Sometimes politicians in Canada and the U.S. have described the economic struggles between our two countries as trade wars. More recently, observers on both sides of the border have recognized international tariffs as a form of economic erosion.

But if you think current trade hostilities across the 49th parallel are new, nothing could be further from the truth. A newspaper published in St. Paul, Minn., once encouraged American mercantilists to invade Canada and they were offered money as an incentive to do it.

“The St. Paul Chamber of Commerce will award a cash prize to the first enterprise to establish commerce in the British Northwest Territory,” reported the newspaper. “One thousand dollars to the first to arrive.”

The paper was published in October of 1858. The objective of the competition was to establish a business enterprise in what is now Manitoba, but which – since 1670 – had been Britain’s private domain for harvesting beaver pelts and all other resource riches of Prince Rupert’s Land.

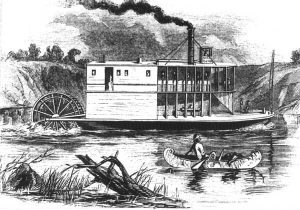

Then, in May 1859, a New York real estate broker named Anson Northup successfully navigated an American-built steamboat down the Red River to the British settlement of Fort Garry, later Winnipeg. For the first time since the War of 1812, Americans established a border-busting beachhead in British territory.

They called it “Manifest Destiny,” the notion that white Americans were divinely ordained to settle the entire North American continent. What’s more, with 100,000 U.S. federal troops located in the American Midwest, they had the clout to transform what was potentially the Canadian West into U.S. states. Sound familiar?

This was, in 21st-century terms, “an existential threat to Canada.”

And it gets even more interesting. Do you know who came to the rescue for Canada, immediately after Northup planted the U.S. stars and stripes on a Winnipeg dock 166 years ago? Not Britain. Not the Mounties nor the Canadian militia. Not even Sir John A. Macdonald and Empire Loyalists preparing Confederation talks in Charlottetown and Quebec in the 1860s.

No, the figurative cavalry to the rescue of Canadian sovereignty west of Lake Superior were a bunch of steamboat captains employed by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). Yes, the same organization that gave us those iconic Hudson Bay blankets, Bay Days and 96 stores across Canada that are all about to close their doors forever.

You will never have heard of them, but Norman Kittson, a fur trader from Quebec; William Robinson, a railway navvy from Quebec; Peter McArthur, a cabinet maker from Scotland; and James C. Burbank, a stagecoach company operator from Vermont, should probably be recognized as unofficial fathers of Canadian confederation.

As an illustration, with American steamboats suddenly following Northup’s lead – racing across the border and setting up shop in Fort Garry – James Burbank (with the Hudson’s Bay Company as his silent partner and backer) bought and refurbished a steamer, S.S. International, and began out-manoeuvring, out-selling and out-running the Americans on the Red River.

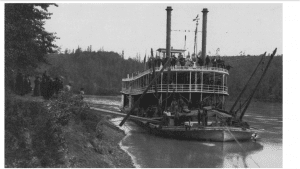

By the 1870s, races between American and HBC steamboats – races to get to Winnipeg before the competition – were typical. Once in May 1873, in order to arrive at Fort Garry, Manitoba, first, the International’s captain, Chauncey Griggs, “made a bold strike, and very coolly turned the flat-bottomed steamboat out of the bed of the river onto flooded prairie thereby reducing the distance and time reaching port.”

Shipping freight such as furs, flour and dry goods, kept American mercantilists at bay initially. Eventually HBC steamboats, 200 feet long and capable of speeds 4 to 6 knots, also began carrying immigrants by the thousands to the Canadian prairies.

“The S.S. North West, nicknamed ‘Greyhound of the Saskatchewan River,’ bragged that she could deliver passengers from Prince Albert to Edmonton in less than a week.”

American Manifest Destiny north of the 49th disappeared, and the four original eastern provinces absorbed Manitoba (1870), British Columbia (1871), and finally Saskatchewan and Alberta in 1905. Canadian Confederation now stretched from Atlantic to Pacific, in large part because of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

In 1995, Anne Murray fronted a commercial campaign for the Hudson’s Bay Company on TV and radio. In it she modestly noted the longevity of her own career as a successful singer and songwriter in Canada. “But after 325 years,” she went on, “nothing has the staying power of the Hudson’s Bay Company.”

In 2025, it seems, with yet another existential threat to our country – Donald Trump’s illegal tariffs and disregard for the treaty-signed existence of the 49th parallel – we are in need of staying power perhaps greater than a national department store.

We need the strength of ingenuity and resolve like those prairie steamboat captains.