I’ve flown into Heathrow, the city of London’s major civilian airport, dozens of times – seeing a sky full of jetliners lined up to land at Europe’s largest commercial airport. But not until I met Torontonian Dorothy Firth, who lived there during the Second World War, had I ever imagined what the skies over that city might have looked like during a period known as “the Blitz.”

“It was always a nasty sound and a horrible feeling when the air-raid sirens went off,” she told me when I met her a few years ago, “because you never knew how fast the German (bombers) were coming.”

Until on Sept. 7, 1940, when Adolf Hitler gave his wartime air force orders to bomb London’s eight million residents into submission, the Luftwaffe had attacked only military targets in England; since July 10 (when the period known as the Battle of Britain began) German bombers had almost daily bombed and strafed Royal Air Force bases, coastal radar towers, aircraft manufacturing plants and London’s east-end industrial docks.

But following reprisal attacks by both sides on each other’s capital cities (London and Berlin) in late August, the gloves were off; Hitler told his generals and the Nazi party faithful that Germany was now engaged in “totaler Krieg” (total war) and that his country’s survival was at stake. So too was the survival of Western civilization. Dorothy Firth included.

“If things had been different in 1940, I’d have gone to university,” she told me. “But the war changed all that. You volunteered for duty wherever you were needed.” Almost immediately her days were filled with service in a host of capacities. Early each morning, she boarded a commuter train for downtown London where she worked as a clerk from 8 to 3 at Barclay’s Bank.

Next, she joined a canteen crew at London’s Waterloo train station dispensing hot meals, buns and tea to soldiers heading to military installations all over the U.K. At 5 p.m. she was on the commuter train back to her home in Richmond-Surrey to join an amateur song-and-dance troupe entertaining men at a nearby anti-aircraft battery.

Then, after dark, when German nighttime bombings began, she arrived at the local fire station to be prepared to snuff out German incendiary bombs.

“They came raining down like water,” she remembered, “like in a shower and they could start a fire anywhere. Of course, they were aiming for houses.”

On Sept. 7, German bombers dropped 330 tons of high explosives and over 13,000 incendiaries on London, each (burning at upwards of 4,500 degrees Fahrenheit) designed to burst into flames on contact with warehouses, fuel tanks, chemical plants, railway yards and entire residential neighbourhoods; 448 London civilians died that first night of the Blitz.

Those volunteer firefighters like Dorothy Firth were called “fire watchers,” whose job was to attempt extinguishing incendiaries wherever they landed. When I asked her what training and equipment she received to battle such lethal explosives, she first described the fire watcher’s issue uniform.

“The blue serge uniform was dreadful to wear. It was rough like contract carpeting. White shirt, tin helmet, gasmask, lisle stockings and black shoes.”

When I persisted about her firefighting gear, she said the fire hall gave her a bucket of sand, a shovel and a stirrup pump. That’s all.

The earliest days of the Blitz registered some of the highest fatality statistics. Air raid casualties in London climbed to their highest in September 1940, with 6,954 killed and 10,615 injured that first month. British songstress Vera Lynn, whom I first met in 1995, captured the aftermath of the daily bombings in a memoir.

She noted that “underfoot, the streets were frosted with millions of fragments of broken glass. After a raid, the nostrils were assailed by the acrid smell of a bombed-out street, an unforgettable mixture of dust, smoke, charred timber and escaping gas – the smell of death itself.”

She added that bomb blasts could “mangle the bodies of victims or capriciously leave a human being unhurt but stripped naked.”

For days after I interviewed Dorothy Firth in 2022, I kept imagining her – for the 57 days of the Blitz – fighting thousands of incendiaries with a bucket of sand, a shovel and a puny stirrup pump, the kind we used to fill our bicycle tires with air.

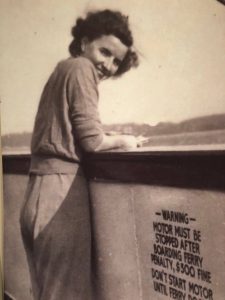

Toward the end of the war, Dorothy Firth met Canadian tank commander George Marshall, married and in 1946 immigrated to Canada as a war bride. She turned 102 in August. I figure if she could survive the Battle of Britain and Blitz as a fire watcher, by comparison, handling a century of life must be a piece of cake.