My parents, both U.S.-born, often took my sister and me on road trips back across the border in the 1950s and ’60s to visit our American cousins in the summertime. To help break the monotony of the drives to New York City, our parents often found amusement parks for us to visit along the way. One I’ll never forget was in the Adirondack mountains of upstate New York.

“Frontier Town!” announced the big red sign at the park’s entrance. And the marketing subtitle declared, “Where the Wild West begins.”

Inside we toured the massive railroad station, sawmill, the church, the requisite hotel and saloon and, of course, the jail. The place was crawling with tourists; Frontier Town bragged it had 3,000 guests each day on the weekends. Among the big attractions my sister and I enjoyed were all the “outlaws” re-enacting shootouts on the streets and robbing the stage coach in which we toured the park.

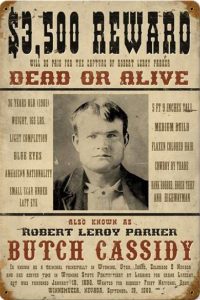

Odd, but what I remember most about Frontier Town, was the look of the signage. You know, the lettering – its fat, blocky letters with spikes sticking out of the sides – identifying The Saloon, The Livery Stable, or on the Wanted posters outside the jail.

Even when I watched all those westerns on TV – Gunsmoke, Maverick, Have Gun Will Travel and The Rifleman – I always associated that OLD West lettering with the real Old West, as in the American West in the 1800s.

Well, when I researched I learned that the OLD West print type was pretty much a Hollywood invention. In fact, Walt Disney (who created much of the 1950s mythology about the Old West on TV and in “Frontierland,” his Disneyland cowboy theme park) actually stole the lettering style from, you guessed it, Frontier Town amusement park in upstate New York.

Old West script, if one checks it out, comes from a frontier reality; in order for signs to be legible, the lettering had to be big, bold and obvious for cutting into wooden signs posted outside buildings; and the spikes out the side, some suggest, were added for effect, like spurs on cowboy boots.

I’m discovering, like the Old West font myth, that we’re likely to believe whatever the handiest and quickest media tool can give us, even if it’s wrong. Actual history is fading, being lost, because we’re limiting our understanding of history to whatever parts of it have been digitized.

Too many moments of history or artifacts from it – from a time before the world wide web and social media – have fallen through the cracks. Indeed, anything hard copy – as in letters, documents, actual photographs – is physically too complicated, too expensive, too time-consuming, (dare I say too passé) to consider historical.

By example, I’ve been trying to find a photograph of a wartime Canadian news correspondent, a reporter named Jack Brayley, who served as the Canadian Press (CP) news bureau chief in Halifax during the Second World War.

Brayley was relentless reporting the facts about news events in Atlantic Canada during the war. To skirt government censors, when reporting to his editors, he even developed code words to disguise military activity he’d witnessed.

Anyway, my search for a photo of Brayley led me to CP’s head office in Toronto. The single archivist I reached by phone told me that all such photographs had been boxed up and sent to a warehouse. She could only supply a picture if it had been digitized. Brayley’s had not.

“Can’t someone search the warehouse box files?” I asked.

“Once, we could,” she said. “But our archive staff that was once 600 (across Canada) is now just two.”

I thanked her for the reality check, and realized if Brayley’s photo existed in hard copy anywhere, it was likely lost to history because someone (who had no idea who he was) figured the picture of a wartime bureau chief in Halifax wasn’t important enough to digitize. And Brayley’s image was likely lost forever.

And I remembered the final scenes from the movie Raiders of the Lost Ark, when Indiana Jones, the Harrison Ford character, asks the U.S. security guy if the Ark he’d recovered was being researched and catalogued.

“We have our top man working on it, right now,” the security guy says.

And the film cuts to a box (with the Ark) – identified only as “Top Secret. Army Intel.” – being rolled on a trolley across the floor of a vast, nondescript warehouse. As the camera pulls back, the warehouse worker and trolley disappear around the corner of a pile of boxes extending as far as the eye can see, every box marked exactly the same.

The print on the box, by the way, looked like it was right out of Frontier Town.

Hey Ted, I actually did a little research about the font after you asked me, and didn’t get too far so I didn’t report back to you. I only vaguely remember going to Frontier Town, but what they’re doing in Tombstone is pretty much the same, and just as hokey. (I’m actually finally working on that blog today.)

Interesting and frustrating about the historic records, lost only because nobody wants to bother. I have long thought that despite being in a generation in which everything can be and is recorded on our phones, computers and tablets, we’ll probably be the LEAST recorded, as the methods of digitization change and nobody has the technology to read, listen to or view them – like VHS, Beta, floppy discs, those little mini discs that used to go in our cameras… the list goes on. Soon they’ll all be in that warehouse with the ark. Or in landfill. At least your books will still be around!