The performance had gone on through a first act. An ensemble of jazz singers had sung their hearts out. A quartet of musicians played with enthusiasm we hadn’t seen in months. Our daughter sat with us watching, listening. The energy in the club seemed electric. Then, in the second act, she was invited to the stage to sing her part in a tribute to American composer Stephen Sondheim. But before singing a single note, Whitney Ross-Barris looked out over a nearly capacity room and paused with a big smile.

“This is just the most exciting thing,” she said, “to be back singing in front of an audience.”

That she sang with gusto and verve was no surprise to us – her mother and dad. But like all the other performers that night at the Jazz Bistro in Toronto, last Saturday night, somehow her delivery had extra jump. Everybody seemed to rise to the occasion and put on the performance of a lifetime.

And I was reminded of the Canadian rock band Chilliwack from 50 years ago. A chorus lyric in their 1971 hit-song Rain-O said it all: “If there’s no audience, there just ain’t no show.”

Last week, I travelled to Alberta to fulfill a couple of long-standing commitments to present history talks publicly. My first stop was Camrose, a community about an hour’s drive southeast of Edmonton. There, at the invitation of Blain Fowler, publisher of The Camrose Booster newspaper, I took to the stage of the 102-year-old Bailey Theatre.

It’s been closed through the entire pandemic. But Fowler wanted to revive the tradition of staging Remembrance events at the theatre and I’d agreed to come and speak. (All audience members had to prove full vaccination before entry.)

Just like my daughter, I commented on the thrill of offering a public performance after two years of lockdowns. One of the patrons who approached me after the show captured the moment. “I think this is what normal feels like,” he said.

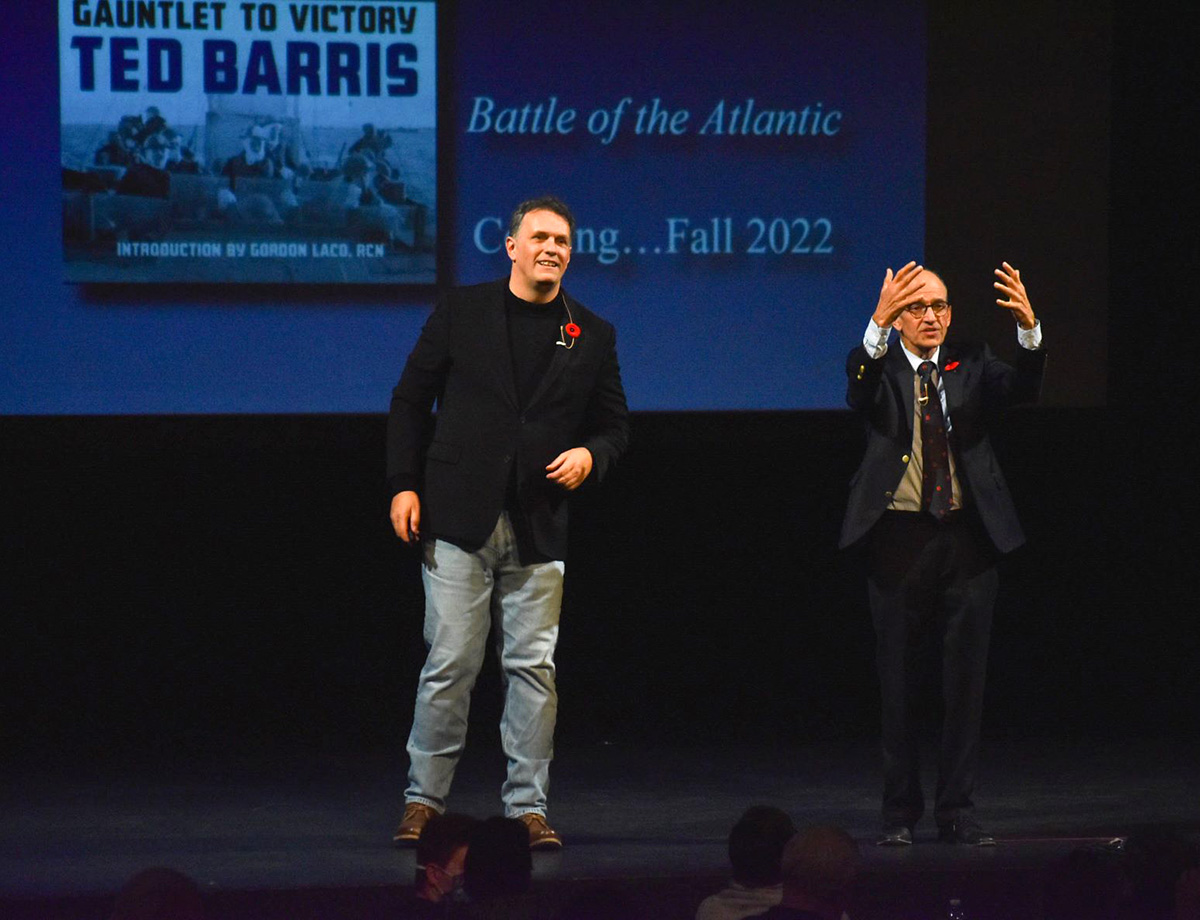

Two nights later, I joined fellow historian David O’Keefe on stage at Festival Theatre, in Sherwood Park, a satellite community east of Edmonton. Two years ago, when O’Keefe and I presented a “History Storytellers” evening recounting the experiences of Canadians on D-Day (75 years later), we promised we’d return in 2020 for a second history night recounting the Canadians’ liberation of the Netherlands in 1944-45. COVID killed that show.

