I almost missed her. I’d finished a presentation to the Tillsonburg military historical club. In fact, I thought I’d answered all of the questions from the audience. Then, I noticed a woman in the back row with her hand raised. Even when she stood, I could only see her head and shoulders above the seated audience. Diminutive though she was, however, her voice was strong.

“My father was in the Battle of the Atlantic,” she announced. “He went down with HMCS Shawinigan. All hands were lost.”

As painful as her words felt, Betty Lou Wallington spoke without losing her composure. She explained that her father, Spencer Wallington, had enlisted in the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve (RCNVR) almost from the moment Britain and the Commonwealth declared war on Germany in 1939. She said her dad told the recruiter at the enlistment office he was colour blind.

“No problem,” Betty Lou claimed the recruiter told her dad. “Stokers don’t need to see at all to work in a warship engine room.”

Nevertheless, as the ship hand most responsible for maintaining Shawinigan’s steam engines, boilers and gauges, Leading Stoker Wallington, needed his engineer’s papers and full basic training in the Navy to serve in such a warship. Nearly 100 men in her crew depended on that skill.

And yet, should the ship be torpedoed by a U-boat, LS Wallington and most others in her engine room would have little or no chance of surviving a sinking corvette.

“Nobody knows for sure what happened to Shawinigan,” Betty Lou Wallington told the audience in Tillsonburg. “She was sunk in November 1942 escorting a ferry to Newfoundland.”

Indeed, very little is known about the German U-boats’ invasion of the Gulf of the St. Lawrence River that year. The Canadian government was so caught off guard, that it censored all reports, news stories and broadcasts about U-boat attacks in the Gulf. What Betty Lou didn’t know is that her father’s warship was struck by a German GNAT torpedo – an acoustic weapon designed to home in on the sound of Allied warship propellers underwater.

Shawinigan’s crew, including her father, probably never knew what hit them. It happened that fast.

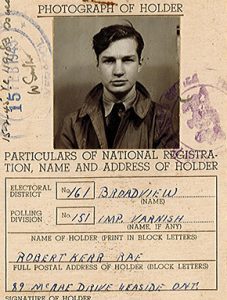

What is also little known about that chapter of the Second World War is the job that merchant navy telegrapher Robert Rae fulfilled in the Battle of the Atlantic. A teenager when Canada declared war on Germany on Sept. 10, 1939, Rae tried to enlist as a fighter pilot. RCAF recruiters told him he didn’t have enough education. So, his next choice was not so obvious.

“We saw all these stories of these men in the merchant navy coming back to Halifax after having their ships shot out from under them. Two weeks later they’d back out to sea. They were my heroes.”

For the majority of the war, Rae served as a radio operator aboard merchant ships of the Canadian Park Steamship Co., delivering the freight and fuel that would keep both the British military and 41 million civilians alive.

The merchant navy, known as “the fourth arm of Canada’s fighting forces,” completed more than 25,000 transatlantic trips even though merchant sailors faced a one-in-eight chance of being killed, wounded or captured. Rae’s son Steve told me that when the Canadian government denied merchant sailors “veteran” status at the end of the war (the government claiming they were civilians hired by private shipping companies, not military), his dad was despondent.

“He took his medals, threw them in a box and hid them in a drawer,” Steve Rae told me.

But in the 1980s, challenged and invigorated by his comrades, Robert Rae began campaigning for the rights due all those who’d served in Canada’s wartime forces. The merchant mariners petitioned Canadian senators, staged hunger strikes, and in 1994 finally won the right to be called “veterans.”

That year, for the first time ever, a Canadian Merchant Navy sailor was allowed to place the Remembrance Day wreath at the foot of the National War Memorial in Ottawa; Robert Rae received that honour. And none was prouder than his son, Steve.

Before I left Tillsonburg, the night I met Spencer Wallington’s daughter, Betty Lou showed me the medallion she always wears around her neck – the Silver Cross, awarded the next of kin of a Canadian soldier killed on active duty. Only then, was her voice breaking slightly, her fingers trembling. “Always proud,” she said, “proud of his service.”

Please join me tonight (Thursday) at 7 at the Royal Canadian Legion, Branch 170 (109 Franklin Street) or on Nov. 9 at 7 p.m. at Slabtown Cider Co. (4559 Concession Road 6) to remember the forgotten of the forgotten.

Absolutely fascinated by your stories told last night on The Agenda; thanks.

I was told, as a youngster, that my father was the first person in Canada, after the telegraph operator, that the war (WW2) was over. I had just been born a couple of hours before this on May 7th, 1945. I’d be happy to tell the full story, if it’s of interest to you.