One day last summer, I shared a walk with several of my grandsons. They wondered about an empty storefront on Toronto Street. “What did it used to be?” they asked.

“Ballinger’s store used to be there,” I told them. “You could buy clothes and shoes and all sorts of dry goods there,” I said.

“What’s dry goods?” one of them asked.

“Just about everything you’d ever want to buy that’s not food,” I said.

“You mean like on the internet?”

Well, you can imagine where the conversation went after that.

The boys talked about buying video games, books, headphones, clothes and everything else online and having Amazon deliver purchases to their house a day or two later. Discussions such as these – in the 21st century – seem an awful long way from the days when shopping was an excursion, not click-and-enter on a keyboard, when customers interacted with expert salespeople, not anonymous corporations in Silicon Valley, and when one actually touched and tried something on before buying it.

I got to thinking about the radical changes in retail this week as I read news that Nordstrom was closing its operations in Canada. Launched in Canada in 2014, Nordstrom established 13 stores, and at the time of the closing announcement, employed about 2,500 people in this country.

And as its flagship store goes dark, I realize it’s closing in yet another tenuous retail platform – Toronto’s Eaton Centre mall – along a stretch of Yonge Street that for a century and a half functioned as the heart of retail in Canada, where the big three – T. Eaton Co., Robert Simpson Co. and the Hudson’s Bay Company duked it out for retail supremacy for over 100 years. Such stores led the marketplace for serving entire families, entire cities with everything they ever needed under one roof.

And not only could Eaton’s, Simpson’s and Bay shoppers buy anything and everything from around the world, so could customers enjoy such advances in people-moving as elevators and escalators. And even if they never bought a single dry good, any excursion in front of or behind its massive street-front display windows could be chalked up to an entertaining day of “window shopping.”

Shoppers in our own community enjoyed similar experiences – albeit mostly on a single floor – in the heydays of department store shopping. Beginning right after the Great War, William Hochberg operated Dominion Dry Goods store on the south side of Brock Street, west of Bascomb. His “Going Out of Business” sale sign stretched nearly half a block in 1961. Nick Homan stepped up and bought it a couple of years later.

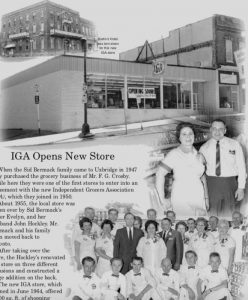

Downtown Uxbridge in those years also sported the newest concept in food shopping experiences in the 1950s, when Evelyn and John Hockley purchased the store at the corner of Toronto and Brock, completed an agreement with Independent Grocers Association, and opened the IGA “supermarket.”

“The new IGA store,” wrote J. Peter Hvidsten in his book Uxbridge: The Good Old Days, “offered 4,000 square feet of shopping space, with four 45-foot merchandising aisles and four full-automatic check-out counters. There was 36 feet of refrigerated self-service counter … and 36 feet of refrigerated space for produce.”

Like most thriving Ontario communities with one foot in urban development and the other in the farmyard, in the 1950s and ’60s, Uxbridge enjoyed all kinds of shopping options – the downtown Williamson car dealership, first-run movies at the original Roxy, a local creamery, the Co-op farm-goods store, the Mansion House Hotel and our very own Coca Cola bottling plant, which was among the first bottlers in Canada to begin producing and distributing “Fanta” sodas.

Department stores gave members of my family valuable employment during the Depression. After she’d graduated from a stenography college in New York City in the 1930s, my mother, Kay Barris, earned valuable family income as a sales clerk at Macy’s department store in Manhattan.

She remembered dressing with the best her wardrobe offered, because she was representing the store and serving the public every day. And that meant selling on her feet, wearing her stylish but debilitating high-heeled shoes, through every eight-hour shift. The bunions on her feet remained a vestige of her department-store career for the rest of her life.

I remember telling my grandsons about their great-grandmother’s experiences selling dry goods in a department store. They seemed suitably impressed by her work ethic and history, but kept reminding me that it’s sure a lot easier “buying stuff online.”

I guess when the world seems at your fingertips on a computer with turnaround service at our doorstop, saving the era of retail in a department store doesn’t have nearly the appeal.