It was July 1, back in 1966. I was a teenager working for tuition money at my uncle’s restaurant in Baltimore. I was wearing a T-shirt with the red Maple Leaf flag on it (it had become the symbol on our national flag the year before) and a customer at that Double-T Diner in Maryland asked me, “How come you’re wearing that red Maple Leaf on your shirt?”

“I’m Canadian. It’s Canada Day, our national holiday,” I said, “kind of like your July 4.”

He nodded as if he understood, but I quickly realized he didn’t. In my moment of pride, however, I thought I’d drive the point home. I tried to explain parliamentary democracy, that Lorne Greene (a.k.a Pa Cartwright on TV’s Bonanza) was actually Canadian, why (back then) in Ontario we couldn’t buy beer on Sundays, and universal medicare.

It was a waste of time. He wasn’t interested. And even my best attempts couldn’t make my Canadianism equal to his love of The Star-Spangled Banner, four downs in football or his belief that the U.S. had won the War of 1812.

I grew up partly in the United States. I say “partly” because almost all of my relatives either were or are Americans. After my parents – both New Yorkers – married in 1948, they moved to Toronto where my dad had landed a job with the Globe and Mail.

Because our parents had American roots and we were born in Canada, my sister and I had the option of dual citizenship, but neither of us ever pursued it. We always thought, “Why consider becoming specifically American, when Americans seem pretty much the same as Canadians?”

That was then. This is now.

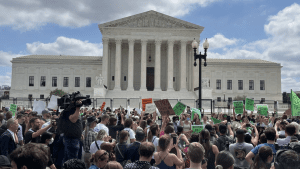

It’s been two years since the U.S. Supreme Court threw out 50 years of precedent, overruling Roe versus Wade. Following the decision (which essentially handed women’s control over their own bodies back to U.S. state legislatures), nearly 22 million women of reproductive age – or one in three women in the U.S. – have found themselves living in states where abortion is unavailable or severely restricted.

The Center for American Progress reported in 2022 alone, that state legislators introduced 563 provisions to restrict access to abortion and 50 of those were signed into law the same year.

Then, this week in a historic 6-3 ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court’s conservative majority (including three justices appointed by former president Donald Trump) ruled for the first time that former presidents have broad immunity from prosecution.

The decision, which current President Joe Biden described as “a dangerous precedent,” in effect puts those actions deemed “official” by any future U.S. president above the law.

No such provision exists for Canadian prime ministers. And while we do not have the same impeachment procedures they do in the U.S. congressional system, parliamentary committees and federal policing agencies have challenged federal leaders’ activities with effect – Jean Chretien’s sponsorship scandal and Brian Mulroney’s Airbus kickbacks scandal to name two.

Then, there are our now differing views on borders. Some years ago, a Nanos poll noted that “Canadians are more interested in reducing the obstacles to crossing the (U.S.-Canadian) border,” particularly as regards assisting refugees. Meanwhile, Americans “care more whether we are a part of an international coalition to fight terror.”

Meanwhile, the looming U.S. election pits two presidential candidates and their two polarized political parties farther from any form of international cooperation on borders with their neighbours. Back in 2014, Nik Nanos of the research firm conducting the poll described U.S.-Canada relations as “cordial yet dysfunctional.”

Meanwhile, the looming U.S. election pits two presidential candidates and their two polarized political parties farther from any form of international cooperation on borders with their neighbours. Back in 2014, Nik Nanos of the research firm conducting the poll described U.S.-Canada relations as “cordial yet dysfunctional.”

I recently tripped over a box in the corner of my office. It contains a coffee-table-sized book of photographs and quotations from Canadians and Americans living along our international border. The book is titled Entre Amis / Between Friends and celebrates “the longest undefended international border in the world.”

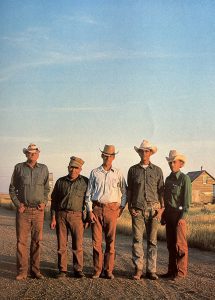

One of the spreads in the book that I’ve always considered prophetic, shows a group of farmers near Manyberries, Alta., not far from the Montana border. The photo caption quotes former Canadian prime minister John Diefenbaker: “Our peoples are North Americans,” it reads. “We are children of our geography, products of the same hopes, faith and dreams.”

One of the spreads in the book that I’ve always considered prophetic, shows a group of farmers near Manyberries, Alta., not far from the Montana border. The photo caption quotes former Canadian prime minister John Diefenbaker: “Our peoples are North Americans,” it reads. “We are children of our geography, products of the same hopes, faith and dreams.”

I fear Mr. Diefenbaker’s idealistic view of Canadians and Americans sharing those aspirations has faded continuously since the book was published in 1976. Our differences today consist less and less about four downs versus three, the different ways we pronounce “about,” or saluting maple leaves versus stars and stripes.

Today – on July 4 their Independence Day – I sense our vastly different perspectives on women’s rights, maintaining borders and legal immunity for our leaders, have set us on two divergent paths.

Hi Ted,

Seeing the cover of the book, “Between Friends,” spiralled me back in time. It was always on an end table in our living room, along with a hard cover collection of New Yorker cartoons, and then the magazines themselves. Your father and mine share those New York roots, and also having been brought up to Canada for work. Dad died in 2004, and while I miss him terribly, I think the garbage behaviour by supposedly functioning adults south of the border would have broken his heart if he were still alive; I know it’s breaking mine. There is an almost visceral streak of meanness running through the collective in that space where empathy used to live, where it belonged. I hope that as Canadians, we can take advantage of the opportunity to address hate at the roots, unworthy hate, inchoate hate flung as if it’s the new “in thing,” and guide the energy behind it better into thoughtful conversation, toward acknowledgement of personhood as sacred enough in just that to warrant care and consideration.

It seems the graciousness is getting beat out of the idea of leadership, replaced by juvenile grasping, taking. It’s clearly evident here in our own province, and seems to be threatening the country as a whole, but we can stop it. I’m a firm believer in the power of conversation; Be curious. Ask questions. Find common ground. And don’t say, “Well, nothing we can do about it.” We are responsible to each other, and to dismiss tending our potential is what will trip us in the end. I’m still gobsmacked about the state of the planet, but I think it’s because I love this planet, this world that after I throw up my hands in daily despair, I regroup and try again.