Nobody told him to go looking for a wonder of the modern world. But about 30 years ago, when he moved from Calgary to Vancouver Island, model-train buff Ken Ortwein kept hearing about an architectural treasure not far from where he now lived.

He took his son and grandsons up the island on the Trans-Canada Highway, then into the remote Cowichan Valley. There, across a deep river gorge near Shawnigan Lake, he saw the Kinsol Trestle for the first time.

“I fell in love with the crazy thing,” he told a local news reporter. Then, as he noted in his diary, “I thought I ought to build a scale model of it. And so, it began.”

Standing about half as tall as Niagara Falls, 44 metres, and about the length of two football fields, nearly 200 metres, the Kinsol Trestle is the largest railway bridge in the British Commonwealth, among the tallest free-standing and timber rail trestles in the world.

At the beginning of the last century, when forestry industries gained a toehold on Vancouver Island, lumber companies envisioned a means of connecting the island’s massive old-growth forests with the port of Victoria. Canadian Northern Pacific Railway engineers planned an interior railway line with a span across the Koksilah River.

That span would be built beginning in the 19-teens near the King Solomon copper and silver mines, thus the abbreviated name – Kinsol Trestle. The trestle served regular passenger and industrial rail traffic for 60 years.

But even all of that transportation history wasn’t what motivated railroader Ortwein to build a model of it. “The whole thing intrigued me,” he said.

From its original construction between 1914 and 1920 and its subsequent upgrade in 1934, Ortwein discovered a structure deemed among the most sophisticated pieces of railway architecture of its day – a hybrid structure (of Douglas fir timbers) comprising eight parallel trusses, resting on concrete piers and supporting six decks of framed trestlework.

The spans on either side of the trusses consisted of 46 multi-decked timber bents (triangular vertical braces) to support the 614 feet of railway deck, including a seven-degree curve across the gorge.

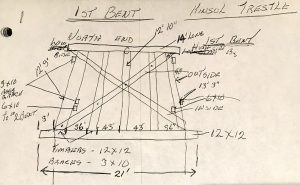

Last week, I had the opportunity to read through Ken Ortwein’s construction notes and diagrams. Armed with a 30-foot tape measure, a pen and a scribbler, Ortwein launched his model version of the historic trestle in 1994.

Every page of his scribbler contains sketches, measurements and memoranda for each one of the eight trusses and all 46 bents supporting the trestle. He chose to recreate the trestle on a 1:50 scale – a model 12 feet long and three feet high. While the actual Kinsol Trestle took four years to build, it took Ortwein even longer to build his version.

“I worked on the model for over six years,” he wrote in a journal. “Each and every piece of wood is cut on a table saw … each piece twice, and some three times (to get them right). I (cut) my own ties and laid the track. The cross-bracing pieces are put together with straight pins and glue. The bents with half-inch nails and glue. I loved every minute of it.”

My tour of the Shawnigan Lake Museum, last week, revealed that the actual trestle survived a number of setbacks, some of which nearly destroyed the historic piece of transportation architecture. The railway abandoned the trestle for ruin in 1979. Next, the provincial government acquired it for potential recreational purposes. Vandals twice burned its superstructure.

Eventually, the Cowichan Valley Regional District stepped up to raise millions of dollars to restore it and maintain it for hikers, cyclists, and equestrian activities. It’s now part of the Trans-Canada Trail.

I’ve often thought that the notion of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World (i.e. Roman Colosseum, Great Wall of China, Taj Mahal, etc.) needs a contemporary and even a Canadian makeover.

Not just into the 21st century, but to also include more modern marvels of human engineering – structures such as the Fogo Island Inn, Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic Biosphere at Expo 67, Province House in Prince Edward Island, Arthur Erickson’s Museum of Anthropology at UBC, and in Toronto the Sharpe Centre for Design.

Despite its remote location and some inclement weather that day on Vancouver Island, friends recently made sure that I saw the Kinsol Trestle. Not only did I walk the full length atop the trestle, but I also clambered down to the Koksilah River bank for a perspective from the trestle’s base. Impressive it must have been in 1920, as it is today.

But model railroader Ken Ortwein described its impact best: “It was the sheer mass of it!”