He was the only source I’ve ever interviewed who intimidated me. And it wasn’t his personality or his manner that scared me. In fact, he proved to be among the most gracious, easy-going people I’ve ever interviewed. We met over the telephone back in the winter of 1976, and I began our conversation very formally, addressing him as “Mister.” And he immediately broke the ice with his first response.

“Please. Call me Joey,” he said. “Everybody does.”

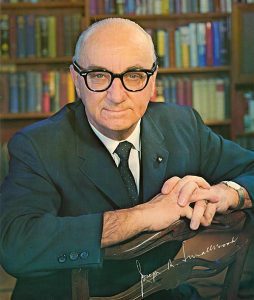

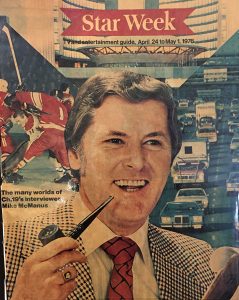

“Thank you, Joey,” I responded, and I began my first and only interview with a Father of Confederation, the then recently retired premier of Newfoundland and Labrador, Joseph R. Smallwood. At age 76, he’d stepped down as premier only four years before. But he’d actually become Newfoundland’s first premier in 1949, when he successfully campaigned for the former Dominion of Newfoundland to join Confederation that year. That’s why he’s officially a Father of Confederation. And that’s why I felt so intimidated. I was a youngster by comparison, just 27, and hired on as a story editor at TV Ontario to prepare interview material for the host of a show called The Education of Mike McManus.

It turned out – in many ways – to be the education of Ted Barris. In those days, about 25 years after television had arrived in Canada, broadcast journalism relied on some very basic foundation blocks. The notion of newsmakers and celebrities appearing on TV had become pretty common. Movers and shakers were accessible.

Indeed, I could pick up a telephone and track down Joey Smallwood, the former premier of Newfoundland and invite him to an interview show in Toronto. The tough part, as I learned from story-producing for Mike McManus, required gum-shoe journalism – travelling to libraries, reading manuscripts, tracking down audio, video and newspaper clippings and interviewing peers (both friends and enemies).

Then, with all that data in hand, the show required that the story editor – me – prepare a written document for interviewer McManus. Mike called it “a brief.” But those 30-or-so pages I wrote provided lengthy background on the subject, a concise biography, quotations accredited to the source, criticism from contemporaries, do’s and don’ts for the interviewer, and specific questions that would draw out the source.

Each brief was no less than 5,000 words of original writing (that’s the equivalent of about six and a quarter Barris Beats). Each story editor on the show had to prepare two briefs per week (about 12 Barris Beats). Then, each story editor had to be there when the guest(s) arrived, warm them up with conversation, and escort them into the studio to meet Mike McManus for the on-camera interview.

When his interview was over (we did two half-hours with him), Joey Smallwood commented, “I think getting Newfoundland into Confederation was simpler than getting ready for this interview.” I took that as a compliment.

Between the fall of 1975 and the spring of 1976, as story editor I prepared 32 briefs for host McManus on subjects as diverse as franchising in Canada, the anatomy of a political convention, Canadian volunteers in the Spanish Civil War, career counselling, the family farm, winning and losing in pro sport, profit sharing, adversity and survival on the Canadian Prairies, Canada’s polar frontier, government secrecy and the freedom of information act, UFOs in Canada, as well as profiles of well-known Canadians such as architect Arthur Erickson, historian James Gray, novelist Hugh Garner, evangelist Charles Templeton and political strategist Dalton Camp, to name a few.

Each was an education in research, concise writing and interview preparation. Ultimately, a successful TV interview depended on Mike McManus’s skill to absorb each brief, understand the mind and personality of each guest and deliver all of that successfully to a television audience. His instincts and our digging generally delivered good television five nights a week.

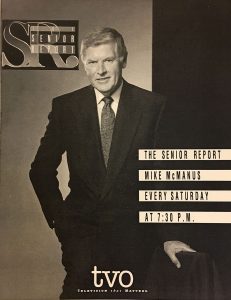

Last week, I attended a memorial for Mike McManus; he’d died on June 27 after illness at the age of 91. At the ceremony I met Barbara Miles, Mike’s wife. She remembered the effort that went into each interview her husband conducted on-air. “He’d come home on the weekend with an armful of briefs. For two days we never saw him; he immersed himself in your research.”

I said that I couldn’t begin to tell her how much I had learned from the experience. Mike McManus’s expectation for us to be the best at what we did, and ultimately the demands of creating coherent, memorable TV interviews helped us all become better communicators.

“You know that expression, ‘I could write a book,’” I told Barbara at the memorial. “I wrote 32 books that season. And in a way, each week, Mike published them on-air at TV Ontario.”

Ted, I just want to express my brief interaction with you dad in the early 1950s when as a 15 year old I took apart the basement stairs in your Agincourt home so your dad could get his piano into the basement. He was very sceptical about me when my dad dropped me off to do the work but gave me lots of praise when I got everything back together. Something that the son of a new Canadian really appreciated and never forgot especially since he was such a celeberty, or soon to become one.

I’m a history grad from Carleton and a long time neighbour of Allister Sweeny that you might know. I’m empressed with all your military stories and your interesting media interviews at this time, a chip off the old block as they say.

Best regards, John Almstedt, Ottawa