I remember the day I learned what I would do the rest of my life. I received a message from a historical society in the U.S. It described an overseas tour planned for that fall of 2017. Participants would fly to Europe and retrace the wartime steps of Gen. George Patton’s 94th Infantry Division – to halt the Nazi breakout toward Antwerp – a.k.a. the Battle of the Bulge.

That’s where my father served as a medic in the U.S. Army. I needed to experience that tour. But that meant I’d have to quit my position as a journalism professor at Centennial College in Toronto.

“You’ll have to speak to our retirement specialist,” the dean of Centennial’s communication school told me.

I met the specialist in his office a few days later.

“So…” he enthused, “are you ready for retirement?”

“You don’t know anything about me,” I said. “I’m not retiring. I’m just going back to where I came from.”

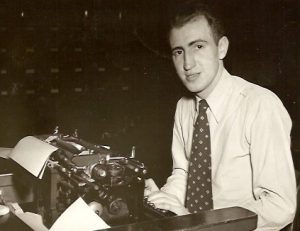

For the 30-plus years before I was invited to teach at Centennial in 1999, I had worked as a freelance writer and broadcaster all over Canada. Today they call it the “gig economy,” or the segment of the service economy based on flexible, temporary or freelance jobs. Observers of the gig economy make it seem as if they invented it during the pandemic, when in fact writers and broadcasters, such as my father, have practised it for decades.

My point it that when I gave up my short tenure teaching at the college, I realized I could return to a life of writing and broadcasting what I wished when I wished. It was my form of semi-retirement.

I’ve been reading a feature story written by Cathrin Bradbury in Walrus magazine, called “The End of Retirement.” She retired from the CBC about a year ago, but had worked over the previous 40 years as a journalist at Maclean’s and the Toronto Star, etc. She wrote that she wasn’t sad to leave the grind of daily deadlines and punishing news cycles of mayhem, death and destruction.

I’ve been reading a feature story written by Cathrin Bradbury in Walrus magazine, called “The End of Retirement.” She retired from the CBC about a year ago, but had worked over the previous 40 years as a journalist at Maclean’s and the Toronto Star, etc. She wrote that she wasn’t sad to leave the grind of daily deadlines and punishing news cycles of mayhem, death and destruction.

But with 12 months away from work, she had two words of advice for friends considering the same path: “Don’t retire.”

In her research, Bradbury learned that about a thousand people are retiring in Canada every day; in other words, about one million Canadians are currently living in retirement. When she looked at her own situation contributing to company and government pension plans, however, she reached a startling conclusion.

“There’s not enough gold in my golden years,” she told her financial adviser. “You’re not alone,” he told her, and then explained that thanks to inflating rents, rising-interest mortages and growing grocery and fuel costs, Canadians are suffering. Bradbury quoted a BMO study released earlier this year. It summarized that Canadians today think they need $1.7 million to retire, a figure that’s risen 20 per cent since the pandemic (from $1.4 million).

Her story grew even darker when she recounted watching a Japanese movie, Plan 75, which paints a bleak future in which $1,000 is offered to the elderly to terminate their own lives, thus taking the burden off society having to support them – a modern day sci-fi edition of the Kamikaze philosophy.

I suspect there are more of you (reading my Barris Beat column) who are retired or semi-retired than those working full-time, flat out and fighting to keep the wolf from the door. However, if I could, I’d wish all those younger readers to accept my unprofessional advice. Don’t retire!

Instead, plan to work in a field that is regular, but with flexible hours. Find something with little or no stressful responsibility. Most important, make sure it’s something you enjoy but that also challenges you mentally and physically. Too many of my friends couldn’t wait to retire. And when they did, they found themselves short of sufficient discretionary cash, bored with little or nothing to do, or worse, they fell ill in their idleness and died prematurely.

By the way, that trip to retrace my father’s steps in the Battle of the Bulge that forced me to retire from teaching in 2017? By coincidence, I actually found the place in Germany where Sergeant Alex Barris set up a first-aid post, saved dozens of lives that winter of 1945, and was awarded a Bronze Star for valour.

For me, a lifelong writer, getting the story is a perfect semi-retirement job. That’s what my father did. Back in 2003, Alex was 81 and writing a manuscript for his 11th book when he suffered a stroke. It led to his death, but as they say, “He died with his boots on.”