The archivist at the museum had no idea it was there. In fact, when Jean-Phillippe Stienne applied for and landed the job as new archivist and collections manager of the museum, archives and art gallery in Nelson, B.C., back in 2017, he knew nothing about the explosive history buried beneath his new office.

“I came here because it’s a beautiful part of the world,” Steinne, 43, told me during a speaking stop I made in British Columbia last week. “I’d actually been working here a few years before I knew about the mystery under the museum.”

“I came here because it’s a beautiful part of the world,” Steinne, 43, told me during a speaking stop I made in British Columbia last week. “I’d actually been working here a few years before I knew about the mystery under the museum.”

When I asked what he was talking about, Stienne, or “J.P.” as everybody calls him, walked me out the front door of his museum (formerly the Nelson post office) and down a back alley to an adjacent building. He unlocked an exterior door, which revealed an inner door with a thick circular porthole window and a black-lettered sign that read, “Nelson’s Cold War Bunker.” Down several flights of concrete stairs, J.P. led me into an unexpected basement from a very different time.

In the early 1960s, the City of Nelson (600 km inland from Vancouver) issued a building permit to local contractor Louis Maglio on behalf of the federal government to excavate and construct a Zonal Emergency Measures Organization (EMO) shelter beneath the federal Gray Building on Vernon Street in Nelson.

The underground facility – a.k.a. “the bunker” – would provide shelter and a workplace for about 70 people deemed essential by Ottawa to keep civic affairs moving in the event of an atomic bomb attack. Contractor Maglio, who would later serve as mayor of Nelson, estimated a final cost of $57,000.

The entire operation, to build, service and maintain the bunker, however, was done in secret.

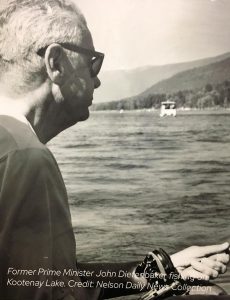

But why would then Prime Minister John Diefenbaker direct the construction of an emergency shelter in the wilds of the B.C. interior? There are several plausible scenarios.

In the 1950s and early ’60s, sabre rattling between the Soviet-led communist bloc countries and the U.S.-led West had triggered the Korean War, the Berlin Wall, the Cuban missile crisis and the proliferation of nuclear weapons on both sides. In the face of a potential “shooting match” between East and West, Diefenbaker authorized Project EASE (Experimental Army Signals Establishment), i.e. the construction of nearly 50 nuclear fallout shelters in the event of a nuclear attack. The largest facility – a 100,000-square-foot underground bunker at Carp, Ont., west of Ottawa – would keep 535 people alive for 30 days.

It’s no coincidence either that the Nelson bunker was also located near Trail, B.C., where zinc-mining firm Cominco was producing heavy water, a vital element in the development of nuclear weapons. That, of course, made the B.C. interior a potential wartime target.

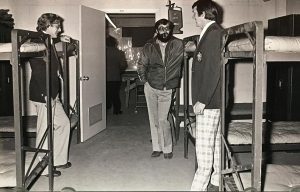

All of this history, J.P. Stienne and his museum colleagues have displayed on the walls of the original Nelson Cold War shelter. Visitors can see the original decontamination showers, communications room, fully stocked kitchen and dormitories that would keep civic officials alive and comfortable for weeks underground, just like shelter outside Ottawa.

But there was yet another possible explanation for locating the so-called “Diefenbunker” at Nelson:

“Prime Minister John Diefenbaker loved fishing on Kootenay Lake,” read one of the wall posters in the Nelson bunker. “If war broke out while he was on holiday, he would not have been far from a safe place to govern.”

As a kid in the 1950s, I remember our elementary school teachers showing us civil defence pamphlets and movies in the classroom. They instructed us to practise survival techniques: “Hide under a desk to protect yourself against flying objects. Bury your face in your arms,” the literature told us.

Then in 1962, when Soviets placed missiles on Cuban soil just a hundred miles from Miami, and the Americans responded by threatening to sink Russian ships en route to Cuba, we all thought the world was on the brink of thermonuclear war. That’s when all us kids wished our parents had taken things seriously and built air-raid shelters in our backyards.

As archivist J.P. Stienne led me back up the stairs out of the Nelson bunker last week, I asked him when the facility was finally closed.

“Well, as late as the 1980s, the bunker was visited by federal civil servants who checked the food supplies, the water and other services in the bunker,” Stienne told me.

In other words, even as the communist Soviet Union disintegrated and the Berlin Wall (symbol of the Cold War between East and West) tumbled down, Canadian officials still kept a protective eye on Nelson’s Cold War Bunker. Just in case.

Definitely in interesting story, one worth exploring.

Hello Ted Barris,

I just finished reading your Battle of the Atlantic and my only regret is that my dad isn’t alive to read it and, better yet, talk to me about it. What an amazingly great book! Dad – Harry Webster “Smitty” Smith – was in the Canadian Navy on corvettes and, I think, a couple destroyers as a radio operator throughout the war. He was also at the D-Day invasion. He left me with quite a few stories, an extensive photo album including scenes from aboard ships as well as leave in bombed-out London and dirigibles in the channel. I also have his code-book (with the lead-lined cover), Morse code key, a signal gun taken from a sunken ship (he carved the info into the stock), his hammock and kit-bag (big). (It’s getting to be time to part with these things to an archive somewhere). Dad was a “prairie boy at sea”, joining up in Calgary, where he grew up after his family had to leave their homestead in southern Manitoba after his dad (my grandfather) died in WWI at Vimy Ridge. Anyway, many thanks for your book. It really put the battle of the Atlantic and Canada’s role into perspective for me and crystalized a lot of things dad told me. I knew it was dangerous but I had no idea exactly how dangerous, nor how it was, in part, right on Canada’s doorstep.

Sincerely,

Shirleen Smith

Riondel BC (across Kootenay Lake from Nelson – and your story about the nuclear bunker)