re coincidental. But as I absorb my most recent email exchange with the Klaus Keast, whose mentor somehow ended up on the cover of my book, I can’t help but think I didn’t so much choose these images. They kind of chose me.