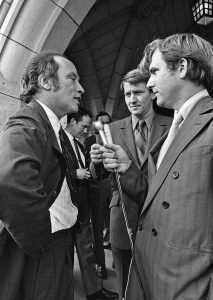

That October, the country was on the verge of civil war. At least that’s what it felt like. A Quebec cabinet minister had been murdered by the FLQ (Le Front de libération du Québec). A British trade official remained kidnapped. The then prime minister had introduced the War Measures Act to ferret out FLQ members and arrest those responsible.

As a senior student of then Ryerson’s Radio and TV Arts program and thinking only about getting the story on the air, I sat down in a radio studio at CJRT FM in Toronto and interviewed four students of Loyola College who’d been questioned in a Montreal dragnet just days before.

“My guests are John Welsh, Alan Saig, Joe Sagantic and John McKay,” I began. “Tell us how all this affected you.”

And they did. It was Oct. 28, 1970, the height of the October Crisis. As they spoke, I kept thinking, “What would the radio listeners on my all-night radio broadcast want to know? How frightening was arrest without habeas corpus (right to a trial)? What did my guests think was happening to the country?” What I hadn’t considered, was that having them on the air was a violation of that same War Measures Act.

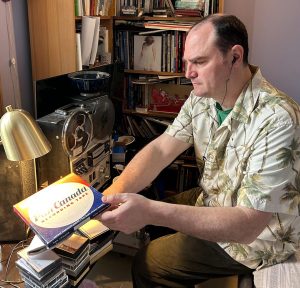

I’d nearly forgotten about that interview recorded 53 years ago. Except that my nephew, Jesse Doig, visiting from Saskatoon this week, has spent the week poking through my library of audio tape, listening to some of my old interviews and documentaries to digitize them.

My makeshift archives – in a dark, dry corner under the garage – contain hundreds of hours of reel-to-reel tapes and cassettes of radio material I assembled for broadcast between the mid-1960s and the 1990s.

Among the oldie goldies that have excited my visiting nephew is an interview I conducted in Edmonton with Hollywood actor Norman Fell, probably best known for his role as landlord Mr. Roper in the TV sitcom Three’s Company in the late 1970s.

Of all the memorable comments in such interviews, one that Fell shared has stayed with me. I recalled asking him what aspects of performance he found the most challenging.

“People think comedic actors are standup comics. It was the script writers who created the humour. We just lifted it off the page. And, by the way,” he added, “thanks for not asking me to be funny.”

Then, there is the radio script (we’re still looking for the actual tape) of a documentary my then collaborator, Ross Perigoe, and I produced for CBC Radio. Perigoe and I were still learning about radio but pitched some ideas to producers of a network show called Action Set.

We’d found experts in 1970 to talk about a looming environmental problem – noise pollution. To emphasize the point, Perigoe and I dramatized the perils of noise by taking listeners graveside to history’s first fatality (supposedly) due to excessive noise. I later shot a 60-second public service announcement of the script. It features the clergyman presiding over the burial.

As he finishes the eulogy to “the world’s first-ever victim of noise pollution,” the city noise around him drowns out his words. We found the film, the script and the White Owl Conservation Award that the PSA earned among the boxes, cases and files in my basement archives.

It occurred to me this week, as I watched my nephew load up the reel-to-reel tape deck and cassette playback machine for his digitizing of the content, that I was experiencing a rare phenomenon. Most moments of note today are not recorded the way we used to do it – for archival purposes.

While social media have become ubiquitous, I suspect very little is ever isolated, catalogued and stored with any more than instant gratification in mind. Most media, like the photos and video on your cellphone are captured quickly and haphazardly.

Sure, you can Google or YouTube search for highlights, but rarely are those pieces of history catalogued, contextualized or reviewed for anything other than instant gratification and out-of-context exposure. Somehow the respect for what actually happened has become secondary to how quickly I can source it, play it and then forget about it.

As for that interview I conducted on CJRT 53 years ago? Was I ever prosecuted for violating the War Measures Act? No. I was a practising radio show host. I was live on the air from midnight to dawn (the graveyard shift) on an October night in 1970. CJRT was considered, in part, a student radio station.

And it was the 1970s. Anything could and did happen. However, the truth is, probably very few people – maybe nobody – ever heard the interview. Nobody except for me and now, my nostalgia-inspired nephew listening and remembering what really happened.

Great article! 😊