But David and I eventually delivered on the promise of performance, last Friday night. As we were introduced by mutual friend and Canadian Forces veteran Tim Isberg, David and I could feel the buzz of the audience mounting. We stepped on stage to receive quite an ovation.

I thought, “They’re really applauding that they’re enjoying being at an event … any event.”

“Truth is we’d have walked all the way here from eastern Canada,” O’Keefe said out loud.

Two years of static Zoom events have made us appreciate live, in-person appearances even more. I thought comedian Stephen Colbert summed up what returning to the public eye felt like. Back in the spring, the star of The Late Show with Stephen Colbert returned to the Ed Sullivan Theater in New York. The pandemic had forced its closure for 460 days.

When CBS announced its re-opening in June, Colbert fussed over what he would say in his opening monologue. “So, how ya’ been?” he blurted out.

Toward the end of the “History Storytellers” evening at the Festival Theatre in Alberta, last Friday night, my colleague David O’Keefe and I asked for the lights up in the theatre to take questions.

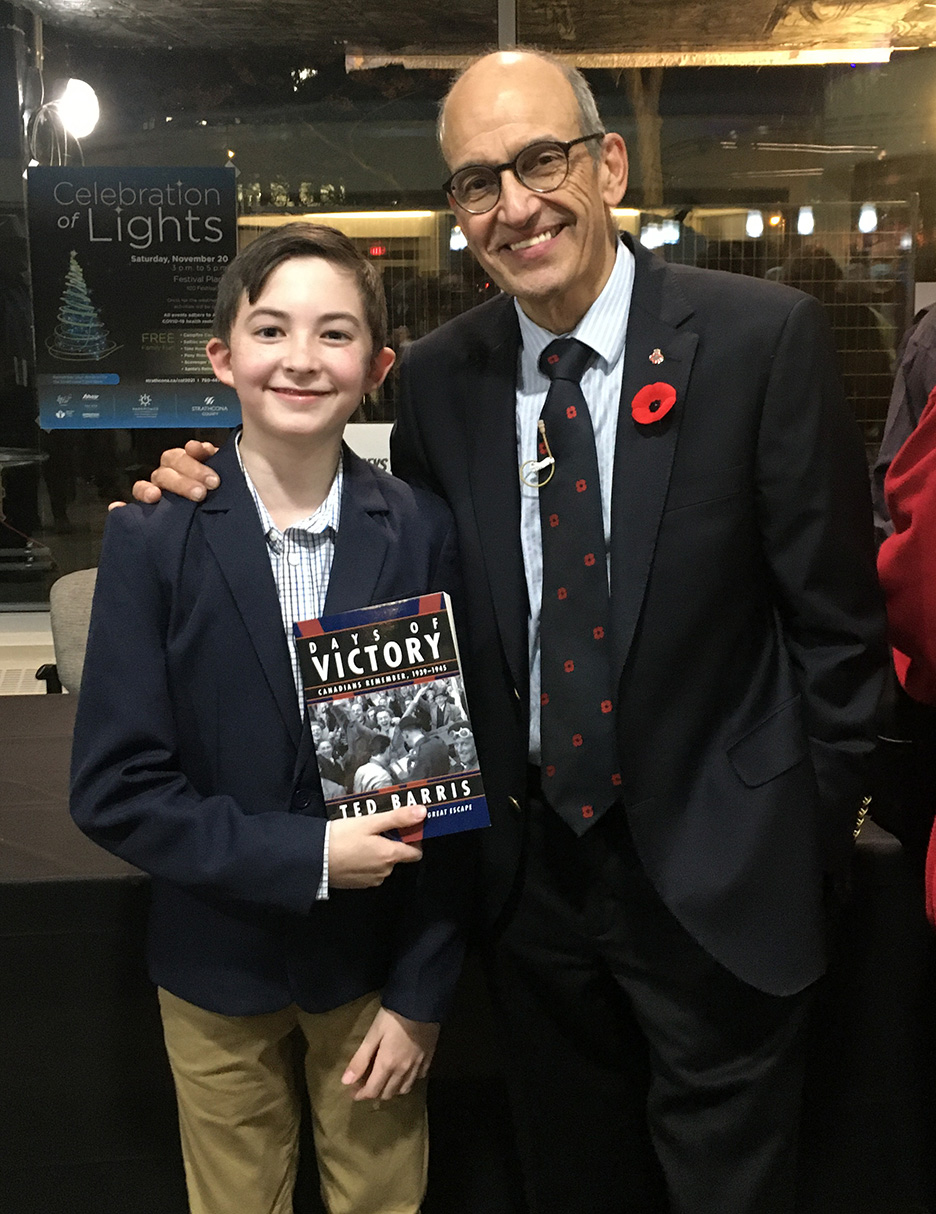

The final question of the night was posed by probably the youngest member of our audience. Sitting next to his mother, 12-year-old Chase Mardres thrust up his hand.

“Mr. Barris, can you tell me about the most emotional part of writing your book Days of Victory?”

“Sure,” I said, “but my answer probably won’t be very satisfying.” I told Chase and the audience that I had co-authored the first edition of the book in 1995 with my father Alex Barris. We had each gone out across the country – Dad to the East, I to the West – interviewing veterans about their wartime experiences.

Then, we sat in a room with all those tapes and files and photographs and wrote the book. “When the book was published, seeing our names side-by-side on the cover, for me that was emotional to share the moment with my father, my mentor, my best friend,” I said. Chase came up to me afterwards and thanked me for my answer.

“What a privilege to be in an audience,” he said, “witnessing your stories.”

“No, Chase,” I suggested. “Until the pandemic came along, we’ve taken the opportunity to speak in public for granted. The privilege of telling those stories was all mine.”