He stood at the lectern in front of hundreds of us. A lit cigarette dangled from his left hand (they were allowed indoors back then). He spoke almost entirely without notes, as if his words were a credo he’d crafted over years until the message came out as his own. I’m paraphrasing now, but here’s what this man from Quebec said on stage at the University of Toronto’s Convocation Hall that day:

“We are heirs to a fantastic adventure – an early America that was almost entirely French,” he said. “We are heirs to an obstinate group which has kept alive that portion of French America we call Quebec…”

The year was 1969. I’d sat mesmerized for the better part of 90 minutes inside Convocation Hall, listening to the man who wanted to lead Quebec out of Canada. René Lévesque was an avowed separatist, but his argument about the survival of French culture, language and religion I found so compelling I nearly became a convert to his argument. “This is how we differ from other men and especially other North Americans,” he concluded. “This basic difference we cannot surrender…”

René Lévesque founded the Parti Québécois in the 1960s (when I first heard of him), and he openly campaigned to lead his home province out of Canada, to separate from Canada. By 1970, his PQ had garnered 25 per cent of the vote. By 1976, it had become the provincial government and unveiled controversial Bill 101, whose stated goal was to make French “the normal and everyday language of work, instruction, communication, commerce and business,” and one day to become the official language of a distinct nation landlocked inside Canada.

Because I had witnessed his oratory in person and listened to his arguments for years, I felt great sympathy for his efforts to preserve French language and culture. He made sense, even if I didn’t support his goal – to make Quebec separate.

In contrast, I offer the recent rhetoric of Danielle Smith, the newly installed Premier of Alberta who wishes to affirm the authority of the Alberta Legislature to refuse provincial enforcement of specific federal laws or policies “that violate the jurisdictional rights of Alberta.”

During her campaign to succeed Jason Kenney as leader of the United Conservative Party (and thereby become premier) in Alberta, Smith claimed that “the majority of Albertans are frustrated with … attacks on Alberta by our federal government, and want effective action to deal with the ‘Ottawa Problem.’”

Smith’s so-called Sovereignty Act sounds an awful lot like a prelude to separation, but she makes none of the compelling arguments that Lévesque did 50 years ago on that stage at the U of T. If all she can conjure as the demon is an “Ottawa Problem,” and all she can offer as antidote is a provincial law to allow Alberta MLAs to vote freely on a “special motion” that Ottawa is violating Alberta’s rights, I think she’s skating on pretty thin ice.

Eric Adams, a University of Alberta professor of constitutional law, says her Sovereignty Act “is of dubious constitutionality.”

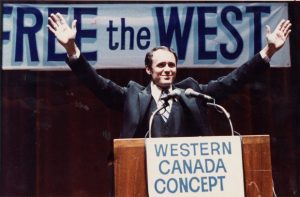

I lived and worked in Alberta during the rise and fall of the WCC, the Western Canada Concept party. Founded in 1980, its objective was to take the four Prairie provinces out of Canada and join them with British Columbia to form a separate country. The party’s leader until 2013 was Doug Christie, a right-wing lawyer who was also known as a Holocaust denier.

In 1983, the WCC nominated 18 candidates in a B.C. election, garnered about 14,000 votes or about 0.86 per cent of the popular vote. Founded on little more than discontent with Ottawa, the WCC then quietly disappeared.

I also remember the last time we felt that the future of Canada as a nation was in peril. It was the Quebec Referendum of October 1995. The forces of Quebec sovereignty had managed to force a provincial vote on the matter.

The “Yes” forces wishing to provoke a sovereignty vote in Quebec had the momentum. The “No” side seemed to be fading. On Oct. 27, 1995, three days before the referendum, thousands of Canadians travelled to Montreal for the “No” rally at Place du Canada. There, we listened to the eloquence of Quebecers who wanted to give Canada one more chance.

I drove to Montreal that day with my wife and one of our daughters. The other had a sports tournament she was obliged to attend and wrote on a Post-It on my bathroom mirror: “Please save my country.”

Unlike the tantrum of an Alberta premier, my daughter’s sentiment rang with the passion and sincerity of a Quebecois orator hoping to preserve his identity and culture.