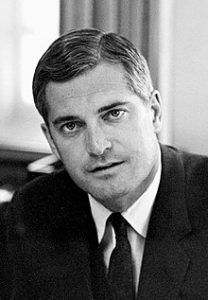

When they talk about brushes with fame, I consider a morning at Sidney Airport on Vancouver Island, among them. It happened in the early 2000s. I’d arrived for my flight to Toronto early. I’d gone through security and arrived at my gate, when there sat John Turner, the former prime minister of Canada, reading a newspaper and waiting for the same flight.

Never intimidated by celebrity and always attracted to political figures, I sat down near him and said something like, “I’ll bet, since your retirement, trips back East are a whole lot less stressful than when you were prime minister.”

“You’re absolutely right,” Turner said with a smile. He turned to me and added, “but they’re still awfully long.”

Born in the United Kingdom, John Napier Wyndham Turner became Canada’s fourth longest-lived prime minister (he died in 2020 at age 91), serving 8,326 days as a member of Parliament. He famously qualified for the 1948 Olympics in London, studied at Oxford University on a Rhodes Scholarship, danced with Princess Margaret during an official event in B.C., and got tongues wagging around the Commonwealth they were a couple.

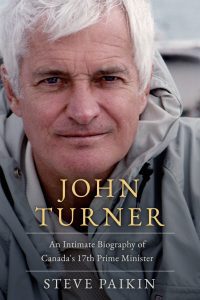

But as author Steve Paikin writes in John Turner: An Intimate Biography of Canada’s 17th Prime Minister, Turner “lived a life of consequence,” serving as opposition leader, finance minister, justice minister and one-time Bay Street rainmaker. Unlike my chance encounter in Sidney Airport, Paikin enjoyed frequent professional and social encounters with Turner, and after each, Paikin wrote, “he’d say ‘Stay in touch’ in just such a way that you knew he meant it. And so I did.’”

But as author Steve Paikin writes in John Turner: An Intimate Biography of Canada’s 17th Prime Minister, Turner “lived a life of consequence,” serving as opposition leader, finance minister, justice minister and one-time Bay Street rainmaker. Unlike my chance encounter in Sidney Airport, Paikin enjoyed frequent professional and social encounters with Turner, and after each, Paikin wrote, “he’d say ‘Stay in touch’ in just such a way that you knew he meant it. And so I did.’”

The resulting book – based on Paikin’s research and remembrances – offers unique and moving insight into a parliamentarian who amounted to much more than the mere 11 weeks he served as prime minister, the second shortest-serving prime minister in Canadian history.

Paikin reminds us how Turner seemed destined to accomplish great things, well before his term in Parliament. In particular, while practising law with the Montreal firm Stikeman Elliott, he took on the case of Mennonites from Alberta contesting their tax-exempt status.

The case was a hot potato, but Turner represented the case right up to the Supreme Court, where he won a unanimous decision. His peers, including up-and-coming lawyer Donald Johnston, “assumed Turner would one day be Prime Minister.”

I’ve read my share of political tomes on Canadian politics in the 1960s, but Paikin’s exploration of the 1968 Liberal leadership campaign rivals all. With unprecedented access given by the Turner family to the man’s private papers at Library and Archives Canada, Paikin reconstructs Turner’s passionate campaign as a reformer and voice for a new generation versus Pierre Trudeau’s cool intellectualism.

Then, as Paikin does so well, he recreates the delegate balloting at the convention – right down to the fourth round when Turner refuses to back either Robert Winters or Trudeau. “I’m going right to the end,” Turner says, conveying, in Paikin’s words, “the image of a guy who wasn’t a quitter.”

Many forget, though not biographer Paikin, that John Turner served in Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s cabinet for seven years (1968-1975). During his first four years in cabinet, the former lawyer worked as hard as he had to become party leader, only in the justice portfolio, strengthening the rights of individual defendants on trial, increasing the efficiency of the justice system, creating the Law Reform Commission, and upgrading professional qualifications of judges. As important, Justice Minister Turner guided his department through one of Canada’s darkest periods – the October Crisis of 1970.

Of course, Paikin recounts Turner’s famous 1984 leaders’ debate against Conservative leader Brian Mulroney. “I can beat Mulroney, debating the issues,” Turner told his Liberal campaign team. But on the issue of patronage, when Turner said, “I had no option,” Mulroney pounced, “You had an option, sir! You had an option to say no and you chose to say yes to the old attitudes.”

On Sept. 4, 1984, the Liberals were swept from power in a Tory landslide, and Turner resigned after just two months and 17 days as prime minister.

As biographer Steve Paikin points out in his analysis of John Turner’s post-political life, “In the United States former presidents are called ‘Mr. President’ for the rest of their lives. The tradition in Canada is to stop calling our heads of government by their titles.” Paikin adds that “there’s something levelling about holders of high office being treated more normally after their time in the spotlight.”

I agree. But on that morning 20 years ago when I met John Turner in the Sidney Airport and we’d finished our short conversation before the flight to Toronto, I remember signing off with, “Thank you, Mr. Prime Minister,” out of respect for the man’s service to Canada.