The festival began the way most events do these days in Canada. With respect. Last Thursday evening, the creative director of a festival in which I was participating, came to the microphone at the lectern, looked at the assembly of novelists, non-fiction writers, poets and all the other festival-goers. With appropriate sincerity and solemnity, she read the local land acknowledgement.

“We acknowledge that we are on Treaty 4 land,” she said, “encompassing the lands of the Cree, Saulteaux, Dakota, Nakota, Lakota and on the homeland of the Métis Nation.”

That’s the way the 27th edition of the Saskatchewan Festival of Words began in Moose Jaw, last week. Many of the 30-plus writers contributing to the four-day festival arrived in time for the opening ceremonies, including Bob McDonald (host of CBC Radio’s Quirks & Quarks), Suzette Mayr (2022 Giller Prize winner), Ali Hassan (host of Laugh Out Loud and Canada Reads), Michelle Good (Governor General’s Award winner).

As one of the non-fiction participants, I was asked to offer a story or two as a tease to my later book presentations during the festival. But for the first time – in all the times I’ve listened to land acknowledgements at public events in the past few years – I wondered what was wrong with them?

Yes, they tell me which First Nations were displaced, from where they were displaced, and what misguided principles inflicted the displacement. But that’s all. These land acknowledgments – however respectful and appropriate they may be – have become cliché.

To me they seem a bit like singing O Canada before NHL games, or saying grace before a meal. Land acknowledgements are a formality. They’re an offering in lieu of loss and out of respect. But they really should be more than symbolic.

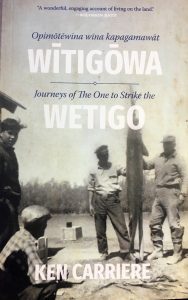

Remarkably, just minutes after that land acknowledgement at the Moose Jaw festival, I discovered one way to make these important gestures more meaningful. One of my fellow author/presenters, a man named Ken Carriere, stepped to the microphone. He held up a copy of his memoir, Journeys of The One to Strike the Wetigo, a book about his life as a Swampy Cree trapper, fisher, guide and educator from the Saskatchewan River delta.

Remarkably, just minutes after that land acknowledgement at the Moose Jaw festival, I discovered one way to make these important gestures more meaningful. One of my fellow author/presenters, a man named Ken Carriere, stepped to the microphone. He held up a copy of his memoir, Journeys of The One to Strike the Wetigo, a book about his life as a Swampy Cree trapper, fisher, guide and educator from the Saskatchewan River delta.

The front cover of his memoir shows an historic moment in Carriere’s life, in the early 1960s, when his father Pierre landed a 160-pound sturgeon fish in the Saskatchewan River Delta. As well as the gigantic fish (as tall as the fisher who caught it), the photo includes Ken’s brother, who actually chased down the person to photograph the record-breaking sturgeon.

“The picture also shows my brother Franklin, who’d been forced to cut his long hair short by the Indian Residential School he attended,” Ken said. “It was a symbol of the racism our people suffered.”

While I’ve always known generally about the systemic racism of Canada’s residential schools, I had little understanding of such specific abuse inflicted on young Franklin Carriere (and thousands like him). It occurred to me that’s the sort of acknowledgement Canadians should hear, see and understand before experiencing a hockey game, church service, government session or artists’ festival.

In other words, Canadians need not only know about the displacement of Indigenous Peoples from their land, but that displacement had personal and tragic consequences. And if we are ever going to reconcile abuses committed by our predecessors, we need to recognize their individual and universal impact.

As it turned out, Ken Carriere gave me more than the essence of truth and reconciliation. After the opening ceremonies at the Festival of Words the other night, my wife and I joined Ken for supper. He shared more of his experiences working as a geologist in Saskatchewan’s mineral-rich north. He told us stories of his family’s connection to outfitting, hunting, fur trapping and transport on the Saskatchewan River going back a hundred years.

It suddenly occurred to me that Ken’s and my paths might well have crossed when I was researching my first book on early prairie steam navigation 50 years ago.

“Did you ever know a man named Bill McKenzie?” I asked.

“Steamboat Bill McKenzie?” he said. “He was my uncle.”

“Your uncle took me to the riverside in 1973,” I told him. “He showed me how he read the sandbars, snags and currents of the Saskatchewan River, and probably saved lives piloting steamboats (like S.S. Saskatchewan) safely up and downriver.”

In that moment, I realized that reconciling our relationship with First Nations goes much deeper than land acknowledgement. At a time when we desperately need to understand global problems, undo our misuse of the environment and reconcile human relationships, answers may be as close as sharing with our most experienced neighbours.