Seventeen years ago, a number of Canadian and American scientists set off on a unique voyage – sailing the Bellot Strait, a narrow channel in the Arctic Ocean that separates the most northerly point of North American mainland from Somerset Island in Canada’s Far North.

For the first time in history their vessel crossed the strait in October (when typically it would be frozen). One of the scientists on the trip in 2006 noted that Canadian Coast Guard officials aboard the ship all had the same reaction.

“They were collectively terrified,” explained Michael Byers then director of the Liu Institute for Global Issues at UBC. Terrified that the strait was entirely ice-free during the voyage, and therefore open to passage. In other words, about 1.2 million square kilometres of Arctic Ocean – Canada’s northern frontier – lay wide open to any ship of any nation at any time.

Today, when global warming has the polar ice cap melting as much ice as an area greater than the state of California every year, when the economic potential in the North remains so attractive, and when the planet’s three most powerful nations – the U.S., China and Russia – continue to sabre-rattle all around us, Canada’s Arctic frontier remains dangerously vulnerable. Or, given the presence of so-called spy balloons, some might suggest the North sits undefended.

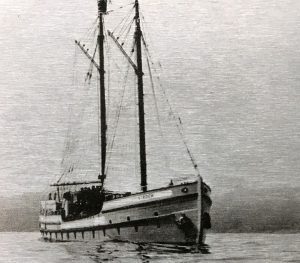

It wasn’t always that way. In 1928, the Burrard Dry Dock shipyards in North Vancouver constructed a 100-foot-long police schooner, named St. Roch. Based on the same design as Maud, Roald Amundsen’s exploration polar exploration ship, St. Roch’s hull was made of thick Douglas fir and Australian “ironbark” eucalyptus wood, to withstand the punishing pressure of Arctic ice.

She was commissioned in the service of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to patrol Canada’s 2,000-kilometre-long Arctic coastline. I walked aboard this historic vessel last week inside Vancouver’s Maritime Museum. Even sitting on dry land, I could hardly imagine such a small ship surviving Arctic sea conditions.

“She heaved and bucked like a bronco,” wrote her captain, Henry Larsen. And he was the only sea-going person on her crew.

Yet, during the Second World War, when Canada’s North first seemed at risk, St. Roch and her landlubber RCMP crew became the first vessel to transit the Northwest Passage from west to east and thus the first important symbol of Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic.

Using the Bellot Strait (the same one navigated originally by Amundsen in 1903) and warned by the Americans he was blocking U.S. access to international waters, Capt. Larsen sailed from Vancouver in June 1940 anyway. St. Roch wintered at Victoria Island, reaching Halifax in October 1942. Larsen received the Royal Geographical Society’s Patron’s Medal for his achievement.

Among her wartime crew, Constable Eugene Hadley was typical. Born in 1928 in Weyburn, Sask., about as far from the sea as one could imagine, Hadley took shorthand and typing at school, joined the RCMP and served at its crime lab. Nevertheless, in 1940 he joined St. Roch for that first Northwest Passage voyage.

One journal entry during the trip noted that Hadley “was so seasick that (he) just stands at the rail of the ship refusing to move.” Nevertheless, Hadley’s skill as a radio operator kept southern RCMP detachment offices in-the-know about St. Roch’s progress.

As I strolled about the ship’s decks, I spotted a brass weight shaped like a ship’s propeller on a rear deck. I asked one of the Maritime Museum interpreters for an explanation.

“It’s called a loch line,” Owen Stewart Jordan told me. “They used to toss the weight tied to a rope off the stern. The weight spun in the water and based on the rotation of the rope in the sailor’s hands, they could determine St. Roch’s speed. Kind of like a speedometer.”

I ventured into the ship’s forward crew’s quarters. Half a dozen men slept, washed and ate where today a two people might feel quite cramped and claustrophobic. “You become so familiar with everything about everybody in such close quarters,” Eugene Hadley wrote. And it was like that for two years, as St. Roch carefully navigated that Northwest Passage eastward. Hadley said the crewmen learned to occupy themselves reading, resting or playing cards.

When the world learned of St. Roch’s incredible passage, Larsen lauded the ship’s voyage of discovery, while de-emphasizing her mission to protect Canadian interests in the Arctic from the Americans and Soviets. Const. Hadley, while proud of being part of history, “swore (to a fellow crewman he’d) never go aboard a ship again as long as (he) lived.”

When the world learned of St. Roch’s incredible passage, Larsen lauded the ship’s voyage of discovery, while de-emphasizing her mission to protect Canadian interests in the Arctic from the Americans and Soviets. Const. Hadley, while proud of being part of history, “swore (to a fellow crewman he’d) never go aboard a ship again as long as (he) lived.”

I guess like sovereignty, there are limits to one’s constitution.